Husker researchers Heather Richards-Rissetto, Richard L. Wood and Christine E. Wittich spent much of June deep underground, up to 30 meters below, taking lidar scans of Temple 16 at Copán, a UNESCO World Heritage site that was once a Mayan metropolis located in western Honduras.

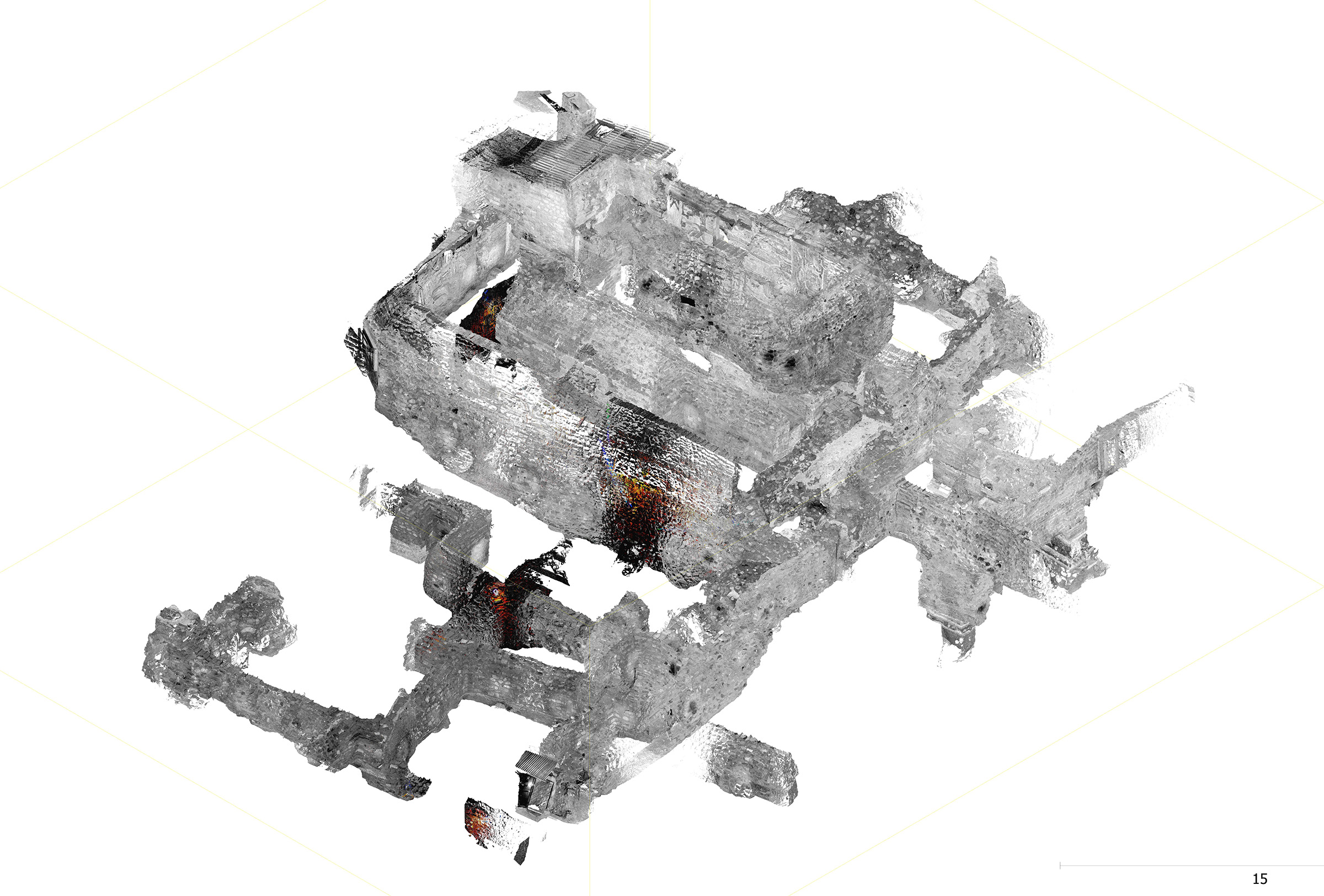

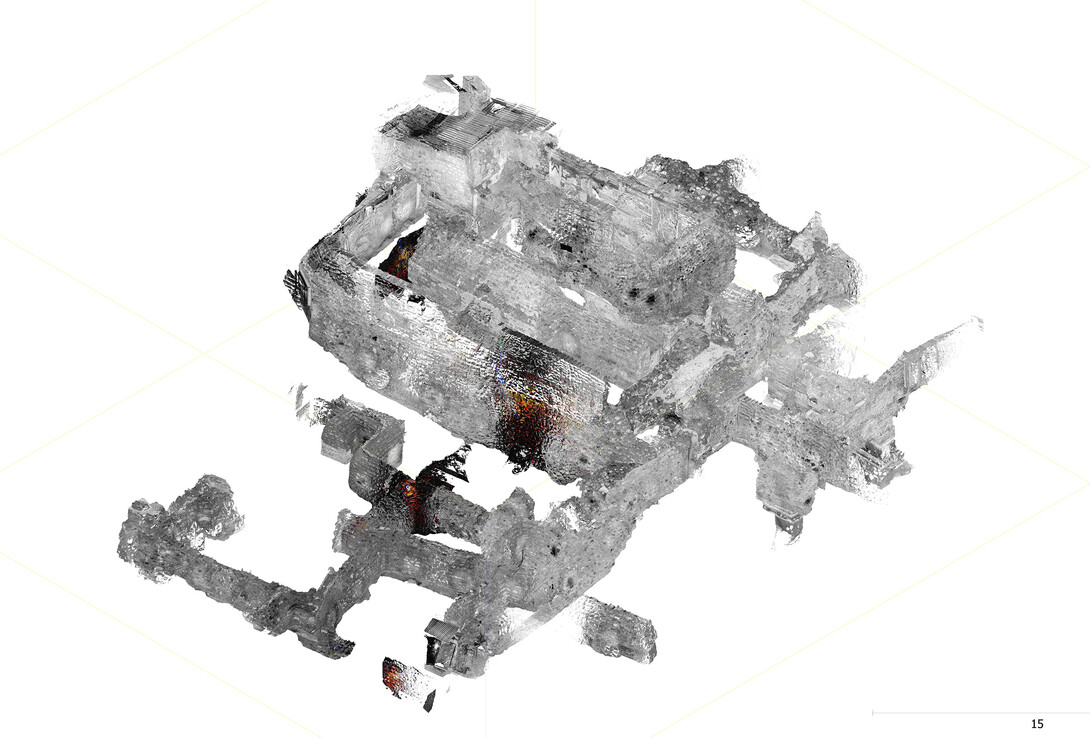

At the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, they have turned the data gathered into 3D geometry of the temple, including its excavation tunnels, the construction that’s taken place over the span of centuries — and the damage.

This novel project’s mission is the continued conservation of Rosalila, a temple that was originally preserved by ancient Mayan, going back to 600 A.D. Now more than 1,400 years old, the three-story, early classic period structure still features its elaborate stucco panels and original paint. It stored numerous artifacts and is engraved inside and out with iconography. This is the first time lidar has been used to scan an underground structure in a tropical climate.

“Rosalila is very unique, because it wasn’t destroyed when another building was built on top of it,” Richards-Rissetto, anthropologist and associate professor in the School of Global Integrative Studies, said. “What the Maya did at Copán was they actually encased it very carefully in stucco to preserve it for the future. We don’t fully understand why this was done, and it’s something very unusual — we don’t typically see that in the Maya region.

“We know it was a sacred place, and that rituals took place there, but we are still trying to understand why this building was preserved.”

Rosalila was discovered by Honduran archaeologist Ricardo Agurcia-Fasquelle through excavation about 30 years ago. Since then, time and the elements of weather and the environment, including hurricane flooding in 2020, have continued to erode and damage the temple.

Courtesy Heather Richards-Risetto scales a ladder to go deeper into Tunnel 16.

Through contacts made during her ongoing research in Copán, Richards-Rissetto was approached to digitally document Rosalila and its home, Temple 16, to find structural damage and help manage it. Richards-Rissetto has used various technologies, including 3D scanning and virtual reality, to digitally preserve and share ancient Maya cities, but this project was a heavier lift. She reached out to Wood, associate professor of civil and environmental engineering, who had experience with lidar and 3D renderings of underground historical sites, most recently Robber’s Cave in Lincoln.

“The key aspect of lidar is the accuracy and location of these tunnels,” Wood said. “With this technology, it enables you to get precise positioning (at the centimeter level), which is a challenge when trying to confirm the tunnels' orientations and locations underneath the temple.

