Welcome to Pocket Science: a glimpse at recent research from Husker scientists and engineers. For those who want to quickly learn the “What,” “So what” and “Now what” of Husker research.

What?

By living inside single-cell paramecia, some green algae shield themselves from the chloroviruses that can infect them. But in 2016, Nebraska researchers reported that tiny crustaceans sometimes consume and partly digest paramecia before excreting them into the water, exposing the otherwise-safe green algae to infection.

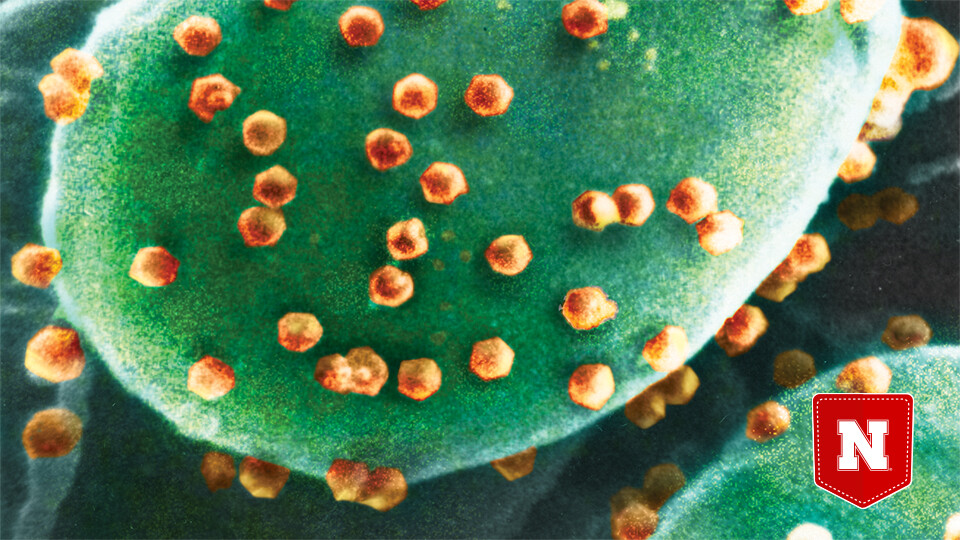

Hundreds of chlorovirus particles can attach themselves to the outer surface of a paramecium, gaining near-instant access to any exposed algae. But given that viruses are generally considered inanimate — encountering infection opportunities only through random collisions — the chlorovirus numbers seem higher than expected by chance.

So what?

Recent experiments from the Nebraska team suggest that chloroviruses may actively attract paramecia, possibly via chemical-based signaling.

When presented with multiple paths, paramecia were up to five times more likely to migrate toward larger vs. smaller concentrations of chlorovirus particles. The paramecia also showed an affinity for chlorovirus-infected algae cells over uninfected cells.

Though the team has yet to identify a specific method of attraction, the experiments represent unprecedented evidence that viruses can exercise at least some control over their relatively distant surroundings.

Now what?

Follow-up studies should investigate the specific nature of any attraction and whether other viruses exhibit similar influence, the team said.