At least since the Neolithic Revolution, alteration of the environment has been a centerpiece of human activity.

As people built farms, cities and ever-more-complex civilizations, they drained swamps, felled forests, plowed prairies, dug canals, excavated mines and changed their surroundings in myriad ways in a quest for health, comfort, security, prosperity and prestige.

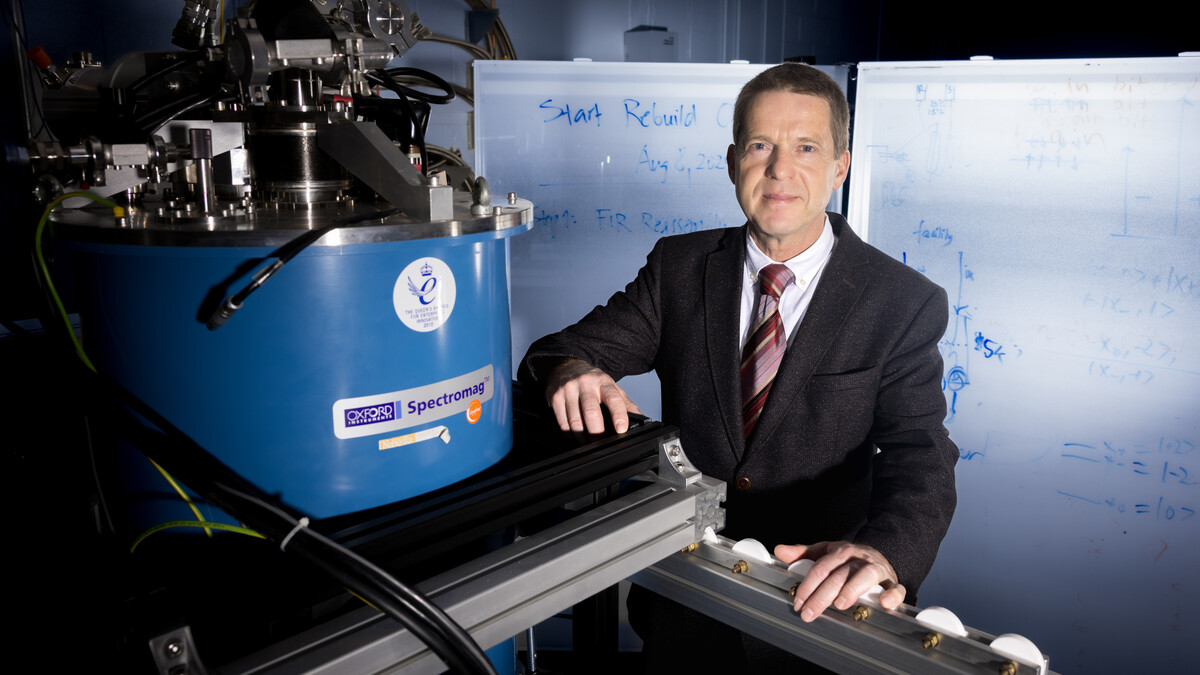

It’s a topic that fascinates University of Nebraska-Lincoln historian James Garza, whose recent research has become increasingly focused on environmental history.

After a decade of study, including a year living in Mexico City, annual trips to the national archives there and a research trip to London, Garza is reaching the finishing stages of a book about how the Mexican government under President Porfirio Diaz, partnered with a major British engineering firm to build a 30-mile drainage canal outside Mexico City at the end of the 19th century.