“When you’re in the site, far underground, you can lose your orientation or position, but by looking at it in the digital sense, in 3D, you get that precise positioning and location. This is a key for the advanced modeling and analysis task."

Digitally scanning Temple 16 is the largest project Wood has ever taken on. This project has incorporated more than 1,000 lidar scans, as well as an exterior unmanned aerial system (or drone) survey. The project, as led by Wood, is supported by the Asociación Copán, a nonprofit organization dedicated to the research and conservation of Honduras. The team had to spend hours underground each day to take the scans and dealt with 90-degree heat compounded by 90% humidity in the tunnels, and in some places, low oxygen. Aside from the researchers, the field team included Elisandro Garza, a visiting scholar at Nebraska and current doctoral candidate at the City College of New York, and others who were in charge of running electrical lines down for lighting and to power the scanners.

Wittich, assistant professor of civil and environmental engineering, used her expertise in the tunnels, and now through study of the 3D renderings, to assess and predict structural damage.

“What we’re working on is trying to understand how the structure is currently behaving, how it came to be in its current situation and how it will perform in the future,” Wittich said. “We’re looking at not just the shape and the geometry, but also asking questions about the specific materials, how those materials are distributed and interacting with one another, and what are the primary contributors to current damage.

“From an engineering perspective, we’re harnessing the lidar and materials data to generate computational (finite element) models looking for the primary contributing factors to the structural damage to make recommendations and suggestions, and work with conservationists to preserve this really unique structure.”

One dedicated master's student in civil and environmental engineering, Luis Tuarez, is also working on the project objectives as related to the structural modeling.

Aside from preserving the ancient temple, Richards-Rissetto hopes the project will eventually be a way for all people to digitally connect with Copán and its ancient structures.

“I think one of the next goals is to bring this into virtual reality,” Richards-Rissetto said. “That pipeline is still being developed, but this is a step in that direction.

“This is also providing new avenues for research, which is really exciting. Hopefully, this leads to new insights and new methods for studying ancient architecture revealed through tunneling, not just in the Maya region, but in other areas of the world.”