The movement of water across the globe causes small fluctuations in the planet’s gravity field. One wouldn’t notice the difference by clocking the speed of falling apples, but a set of NASA satellites was tasked with detecting these seemingly imperceptible gravitational changes from space, starting in 2002. What NASA’s Gravity Recovery and Climate Experiment (GRACE) satellites recorded helped tell the story of water movement above and below the Earth’s surface.

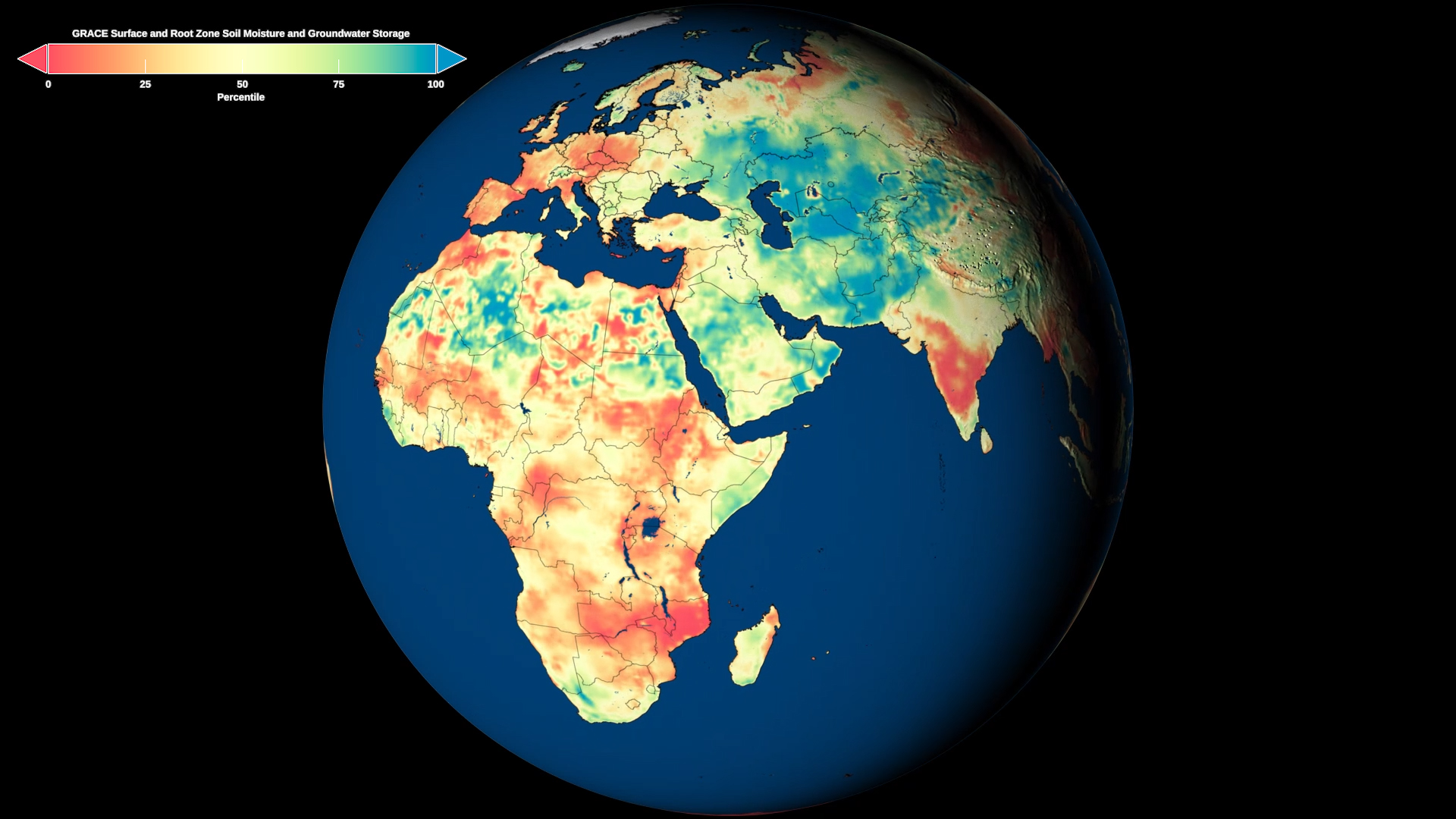

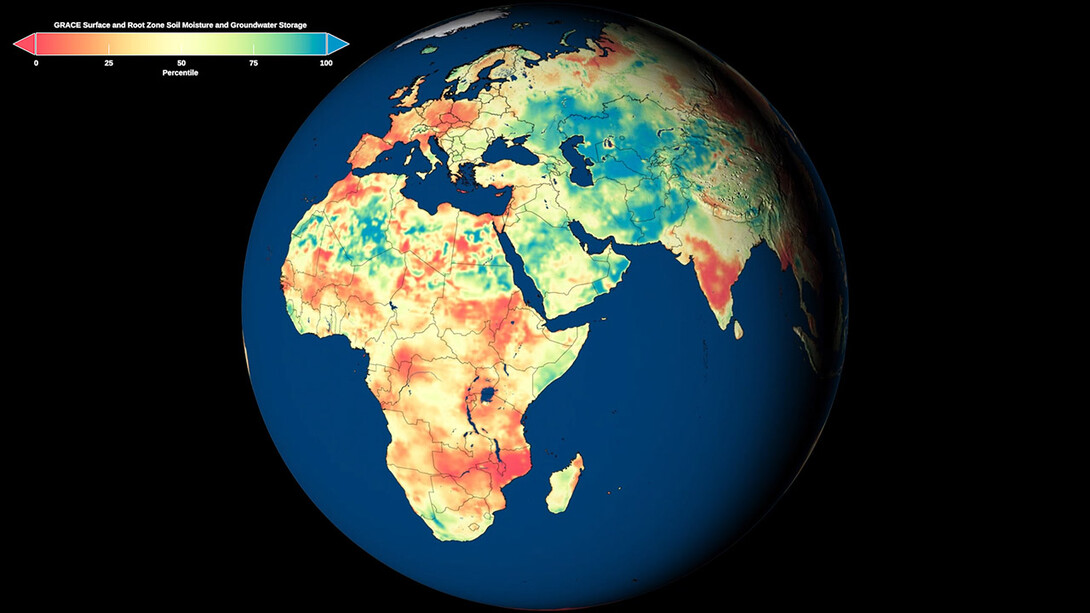

Now, thanks to help from two centers in the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s School of Natural Resources, information from the GRACE satellites’ upgraded replacements is being used to produce and share first-of-their-kind maps of topsoil, root zone soil and groundwater moisture around the world, as well as 30-, 60- and 90-day forecasts of wet and dry conditions across the continental United States.

Brian Wardlow, director of the university’s Center for Advanced Land Management Information Technologies (CALMIT), said that the snapshots of conditions in deep aquifers that the GRACE satellites provided have no remote-sensing equivalent.

“This is the culmination of almost a decade-long partnership with NASA scientists to develop remote-sensing-based monitoring tools and now forecasts for both the national and global drought-monitoring community,” Wardlow said.

With the GRACE-FO (Follow-On) satellites, the information about dry or wet conditions at the three depth levels that was only available for the Lower 48 states is now available to the world. Providing that information to drought monitors has been a key goal since the Nebraska centers began collaborating on GRACE projects with NASA.

“The idea of getting improved information on soil moisture conditions has always been a critical area of need (for drought monitoring),” said Wardlow, the principle investigator on the projects. “That’s always been one of the holy grails of remote sensing or drought monitoring. That’s always been a key information gap. What makes this more unique is it’s the only remote-sensing drought indicator approach that also assesses groundwater. This is really a first of its kind.”

Now, the maps could inform drought-monitoring operations globally, said hydrologist and project lead Matt Rodell of NASA’s Goddard Space Flight Center in Greenbelt, Maryland.

“The global products are important because there are so few drought-monitoring products out there,” Rodell said. “Droughts are well-known when they happen in places with a populated area. They’re usually well-documented. But then there are other droughts that happen, and no one really takes notice. So it’s interesting also to have a product like this where you can say, ‘Wow, it’s really dry there, and no one’s reporting it.’”

Many developing countries do not have much or any groundwater- or soil moisture-monitoring infrastructure. Providing a resource that experts in those countries can factor into their drought-monitoring efforts can help build resiliency worldwide, Wardlow said.

“Drought is really a key area moving forward with a lot of the projections of climate and climate change,” Wardlow said. “The emphasis is on getting more relevant, more accurate and more timely drought information, whether it be soil moisture, crop health, groundwater, streamflow — GRACE is central to this. These types of tools are absolutely critical to helping us address and offset some of the impacts anticipated, whether it be from population growth, climate change or just increased water consumption in general.”

