Editor’s Note — A version of this article by Abby Barmore, at the time a senior sports media and communications major, was originally published by the Nebraska News Service in University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s College of Journalism and Mass Communications on December 30, 2021.

Thirteen-year-old Lindsay Krause stood in awe of thousands of Nebraska fans and the incredible athletes on the court in front of her.

Around her, the sea of red roared to its feet clapping in unison as Nebraska’s band launched into its fight song. The soldout crowd in the Bob Devaney Sports Center encouraged the No. 3 Huskers. They gathered in a timeout, determination sketched on their faces and “Nebraska” scrolled in cursive on their chests. Huskers Head Coach John Cook plotted to stage a comeback against No. 16 Wisconsin in the fourth set.

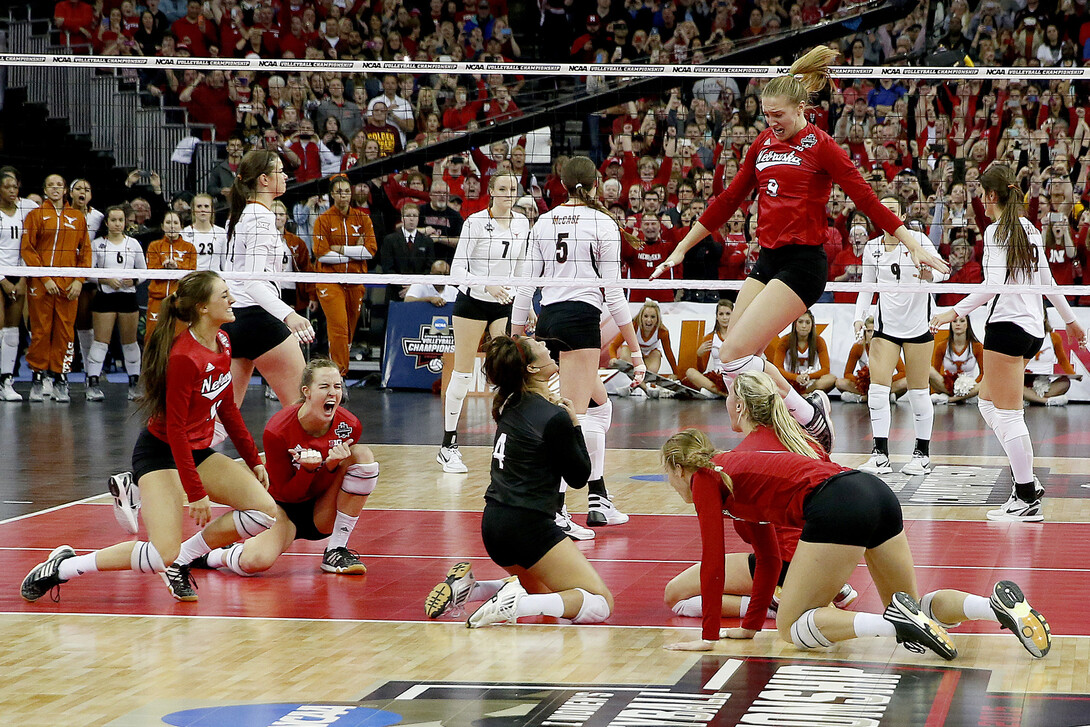

The crowd remained on its feet as the serve flew over the net, dug by libero and future Olympic gold medalist, Justine Wong-Orantes. Krause watched Kelly Hunter set Alicia Ostrander behind her on the right pin. Ostrander crushed the ball with such force it bounced in bounds and launched into the stands.

More than 8,500 fans erupted as two native Nebraskans helped boost the 2015 Huskers to a 22-20 deficit against the Badgers. While the Huskers would go on to lose this set and match, they would eventually fight their way to the 2015 National Championship.

Krause, a Papillion native, always knew Nebraska was good at volleyball but after that moment, she knew she wanted to play volleyball for the Huskers one day.

“It had never really dawned on me how big of a state we were in, how much of a tradition it was at this university,” Krause said.

Nebraska offered Krause a scholarship in the summer before her 2017 freshman season at Omaha Skutt where she would win four consecutive Class B state titles.

Just like Krause, countless young Nebraskan females dream of becoming Husker volleyball players because they see women, just like them, dominating on the court.

“When you see people do it, it seems all the more possible for you to do it,” Krause said. “There’s a lot of things that seem like they’re impossible to do. But as soon as you see other women that are like my age do it, it seems all the more possible.”

Since 1995, when coach Terry Pettit led the Huskers to the program’s first national championship, the sport became a “state treasure,” Cook has said.

Female role models in society

If you can see it, you can be it.

Having someone who looks like you, by gender, by race, ethnicity, sexual orientation or social class can have a “tremendous impact,” Helen A. Moore, professor emerita of sociology, said.

“It’s harder when you can’t see a woman or a woman of the same race or ethnicity or even the same age doing the kinds of work that you think you would like to do, whether it’s on the court, on the field, in an office or working in the athletic industry,” said Moore, who has owned Huskers volleyball season tickets for over 20 years.

