Glucose test strips are essential for diabetics or anyone who needs to monitor blood sugar levels. The small, paper-based strips are inexpensive to produce and invaluable for health improvement. They save lives.

As useful as they are, though, the strips’ application is narrow. What if this cost-effective, convenient technology could be adapted to measure other particles as well — contaminants, pathogens, chemical agents and more?

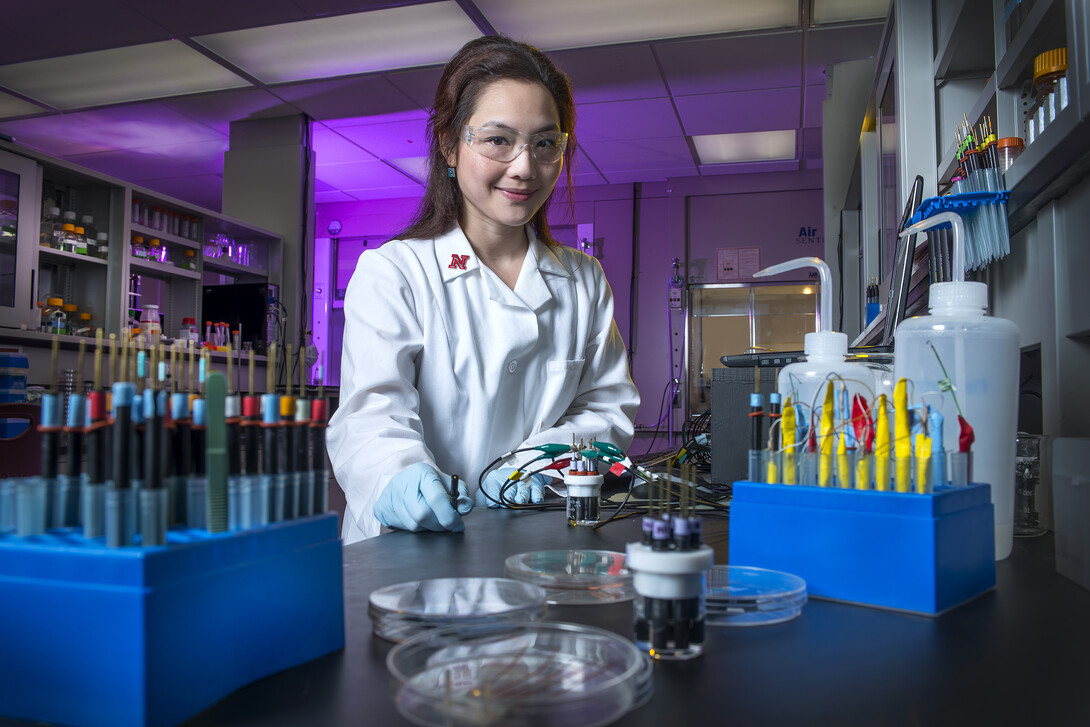

That’s exactly what Rebecca Lai, professor of chemistry at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, and her team are developing — versatile sensors for detecting a wide range of materials of a wide range of microscopic sizes, from incredibly small metal ions to larger particles such as spores.

“We’re using the same design principle behind glucose test strips to look for other targets — biological agents like botulinum, drinking water contaminants like mercury and many others,” Lai said. “Think about the impact of nitrate, for example—a big contaminant, especially in agricultural regions. To mitigate nitrate in water, we first must detect it.”

But it’s not enough to create a sensor that detects particles. It must be practical, affordable and easily used in the field.

“On a paper-based substrate, the cost of one sensor can come down to one dollar,” Lai said. “It’s cheap and portable. Those are the reasons the glucose sensor has been the most successful biosensor since the 1950s and 60s.”

Lai became familiar with glucose test strips when she was young — her mother was diabetic. But biochemistry wasn’t initially a field she considered. Her original career path was fashion design.

“I know, it’s a big change,” Lai said with a laugh. “I switched to biochemistry after I met my research adviser at California State University. I was taking general chemistry. I did well and wanted to see what was next. I realized that in doing research, I could do things that have never been done before. As an experimentalist, you get to be the first person to discover a reaction and see it work. That has always been very exciting to me.”

She may have abandoned fashion as a career, but Lai still puts her creativity to work in the laboratory. For example, she developed a science outreach program for elementary and middle school students, tying scientific concepts to moments from Harry Potter books. As a NU professor, she also enjoys merging these worlds for the undergraduate and graduate students she works with and mentors.

Aimee Ketner, deputy director for chemical and biological defense programs at the National Strategic Research Institute at the University of Nebraska, collaborates with Lai on a variety of projects.

“Lai’s passion for the work she is doing at the university is infectious,” Ketner said. “Her dedication to applying her expertise to developing next-generation detection technologies and her very strong work ethic are strengths that I see as key drivers towards success in this mission space.”

The working environment at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln naturally catalyzes a collaborative spirit, Lai said.

“I’ve been collaborating with researchers in physics and engineering almost since I first arrived in 2008,” she said. “Of course, I need to be very good in my own field, but I learn so much through collaboration. I see STEM fields becoming more and more collaborative over time.”

Supporting this kind of collaboration is one of the main objectives of NSRI, which operates as the University of Nebraska System’s University Affiliated Research Center designated by the Department of Defense and sponsored by U.S. Strategic Command. Through NSRI, University of Nebraska experts can contribute their capabilities and capacity to solve national security challenges across the threat spectrum.

Throughout the next decade, Lai’s capabilities across fundamental and applied aspects of biosensors, especially in terms of the design and fabrication of folding- and dynamics-based electrochemical biosensors, will be vitally important to NSRI’s mission.

“There will always be new things popping up that people create to harm others or the environment,” Lai said. “We need a technology flexible and cost-effective enough to respond to emergent targets, so we can develop new sensors and create mitigation plans quickly.”

Lai’s passion for chemistry, enhanced by her resourcefulness and creativity, are clear gains not only for general health but for the defense of America.