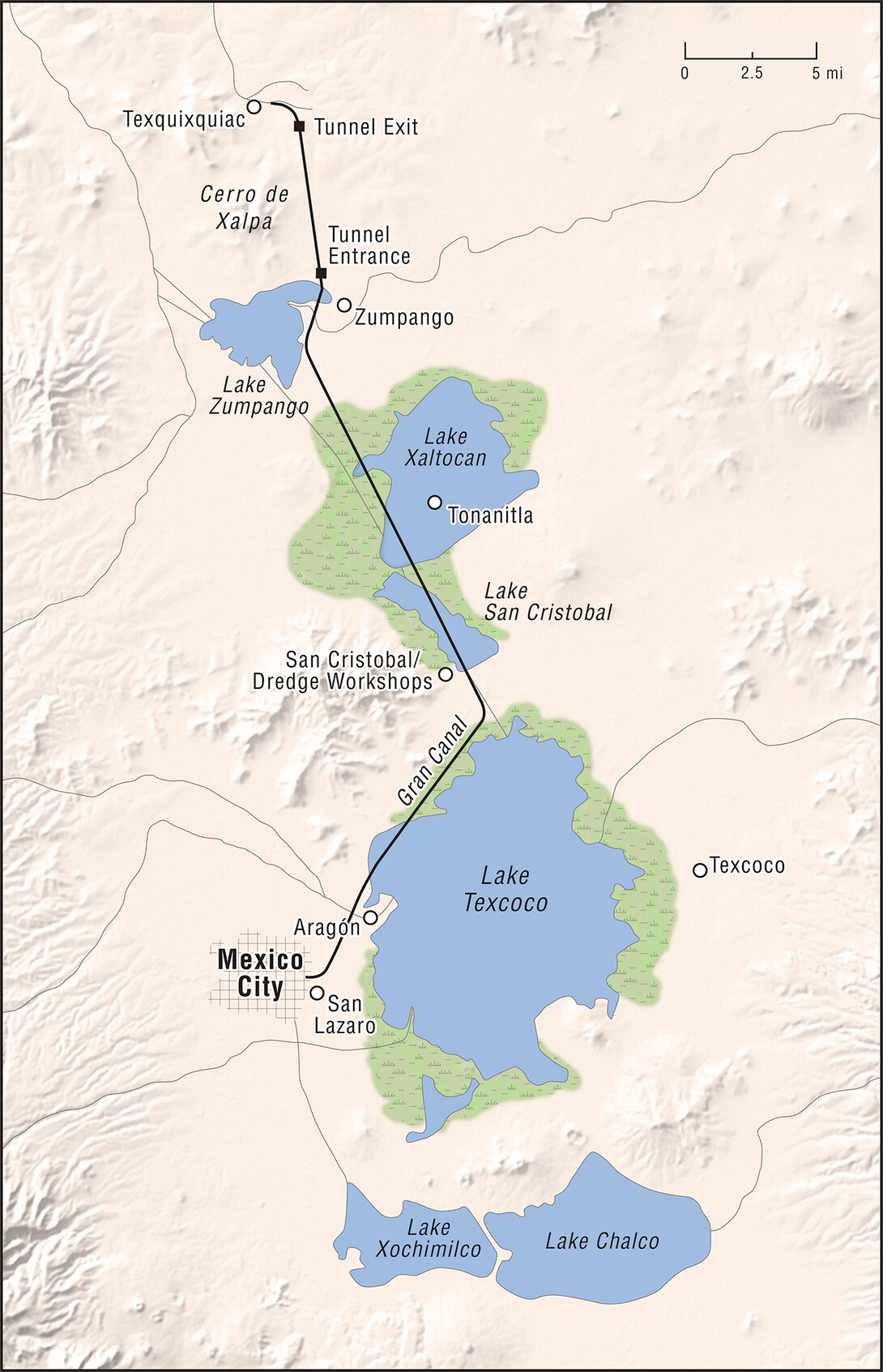

The Gran Canal del Desagüe was an engineering triumph that provided flood control, improved sanitation and propelled Mexico City to become one of the world’s largest and most beautiful metropolitan areas.

Gran Canal del Desagüe

But Garza, an associate professor of history and ethnic studies, observes that progress came at a cost that the planners and builders may have failed to recognize. Most of the marshy lakes that once bordered Mexico City were destroyed, along with them the birds, fish, plants and insects that provided an economic and cultural foundation for the indigenous people whose lives and livelihoods centered around the lakes.

“I’m trying to capture this episode in the transformation of the world from the way it was at the dawn of the 20th century,” Garza said in a recent interview. “At the end of the 19th century and at the early 20th century, there still were glimpses of a way of life that had existed for centuries. The lakes were a source of life for the rural people, a source of food and building materials, hunting and fishing. All of that is gone now, that way of life.”

