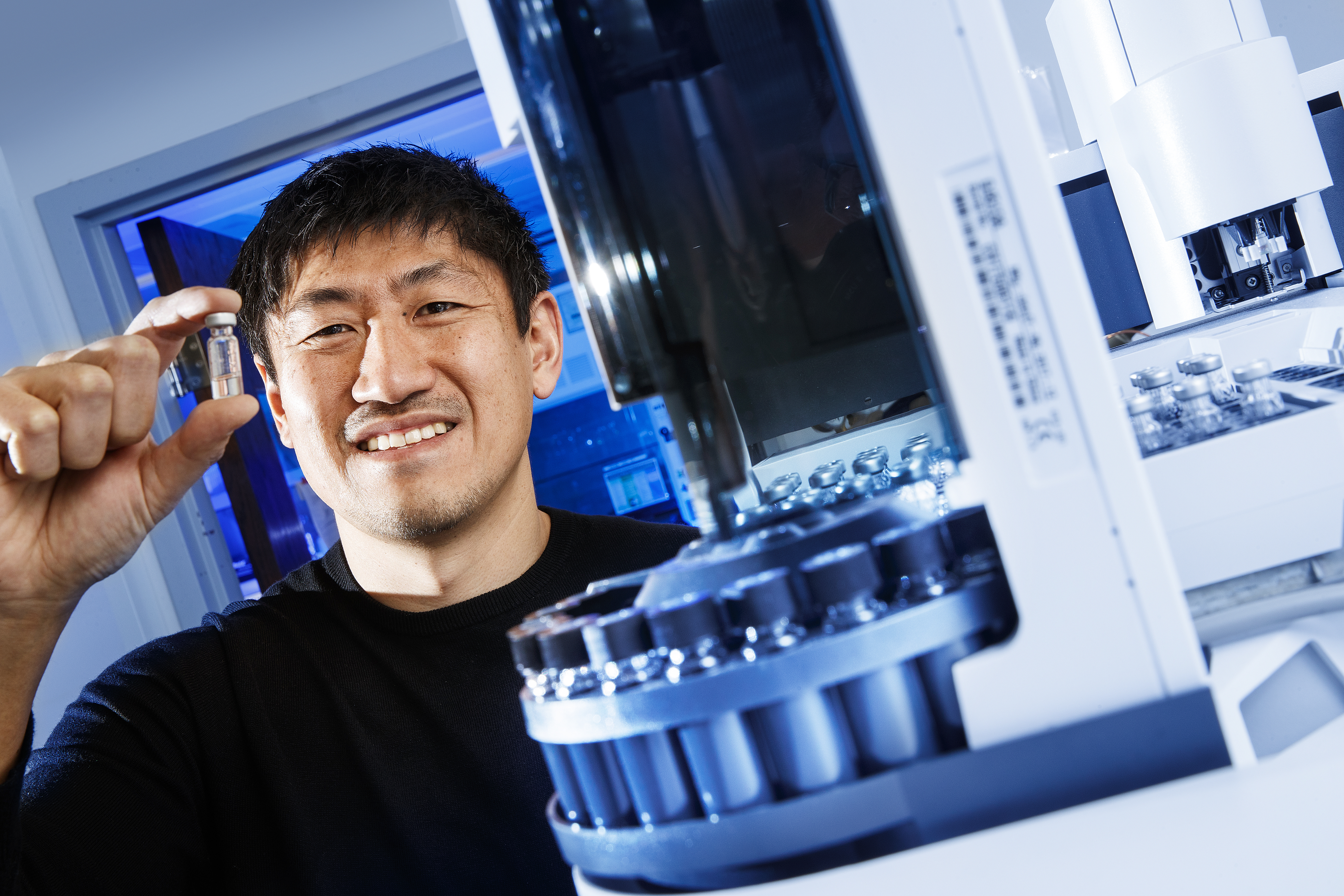

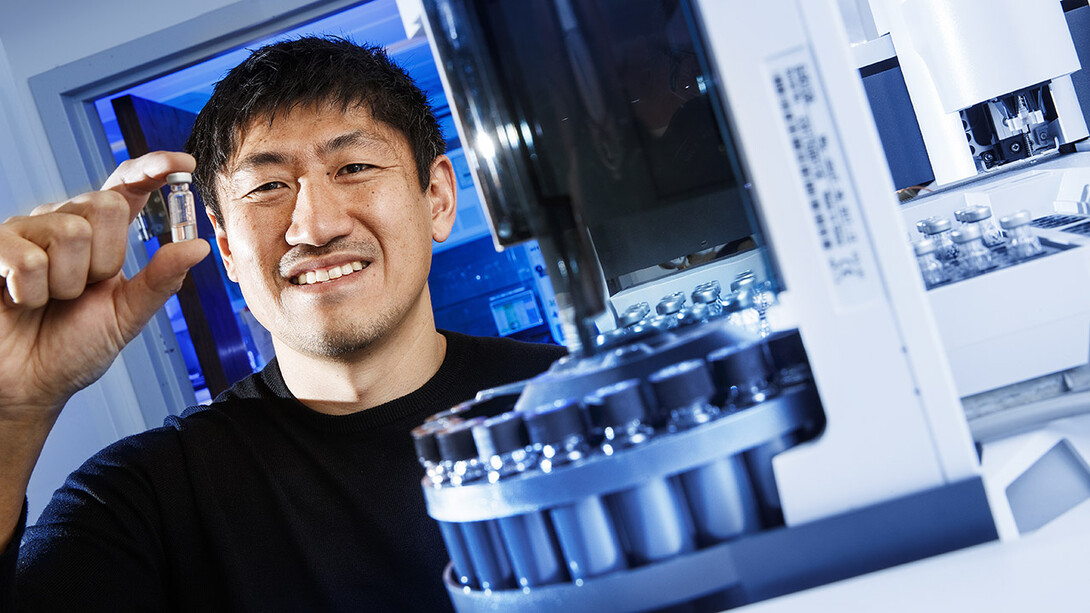

Missteps in metabolism, the process that converts food into energy, is implicated in hundreds of human disorders — not to mention the unwelcome middle-aged spread. Yet much about this complex, essential function remains unknown. Nebraska biochemist Toshihiro Obata is investigating a key component of metabolic regulation that will improve scientific understanding of metabolism and the many ways it can go awry.

Obata, assistant professor of biochemistry, earned a five-year, nearly $750,000 Faculty Early Career Development Program award from the National Science Foundation to continue his research.

“Metabolism is very closely related to the performance of organisms,” Obata said. “What we know about regulating metabolism is very little. Maybe our research can elucidate a new regulatory step where the interactions of proteins play an important role.”

Although metabolism is most commonly maligned for its role in body fat, the biochemical process provides the fuel that allows organisms to breathe, digest food, grow and repair cells, build vital compounds and eliminate wastes, among many other functions. Metabolism is organized into a series of chemical reactions, or pathways, coordinated by a vast network of enzymes that respond to changes in the cell’s environment, maintaining stability.

Many of these enzymes are organized into multi-enzyme complexes, structurally distinct collections of enzymes working together to speed up or slow down steps in the pathway. The role of some of these complexes has been studied in test tubes. Obata’s research will help settle debate about what is actually happening in living cells.

