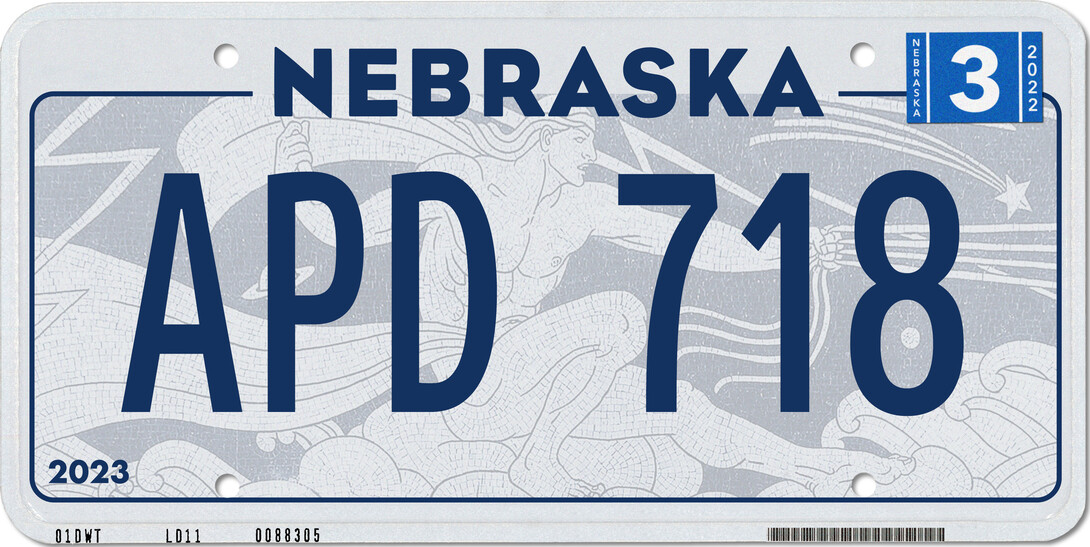

As the new Nebraska vehicle license plate was unveiled May 31, citizens were reminded of the grandeur in their state capitol building.

For nearly 100 years, Nebraskans have been well-acquainted with the remarkable artwork from floor to ceiling in the building, but lesser known is the University of Nebraska connection.

The license plate now features the “Genius of Creative Energy” mosaic, the first floor mural that visitors see on the floor of the Great Hall when entering from the vestibule. The Great Hall boasts murals throughout, representing the “Life of Man.”

The floor murals were created by artist Hildreth Meiere of New York. She was commissioned for the floors and some ceiling artwork by capitol architect Bertram Grosvenor Goodhue, but worked closely with thematic consultant Hartley Burr Alexander, an anthropologist and professor of philosophy at the University of Nebraska. Alexander was asked to join the effort in 1922, when construction began. Through his consulting work on the project, Alexander helped develop the Nebraska State Capitol’s inscriptions as well as the themes of the external and internal artwork.

Following Goodhue’s death in 1924, Alexander wanted to preserve their architectural and artistic vision for the rest of the project and wrote the thematic program, “Nebraska State Capitol: Synopsis of Decorations and Inscriptions,” in 1926.

For the floors in the Rotunda, Alexander and Meiere relied on the expertise of Erwin H. Barbour, a paleontologist and director of the University of Nebraska State Museum. Barbour was well-regarded as a scientist and served as the museum director from 1891-1941, but he also had artistic talents.

Barbour leaned heavily on his artistic side in the 1920s, as he worked on the design and construction of what would become Morrill Hall, which opened in 1927. Also in 1927, Barbour was tasked with providing detailed sketches of the prehistoric life on the prairie — life he’d studied as fossils. Barbour created dozens of delicate images on tissue paper for Meiere, who incorporated the creatures into the guilloches, or bands, encircling the five main medallion murals in the Rotunda.

For decades, Barbour’s drawings were lost to time, until some were found in 1982 and donated to the Capitol Archives.

Viewing the tissue paper sketches inspired Robert Diffendal, emeritus professor in the School of Natural Resources, to write both a children’s coloring and activity book and a guide book explaining the Rotunda fossil murals. The books, launched in 2015, have been archived through the University Libraries’ Digital Commons, where they can be downloaded for free.

“These images captivate thousands of visitors each year,” Diffendal said in 2015. “I’ve heard parents, tour leaders and teachers struggle to describe what they’re looking at when they’re looking at the mosaics. I wanted to put something together to give them a fighting chance at telling kids what these mosaics are depicting.”