Custer State Park in western South Dakota is one of Thomas Gannon’s favorite places to go birding.

But as someone who grew up a half-Lakota boy in that region, the name of the park is a reminder of some of the painful history of the Great Plains.

“I drive into the park and it’s named after an Indian killer,” Gannon said.

He also enjoys birding trips to Indian Cave State Park, Wagon Train State Recreation Area, and Stagecoach Lake, each of which has a name steeped in the same legacy.

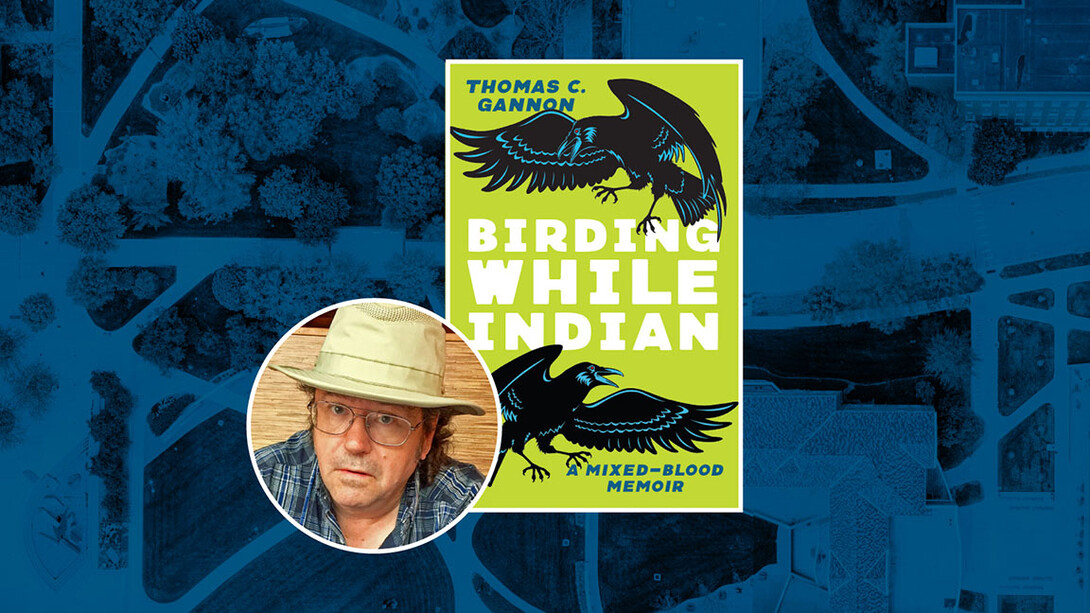

Gannon, associate professor of English and ethnic studies at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, released “Birding While Indian: A Mixed-Blood Memoir” in June. In the book, he delves into that history, birding and his own life and family.

He started birding while he was elementary school in Rapid City, South Dakota.

“I’d climb a chain link fence, cross the interstate, and there I was,” Gannon said. “The third or fourth time there, this great-horned owl flew over my head, just totally silent, and I thought, ‘This is wonderful, this is great.’ I didn’t realize at the time but unconsciously, I was escaping the whole family situation, the racial politics of western South Dakota.”

In fact, the book originated as Gannon was writing about his experience at what is now called Red Cloud Indian School on the Pine Ridge Indian Reservation. Around the time he started at the school, he saw his first common goldeneye.

“I thought, I’ll wrap that goldeneye experience around the narrative of the boarding school and flash back and forth between the two,” Gannon said. “So that gave me the idea of writing a whole book based upon specific bird sightings.”

Gannon opens up about other difficult aspects of his life and childhood, including encountering racism and abuse. A chapter about the long-tailed duck, which used to be called the oldsquaw, recounts some memories Gannon has of his mother.

“Not only did Mom’s co-workers call her a squaw and she’d come home crying from work until the day she retired, but I remember before my dad left when I was just a little kid, he’d call her that, too, as he was beating her down the stairs,” Gannon said.

He also shares stories about his grandmother, his great uncle and other family. Writing the book helped him recognize how important it was to him to tell his mother’s story, too.

“It wasn’t until the end of the book that I realized that I was actually writing this for her, giving her a voice,” Gannon said.

The book also overlaps with Gannon’s academic life. His previous book, “Skylark Meets Meadowlark,” was a close examination of British romantic and Native poets and their depictions of birds. Through this research, he noticed some common threads.

“Natives have always been conflated with the wild, non-human animals,” he said. “Part of it is actual cultural reality for specific tribes, but above all, Western colonizers looked at wild Indians and wild birds and other animals as pretty much synonymous.”

Gannon said this viewpoint, along with a general disconnect from nature, resulted in similar fates for bird species that have gone extinct and tribes that were relocated or wiped out.

“My claim in my theoretical research is that such extirpation was performed for the same reason,” he said. “A fear of the wild, a need to control the wild, contain the wild, get rid of the wild.”

The book includes poems and history alongside anecdotes about birding and Gannon’s life and family. The structure also happens to be in keeping with the “mixed-blood” subtitle. Gannon said the writers he teaches in class, like N. Scott Momaday and Leslie Marmon Silko, influenced his own writing, including when it comes to genre.

“Almost all the famous Indian writers are mixed blood and much of their writing itself is mixed genre,” he said.

Even though the book is framed within personal birding experiences, incorporating the history of the locations became inescapable, like in a chapter about the canyon wren, where he reflected on the the namesake of Custer State Park, General George Armstrong Custer, and what that history means to Native Americans in South Dakota. Gannon wants students to realize that this legacy didn’t end generations ago and the ripples still affect people now.

“Indians are still around, and the ideology of the 19th Century Indians Wars, Manifest Destiny and Western Colonialism are still alive and well today,” Gannon said. “Also, I’d let them realize how cool birds are.”