Maps are hosted online on the National Drought Mitigation Center website, and the remote-sensing tools for operational drought monitoring that utilize NASA technology were developed in collaboration with CALMIT. NASA’s GRACE-FO satellites began orbiting Earth after NASA decommissioned the GRACE satellites in 2017.

The GRACE satellites provided information about soil moisture and groundwater levels across the Lower 48 states. Authors of the U.S. Drought Monitor have used it for years to create the weekly map that depicts the most current conditions of drought in the country and informs federal financial-aid decisions due to drought losses.

Agricultural producers have long monitored soil moisture and groundwater levels for the sake of their crops’ health. Surface and root zone soil moisture levels are telltale signs of plant health, and farmers in areas with groundwater may use it more for irrigation when conditions are dry. While there are groundwater monitoring stations across the country that U.S. Drought Monitor authors can consult, satellite observations have told a more detailed and efficient story of soil moisture and groundwater, said Brian Fuchs, National Drought Mitigation Center climatologist and U.S. Drought Monitor author.

“GRACE was one of the first satellite platforms that was looking at soil moisture and groundwater moisture itself,” Fuchs said. “There really wasn’t anything out there doing that at the time. We had a lot of different soil moisture models, and we had groundwater data that was piecemeal. Each state was putting their own information out, and you would have to bounce to many different states if you wanted to get a regional picture of groundwater. From the Drought Monitor side, having that in our back pocket to start looking at another input, another piece of data that really wasn’t out there at the time and was needed, was pretty important.”

Along with providing global outlooks, the GRACE-FO data is informing a set of forecasts that project dry and wet conditions 30, 60 and 90 days out for the continental United States. The GRACE-FO data provides the baseline information, which is combined with a weather model that provides rainfall information.

“It is going to (help) a broad scope of people,” Fuchs said. “You’re going to see anyone from individual producers from the ag sector using it, as well as water supply managers, policymakers and different decision-makers at different levels of government who would have the opportunity to look at that. Even the folks at the Climate Prediction Center who do the long lead outlooks and the long-range forecasting — they could incorporate some of this data into their products.”

To produce the information that fuels these new products, the GRACE-FO satellites orbit in tandem about 137 miles apart. The raw data sent to Earth is a collection of measurements showing how far apart they are as they circle the globe. In areas with slightly stronger gravity, the lead satellite is initially pulled ever so slightly away from its trailer. Then the trailing satellite returns closer to its twin as it passes over the gravity anomaly. Microwave signals sent between the satellites measure the imperceptible distance differences that take place, and tell the story of how mass — most often water — is moving across the planet.