As yet untitled, Garza’s book is under contract with the University of Nebraska Press and he expects it will be published in 2026. Additionally, his studies of the Gran Canal and its impact on the ancient lakes of the Valley of Mexico are spinning off into a related topic: the international feather trade that sprang up during the 19th century.

During the Gilded Age, it became popular, particularly among the wealthy, to wear hats adorned with the feathers of exotic birds, including herons, egrets, birds of paradise and even flamingoes.

“One of the things that happened in Mexico City, is that migratory birds that wintered there, including Sandhills cranes, were hunted nearly to extinction for their feathers,” Garza said. “The feathers were worth their weight in gold. These birds represented wealth and beauty — beauty for commercial gain. In Mexico City, they would hunt them by the tens of thousands.”

Garza gave a well-received science slam presentation on his feather research during Nebraska Research Days in November 2024. He is eager to write a follow-up book that will tell the complete story of the feather trade, including its impact on bird species and the indigenous people who hunted the birds.

Garza said he has been fascinated with environmental and social history since he was growing up along the U.S.-Mexico border in Laredo, Texas.

“I was interested in the geology and the Rio Grande and how everyday life was affected by the temperature and the weather and the land there,” he said.

Garza has incorporated his research into his classes throughout two decades on UNL's faculty. In his Latin American and Mexican history courses, for example, he talks about the Mexicans who resisted the Gran Canal as a way to keep the human narrative at the core of his lessons. A popular freshman-level class, "The History of Modern Crime," takes a case-by-case approach to modern criminality, where he links crimes that occurred in the 19th and 20th centuries to the development of capitalism and state power.

There’s no good or evil in this story — it’s a historical process. Communities are resilient and they change. This is what happened in the past, this is what we did in the past and now we have different goals into the future.

Garza's love for Mexico City inspired his return to environmental history topic. He finds it a magnificent place to be, full of culture and history. Yet it has a history of floods and earthquakes, while climate change is making it more vulnerable to catastrophic water shortages.

The city sits in the Valley of Mexico, a high-altitude basin surrounded by mountains. Garza said its location in essentially a stone bowl contributes to drainage and water supply issues that date back to the Aztecs before the 15th century.

“The Aztecs were the original engineers,” he said.

The Aztec capital, Tenochtitlan, was established on an island crisscrossed by canals. The Spanish built their colonial capital atop the Aztec city, remnants of which still surface during construction projects. By 1900, the lakes had subsided into six shallow bodies, with Lake Texcoco the biggest – and most polluted by the city’s sewage.

"Then the lakes slowly died out because of development and population growth," Garza said. "Mexico City just grew and grew. The lakebeds were just too valuable. Lake Texcoco was turned into subdivisions and a park. A new airport was built on a lakebed in the northern suburbs -- and wooly mammoth bones were found during excavation."

The only natural lake remaining today is Lake Xochimilco, basically a lagoon and wetland where tourists go for boat rides. Most of Lake Texcoco, which once measured more than 2,000 square miles, has been paved over by the city.

“The Spanish and post-independence governments always saw the water as an obstacle,” Garza said. “They wanted to transform into a modern city and the water was an obstacle. But for the indigenous communities there, the lakes were part of their way of life.”

Spurred by serious flooding in the mid-16th and early 17th centuries, as well as the lakes’ increasingly fetid water polluted by the city’s waste, the Spanish government developed flood control and drainage projects but lacked the technology to successfully complete ambitious plans that called for river diversion and the construction of canals and tunnels. It wasn’t until the late 19th century that the government under Porfirio Diaz was able to assemble both the financial resources and engineering expertise, with Mexican engineers partnering with a British firm, S. Pearson and Son, to use five massive steam-powered dredges to excavate the channel. The canal was officially inaugurated by Diaz on March 17, 1900.

Garza said his research offers lessons about resiliency and environmental impact for Nebraskans as well as people in Mexico and around the world.

“I don’t think it was a mistake to build the canal,” he said. “It introduced railroads, better roads, community improvements. But they did end up giving up a way of life.”

“The rich ecology of the Valley of Mexico is completely gone, for reasons that may have not been apparent to people as they developed it,” he said. “There’s no good or evil in this story — it’s a historical process. Communities are resilient and they change. This is what happened in the past, this is what we did in the past and now we have different goals into the future.”