He and his team are investigating multi-enzyme complexes in yeast responsible for the Krebs, or TCA, cycle involved in cellular respiration. The researchers will manipulate enzymic interactions within multi-enzyme complexes to study the effects on metabolic activity. Similarly, the team is studying how changes in metabolic activity affect the complexes’ structures and interactions.

Obata’s research may help uncover genetic mutations that lead to metabolic disorders related to enzyme complex formation. The dysfunction or absence of key enzymes disrupts pathways, resulting in myriad known genetic disorders, such as the metabolic disorder phenylketonuria, or PKU, and Tay-Sachs disease, responsible for destroying nerve cells. Malnutrition and some diseases, such as diabetes and hypothyroidism, also interfere with metabolism.

Because metabolism and multi-enzyme complexes are involved in so many vital functions in nearly all living organisms, better understanding metabolic regulation will have other, wide-ranging benefits. In plants, for example, scientists may be able to improve crop development, resilience and yield. Metabolic pathways are also involved in creating compounds used in medicine, food additives and cosmetics. Obata’s research may lead to new or improved methods of synthesizing useful compounds.

Obata will use the award to educate students and the public about the role enzymes play in regulating metabolism. He’s developing hands-on activities in which participants create paper models then role-play as individual enzymes, working together to accomplish a metabolic function. Undergraduate students have given trial runs positive reviews, Obata said.

The prestigious NSF grant, known as a CAREER award, supports pre-tenure faculty who exemplify the role of teacher-scholars through outstanding research, excellent education and the integration of education and research.