Females in Nebraska are exposed to volleyball across the state at their high schools, in their communities and on TV.

“If you’re from a small town in Nebraska, and you see somebody who’s also from a small town in the Midwest, and they’re doing something extraordinary, you might think, ‘Wow, I didn’t know people from my town could do that.’ So, it opens up a possible future self,” Julia McQuillan, professor of sociology, said.

With this exposure comes a higher likelihood that people will have volleyball players as role models. These role models matter, McQuillan said, because if females only see men in leadership positions, their brains might automatically only associate males with leadership.

“One way to change that is to mix up the characteristics of people in those positions,” McQuillan said. “Having what we’d call “counterstereotypical role models” can be really important for changing our default assumptions about who can do what.”

As role models, volleyball players and female athletes can create counterstereotypes by displaying strength, athleticism and other powerful traits that counter the female stereotype of being fragile or weak. These counterstereotypes can be productive, Moore said, if the role models are relatable and viewed as humans — not larger-than-life figures.

“If you make the individual athletes either so far removed from the everyday that nobody can be like that, or you force women athletes to abide by some other sets of stereotypes, it’s very hard for those counterstereotypes to be authentic,” Moore said. “In Nebraska, you’re going to be exposed to certain things. Can Jordan Larson come from Hooper, Nebraska, and be one of the greatest players internationally? Yes. But not every little girl is going to see that the same way.”

What happens when people can’t see similar people doing what they aspire to do? Moore said they tend to become discouraged from their dreams.

“If you can’t see yourself, and if other people can’t see you in that role, you’re much more likely to be discouraged,” Moore said. “We tend to have lowered expectations from people when we don’t see other people like them being successful.”

These lower expectations, Moore said, can come in the form of a teacher not devoting as much time to that student or parents not providing the emotional or financial support necessary to help their child reach their dreams.

“Maybe not every kid would want to be a Huskers volleyball player,” McQuillan said. “But, I think the better message would be, ‘If you really want to go after something, it’s probably going to take work.’”

Title IX opened a door

In 1972, with the passing of Title IX, which prohibits gender discrimination in federally-funded educational institutions, Pettit said everything changed and not just in sports. But sports provided one of the most visible stages. Not only did Krause grow up watching championship volleyball players, but every single person she looked up to was female. Role models like former Huskers outside hitter and Olympic gold medalist Kelsey Robinson; two-time Huskers national champion Mikaela Foecke; and Minnesota’s Hannah and Paige Tapp, who both played on Team USA.

“It’s super important to have women that you can look up to, especially in a skill or maybe a profession that you want to accomplish in your life,” Krause said.

She looked to them because they were “exemplary” players, and they were good people.

“I need to look at these women in powerful positions, doing what they can and they’re rocking the game,” she said. “And Jordan Larson, obviously, but she doesn’t even seem like she needs to be named.”

Larson, a Nebraska player from 2005 to 2008, led the Huskers to its 2006 National Championship, was named the 2008 Big Ten Player of the Year and a two-time First-Team AVCA All-American. Her jersey was retired in 2017, and she was inducted into the Nebraska Athletics Hall of Fame in 2020. As a young girl growing up in Hooper, a town of less than a thousand residents, Larson said Michael Jordan was her role model.

“I think to have female athletes in a place where (young girls) can actually see tangibly is really important,” Larson said. “I think we’re starting to make some headway in that, but I think there’s still a long way to go.”

Getting females to play sports isn’t the only goal, Pettit said.

“You want them to inspire to do whatever they want,” he said. “It isn’t just inspiring them to be volleyball players, you want to inspire them to take risks.”

