A University of Nebraska-Lincoln chemist will lead a new project that will create a unique system of teaching chemistry at Nebraska’s tribal colleges.

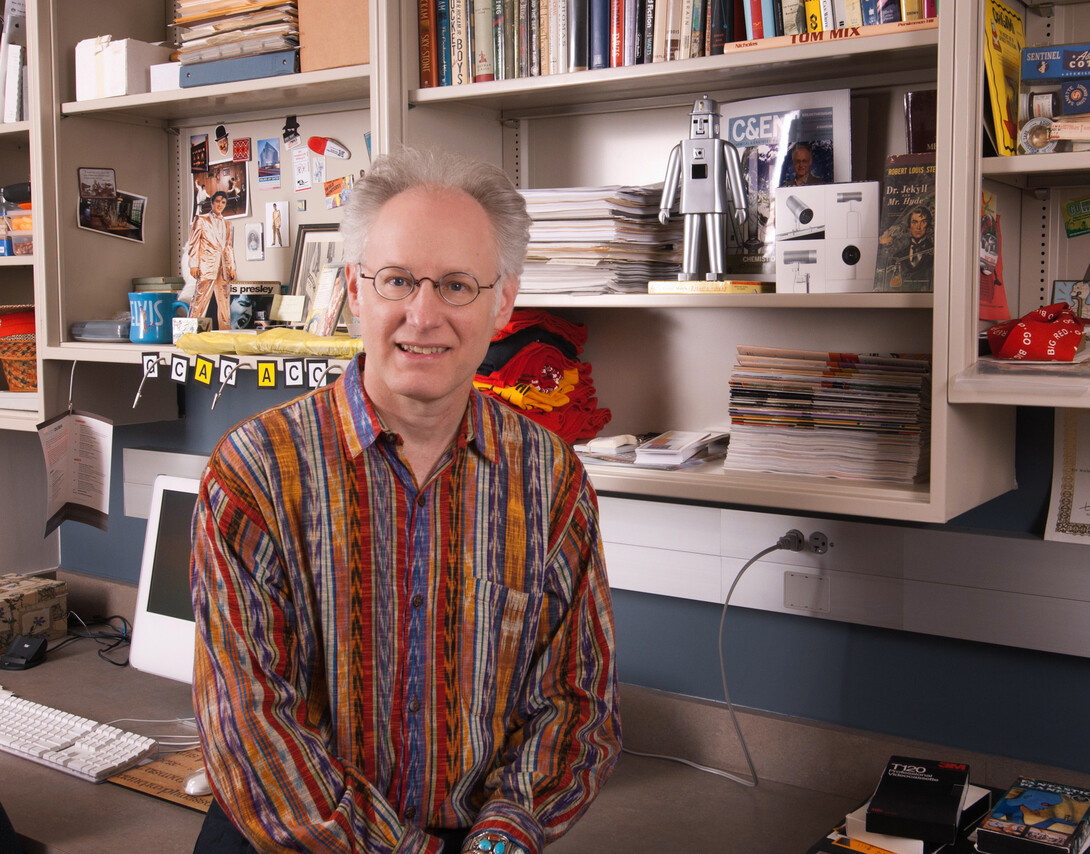

Mark Griep, associate professor of chemistry, will be the principal investigator on the project, made possible through a five-year, $749,000 National Science Foundation grant. The plan involves working with tribal colleges to develop a chemistry curriculum that incorporates real-world topics from the communities the colleges serve.

The grant, a Research Infrastructure Improvement Track 3 award, is part of a pilot program through NSF and EPSCoR – Experimental Program to Stimulate Competitive Research – to target underrepresented populations in science, technology, engineering and mathematics, often referred to as the STEM fields.

Griep applied for the grant upon learning that Nebraska Indian Community College in Macy, Neb., hadn’t offered chemistry courses in six years.

“There is a need,” Griep said. “About two-thirds of their science students are health sciences majors and the rest are environmental sciences majors. So both of them really need chemistry.

“It’s just a matter of getting these courses off the ground and then convincing the students to enroll.”

Griep has proposed calling upon the tribal elders, community leaders, the Nebraska Commission on Indian Affairs and others to create a list of community topics that can be connected to chemistry laboratory experiments to enrich student learning. Possible topics include water and wastewater treatment, Missouri River water quality, organic farming, alternative energy, ethnobotany, honeybee colony collapse disorder and Type 2 diabetes.

Griep researched the literature on indigenous science education and found that providing culturally responsive and reflective materials was recommended. He also learned that other projects that did not involve tribal elders were slower to be accepted by the students.

He said he believes that connecting the courses to the students’ communities will be invaluable. The first year of the grant will be spent identifying these topics and forming coursework around them.

Once the curriculum is established, Griep’s plan is to oversee the instruction through weekly meetings with instructors, whose salaries are funded for four years through the grant. After the first year of classes at Nebraska Indian Community College are complete, the program will expand to Little Priest Tribal College in Winnebago, Neb. Griep said he will work alongside Don Torgerson at Nebraska Indian Community College and Brigid Quinn of Little Priest to develop and launch the programs.

Throughout the five years, Griep plans to disseminate the plan to tribal colleges across the nation, starting with South Dakota. He said community-based curricula such as this could be beneficial to all community colleges as well, since it makes chemistry relevant and accessible.

“I take the approach that there are many interesting things in the world that we can use to show how practical chemistry is,” Griep said. “In the class I teach at UNL, I use as many examples as I can to show my students how much chemistry they’ve actually experienced that is relevant to their lives. My hidden agenda is to get them to think about chemistry even after they finish my class.”

Sarah Zulkoski, outreach coordinator for Nebraska EPSCoR, said placing STEM resources within tribal colleges has been important to EPSCoR’s mission of strengthening science and technology research infrastructure within the state.

“For many years, Nebraska EPSCoR has partnered with the tribal colleges to invest in STEM faculty and needed infrastructure at their campuses, and this EPSCoR Track 3 project will build on our prior investments in ways that are new and culturally relevant,” she said. “We look forward to seeing this project bring about enduring positive impacts in the areas of culturally relevant chemistry education.”