Richard Graham knows a thing or two about comic books and cartoons, so he was surprised to learn only recently of prolific Nebraska editorial cartoonist Oz Black.

Graham is an associate professor in University Libraries and scholar of the history and use of comic books and graphic novels in both government propaganda and popular culture — but he hadn’t heard of Black until he began research into local and regional comics and cartoon history. The name came into focus while Graham was working with Lincoln cartoon artist Paul Fell.

“Paul is the head of the National Cartoonist Society, Midwest chapter, and in my conversations with him, he let me know about this popular, wildly prolific editorial cartoonist, Oz Black, who worked in Nebraska for a long time,” Graham said.

Oswald Ragan “Oz” Black studied art at the University of Nebraska from 1918 to 1923. He went on to document local news 365 days a year for nearly four decades, first at the Lincoln Star from 1921 to 1927, and then for the Nebraska State Journal from 1930 to 1940. Following his work in Nebraska, Black went to the Minneapolis Tribune, before moving to Denver, where he worked in public relations and as an instructor in cartooning and caricature at the University of Colorado Institute of Adult Learning.

“Pretty soon after that conversation, I was on eBay and purchased an original Oz Black piece,” Graham said.

The purchase spawned an idea. Were there more of these original pieces out there? Yes, and now Graham is preserving original Oz Black cartoons in an online archive, hosted by the Libraries’ Image and Multimedia Collections.

Graham located two large collections in Lincoln, one at Lincoln Public Libraries and one at History Nebraska. Graham and project partner John Wiese, visual resources specialist in the University Libraries, are currently scanning and uploading the known collections, which number about 570 pieces. More than 100 cartoons are already online.

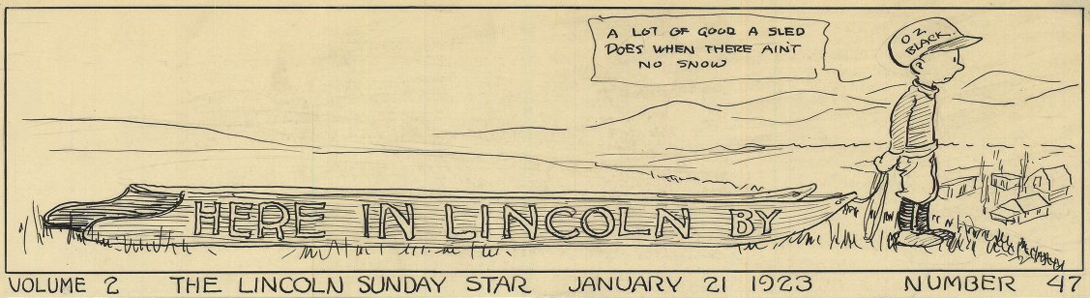

Black used thick cardstock, usually 11-by-16 inches or bigger, to draw the cartoons before they were published on the editorial page of the daily paper. They include boxes, unrelated and unordered, with more than one event or story featured. Titled “Here in Lincoln,” Graham noted that even the header changed each day, depending on what Black wanted to depict.

“Looking at all of these, you can imagine Oz Black sitting down with his coffee, maybe working on an advertisement or illustration, and the news starts filtering in, and as he’s hearing it, he’s drawing his interpretations of those events into these non-paneled comics, so that wherever your eye gazes, you’re getting a snippet of what’s going on, learning new facts, and they were always eye-catching.”

The cartoons are snapshots of Lincoln’s history. Some characters and events are obscure, but there are also references that will be recognizable even now to Nebraskans.

“It’s really fascinating when you look at these as a gestalt and see prominent issues like housing, and even things like Oklahoma football in those days, already in the 1920s, or William Jennings Bryan running for president — again,” Graham said. “There are things long forgotten, but they were memorable at the time. It’s really a neat snapshot into our town and our region 100 years ago.

“There’s incredible value in these illustrations of regional history and making connections to current history.”

Graham said Black’s pieces also show extraordinary artistry and creativity.

“His style is remarkable,” he said. “When we think of cartoons, they have to tell a complete story in a picture in order to be effective. Oz Black had a really accessible style. He was visually very intense and fun to read.”

Graham hopes that the collection will add to Lincoln historical knowledge, provide new primary resources and be a tool for educators at all levels. He plans to incorporate the collection into a spring 2024 class, “History through Graphic Novels,” that he will co-teach with Patrick Jones, associate professor of history.

“It’s also part of the Libraries’ mission to populate the web with primary sources, to provide credible primary documents online for researchers to use,” Graham said. “And these collections are well used.”