Literally seeing it

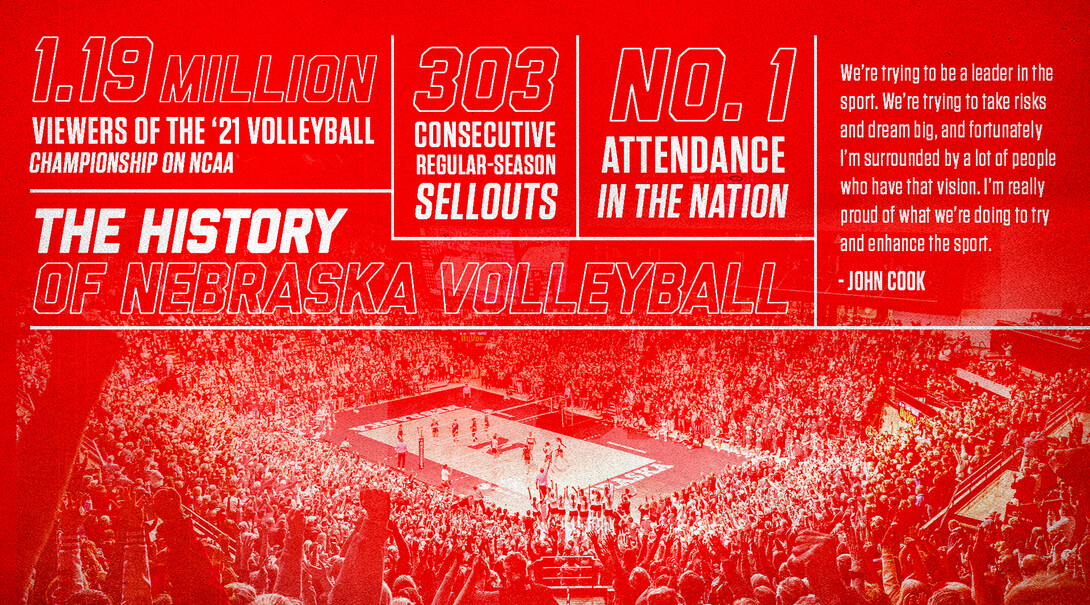

Husker volleyball is one of the most televised Division I volleyball teams in the country. In the 2021 regular season, 20 of 30 matches were televised. Nebraskans watch more volleyball on TV than any other college volleyball program.

“What really changed was when we started televising matches on any team in the state,” Cook said. “That gave a lot of girls like the Jordan Larsons, Lindsay Krauses to the Kelly Hunters, Kadie and Amber Rolfzen, just a great visual of examples and role models for them to aspire to be.”

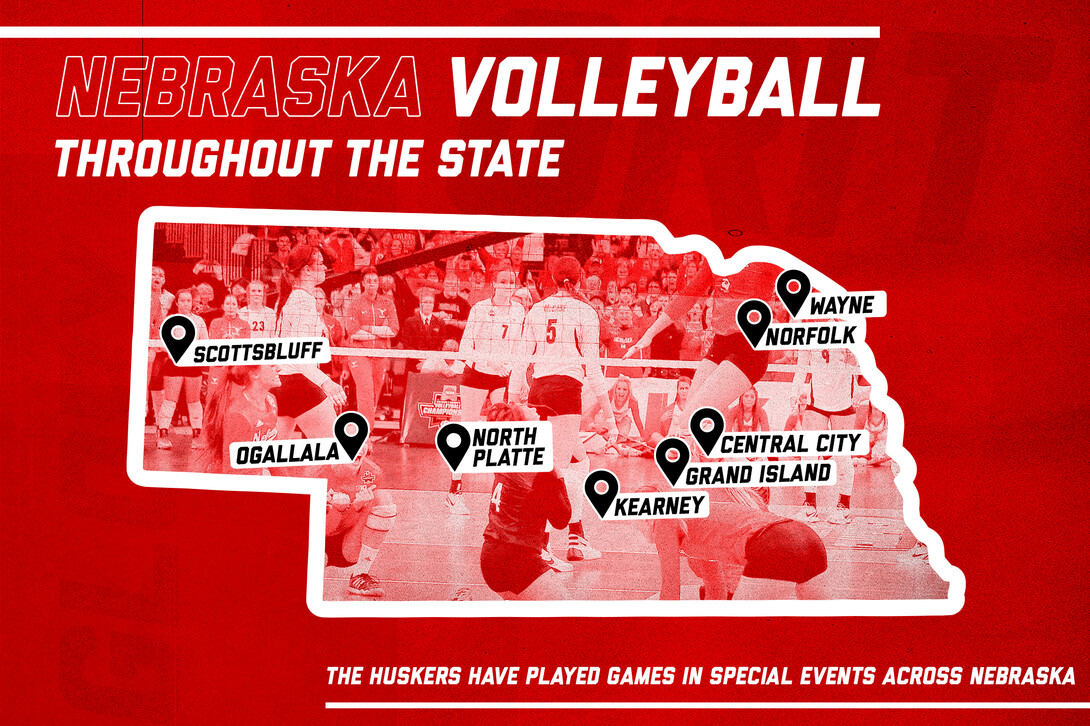

Because Huskers volleyball’s home matches are always sold out, Cook and his Huskers play the spring game in different towns across the state to share Nebraska volleyball. It’s a huge deal, he said, for the girls in the state to have role models and see high-level volleyball often.

“We get in trouble because there are not enough tickets when we’re playing in a smaller gym,” he said. “But again, I think this helps build the statement about Nebraska volleyball being a state treasure — that we share it with everywhere in the state and not just in Lincoln.”

Volleyball has never been bigger

To celebrate the impact of volleyball on the Cornhusker State, the Nebraska volleyball program will host the University of Nebraska at Omaha at 7 p.m. Aug. 30 in Memorial Stadium. The game is part of a doubleheader that will feature a 4:30 p.m. exhibition between the University of Nebraska at Kearney and Wayne State College.

The celebration is expected to break NCAA volleyball attendance records. The largest-ever crowd for an NCAA volleyball match is 18,755 when Nebraska played Wisconsin on Dec. 18, 2021 in the NCAA Final at Nationwide Arena in Columbus, Ohio. The largest NCAA regular-season crowd is 16,833, a mark set when Wisconsin hosted Florida on Sept. 16, 2022.

“It’s pretty surreal that this is all happening,” Cook said. “We are dreaming big — and I think it’s going to be a really special day.”