The groundhog gets the spotlight, or at least the shadow, to itself on Feb. 2. The turkey becomes the ill-fated centerpiece of every fourth Thursday in November. The reindeer takes flight on Dec. 25.

But Oct. 31? Halloween belongs to the bat, the wolf and, increasingly, the spider. In fact, arachnologists and arachnid-lovers have staked a claim to the entire month of October, rebranding it as “Arachtober” ever since a couple of spider-fond photographers began exchanging their favorite shots online back in October 2007.

Thanks to Eileen Hebets, Nebraska’s resident arachnologist and Charles Bessey Professor of biological sciences, arachnids are even getting their due beyond the haunted confines of the year’s 10th month. In August, Hebets tweeted her appreciation for the way that Trey Smith, son of actor Will, safely removed a tarantula that found its way into the Smith’s home. Hours later, she was informing CNN that “most tarantulas are actually not dangerous at all.”

Need tips on safe & effective #tarantula removal? #WillSmith and his poised son score a perfect 10 according to this #arachnologist (@UNLsbs @unlcas)!

Thanks for a fun interview @NICKI_BR0WN @CNN #JeanneMoohttps://t.co/h6nliK3Q5K— Dr. Eileen Hebets (she/her) (@hebets_lab) August 23, 2022

When she’s not acting as an ambassador of the eight-legged, Hebets and her Husker colleagues are often busy studying spiders and the other 10 orders of arachnids. Here’s a roundup and rundown of the latest discoveries from Nebraska U.

Arachno-media

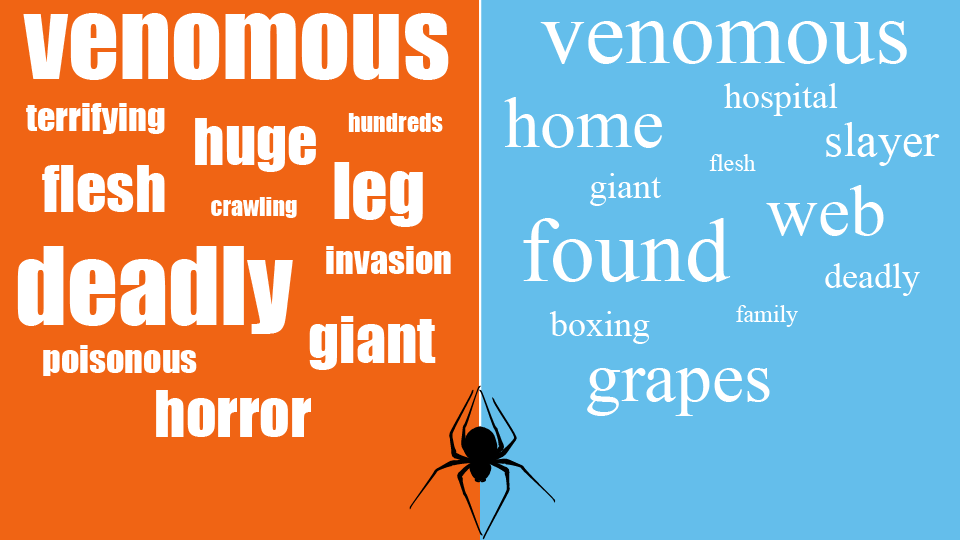

Hebets spoke with CNN as part of an ongoing effort to defang the many myths that have harassed arachnids, whose reputation belies the fact that fewer than five of every 1,000 species pose any health threat to people. One of her doctoral advisees, Laura Segura Hernández, recently contributed to a study that helped quantify how some media outlets might be perpetuating those myths.

Segura Hernández was among 65 researchers who compiled and analyzed more than 5,000 news articles written about human-spider encounters during the 2010s. The team judged 43% of the stories as sensationalistic, with many of those articles featuring stereotypically negative language such as “creepy crawly” and “nightmare.” Fewer than one in five stories consulted an expert. Probably as a result, 47% contained at least one factual error about spiders.

Mixed signals

Males of the wolf spider species Schizocosa stridulans have earned a reputation for courting females with a percussive performance worthy of a stage, unleashing a combination of movement and sound that can last up to 45 minutes.

After studying 44 such performances, Hebets and recent doctoral graduate Noori Choi concluded that the difference between getting rejected and getting lucky might come down to whether a male sticks with his routine or mixes up the status quo. The nine S. stridulans males that managed to mate produced more complicated vibratory signals — the musical equivalent of improvising and changing up time signatures — than did the 35 males that were turned down, the team found. And the successful males seemed to further ratchet up that complexity when courting heavier females, which tend to birth larger, healthier clusters of spiderlings.

Why would females prefer the complex signals? Though the males who produced them were no larger than peers who played the usual hits, the “vigor and skill” required to conjure that complexity could be traits that females prize for their offspring, Hebets said. It’s also possible that female wolf spiders, like their human counterparts, just get bored with the same old, same old.

“There are a lot of studies that show that animals prefer novelty, in some capacity,” Hebets said. “Increasing complexity, especially through time, you could almost think of as novelty — the males constantly changing things up to keep the females’ interest.”

Hidden in plain sound

Research on another wolf spider species, Schizocosa retrorsa, found that males attracted females just as often while standing in pitch darkness, and on granite — conditions that nullified the visual spectacle of waving a leg and the vibrations yielded by hammering it to the ground. Maybe, arachnologists thought, that male leg-waving was also communicating via near-field sound: stirring up air particles that then tickled sensory hairs on a female’s own legs.

To test that hypothesis, doctoral candidate Pallabi Kundu and colleagues ran experiments that retained the darkness and granite while adding white noise that could animate air particles enough to disrupt any near-field sound employed by the males. In two experiments, 21 of the 40 males successfully courted a female without the white noise, whereas only five of 40 did so when contending with that noise. Males in the latter condition also waved their legs less often, suggesting less of a willingness to invest energy when facing longer odds of success.

Feeling the heat

As average temperatures rise around the world, ecologists are investigating whether and how global warming might influence predator-prey dynamics. Nebraska’s John DeLong, Stella Uiterwaal and Alondra Magallanes turned to yet another species of wolf spider, Schizocosa saltatrix, for the sake of exploring those questions.

The Husker trio placed each of 60 S. saltatrix spiders inside a petri dish containing between three and 20 midges, or tiny flies, commonly eaten by those spiders. Those petri dishes sat atop heating pads set to one of four temperature settings, from the low 70s Fahrenheit up through the high 90s. S. saltatrix spiders killed and consumed the most midges at around 85 degrees, which also happens to be roughly the highest temperature that the nocturnal species encounters while hunting in the wild.

The study suggests that predators foraging at night, as most spider species do, may consume more prey in tandem with global warming. Animals that hunt by day, meanwhile, could potentially kill and eat less as temperatures surpass certain thresholds.