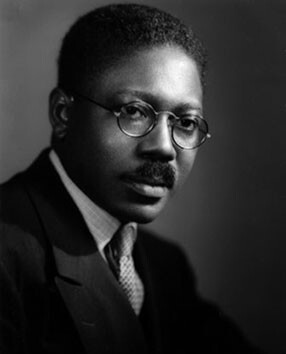

Four prints by Aaron Douglas, the first African American to earn a fine arts degree from the University of Nebraska and leader of the Harlem Renaissance, are on display at Sheldon Museum of Art.

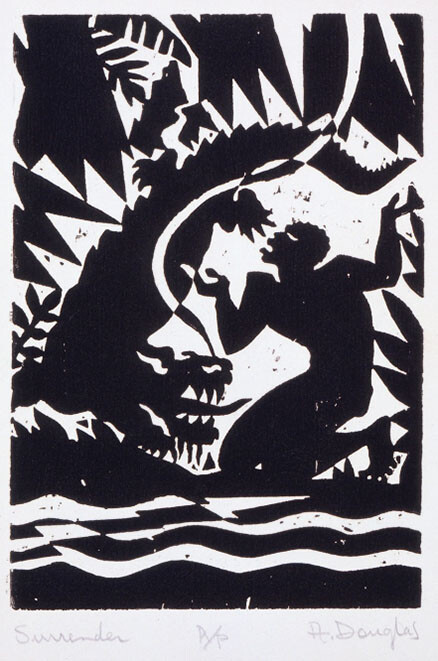

The woodblock prints, part of Sheldon’s “Re-Seeing the Permanent Collection” exhibition, were commissioned by Theatre Arts Monthly for Eugene O’Neill’s drama “Emperor Jones.” The play, which helped launch the career of actor, singer and civil rights activist Paul Robeson, tells the tale of Brutus Jones, an African American man and former Pullman porter who is jailed for killing another black man in a dice game, escapes to a small Caribbean island and sets himself up as emperor. The production has been credited as the first Broadway show with a racially integrated cast.

The prints, titled “Surrender,” “Flight,” “Bravado” and “Defiance,” display a hard-edged style and geometric art deco-inspired form typical of Douglas’ printed work from the time.

>> For a list of diversity events on campus, including Black History Month activities, click here.

Douglas, born in Kansas, received a Bachelor of Fine Arts from the University of Nebraska in 1922. While on campus, Douglas was an active member of the Art Club (see photo below) and Kappa Alpha Psi, a professional African American business fraternity.

He taught for one year at Lincoln High School in Kansas City, Missouri, before moving to New York City with dreams of setting out for Paris, France. Friends and acquaintances urged Douglas to remain in Harlem, dedicate himself to his art and assist with the growing intellectual and cultural movement of black America.

Douglas was soon recruited to create woodcuts for “The New Negro,” which was edited by Alain Locke and became the seminal publication of the Harlem Renaissance. The collection of essays, poetry and fiction helped outline the goals of black artists, including a belief shared by Douglas and Locke that a new artistic philosophy could redefine black culture in the United States and show that blacks could contribute positively to the United States.

In his art, Douglas developed themes relevant to blacks in America, often incorporating African imagery. His “primitive” style came to represent the Harlem Renaissance — a cultural, social and artistic movement that took place in Harlem between the end of World War I and the middle of the 1930s. Douglas’ work has led to him being called “the father of black American art.”

By 1936, Douglas had become a leading figure in the African American art community. His oil painting “Window Cleaning” was displayed in a March 1936 art exhibition at the University of Nebraska’s Morrill Hall. The Nebraska Art Association purchased the painting for $100 and it is now a part of Sheldon Museum of Art’s permanent collection.

Douglas left Harlem in 1937 to found the art department at Fisk University in Nashville, Tennessee. He taught at the university until retiring in 1966.

For more information on Douglas’ life, click here.

“Re-Seeing the Permanent Collection” also includes Lorna Simpson’s “Backdrops circa 1940s,” a diptych that features a cropped photo of Lena Horne with a star background and a full-view of an unidentified black woman posed with a moon and stars.

Simpson is an African-American photographer and multimedia artist from Brooklyn, New York. Her work rose to prominence in the 1980s and she is one of the leading artists of her generation. Sheldon will explore Simpson’s work in a “Look! at Lunchtime” presentation, 12:15 to 12:30 p.m., Feb. 16 in the gallery and live on Facebook. The presentation, which is free and open to the public, will be led by Abby Groth, assistant curator of public programs.

For more information on Douglas’ artworks in Sheldon’s permanent collection, including “Window Cleaning,” click here.

“Re-Seeing the Permanent Collection” will be on display in the museum through July 30.