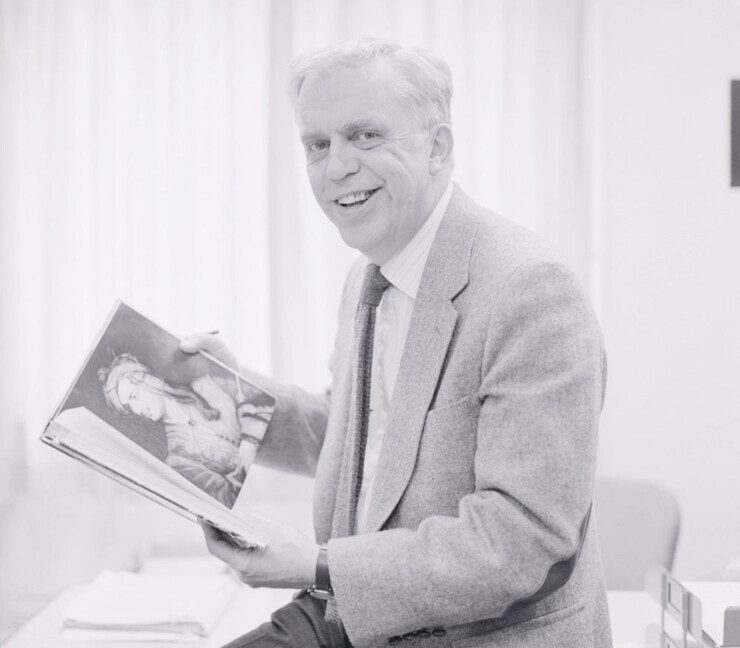

Even 53 years later, Huskers couldn’t but marvel at the vision and will that Louis Crompton summoned on behalf of a community which, throughout the University of Nebraska–Lincoln and much of America, was only just shimmering into view.

Appreciation, admiration and awe suffused the words spoken June 20 in honor of Crompton, the late, openly gay professor of English who, in 1970, taught the United States’ first full-fledged, for-credit course on LGBTQ studies.

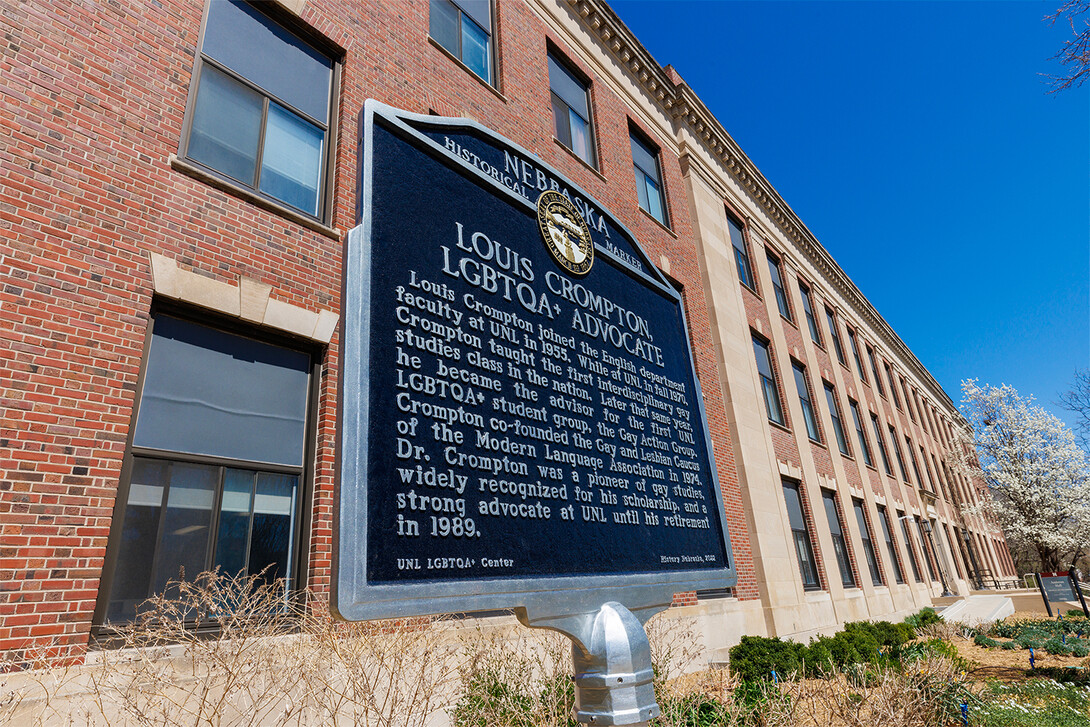

One first, his colleagues and friends decided, more than deserved another. And so, in partnership with History Nebraska, the university formally unveiled a Nebraska State Historical Marker in commemoration of Crompton.

“I think it’s an awesome moment in the history of Nebraska,” said Corrie Svehla, who chairs the Chancellor’s Commission on the Status of Gender and Sexual Identity. “What more can you ask for than to be on a university campus — the most diverse and inclusive environment in the state?”

Chancellor Ronnie Green described Svehla as a “champion” of establishing the marker, which stands at the south face of Andrews Hall.

The marker’s words were crafted in part by Timothy Schaffert, Susan J. Rosowski Professor of English and the director of creative writing at Nebraska. On learning about the proposal to establish the marker, Schaffert took it on himself to learn as much as he could about Crompton’s pioneering course, Proseminar in Homophile Studies. Schaffert’s research helped clarify the historic status of the course, which Crompton himself had downplayed.

“Homosexuality study at the time was done by outsiders looking in,” Schaffert said at the unveiling. “It involved a magnifying glass. It involved The Other. ‘Homosexual: friend or foe?’

“So I think that this particular extraordinary act — offering this course that had to go against laws, against powerful voices of repression, against historical prejudice — is more than just a course, more than a rebellion. It was an act of compassion, a gesture of humanity and humanization. When we’re thrown a lifeline, we’re able to throw that lifeline to others, and they can use those lifelines to throw to others. I think that’s what this course was: It was a mode of communication. It was an alert. It was a signal. It was a voice. And I think it just demonstrates … that through these gestures, you can establish a legacy of rescue.”

Pat Tetreault met Crompton and his partner, Luis Diaz-Perdomo, in 1992, after taking a job with the University Health Center and joining what was then known as the Committee on GLBT Concerns. Tetreault recalled how Crompton and Diaz-Perdomo opened their home to host a support group for gay men, one that the duo kept going until Diaz-Perdomo’s retirement. And she remembered the many reports that Crompton co-authored and submitted to university leadership as part of his efforts to foreground LGBTQ-relevant issues: “Don’t Ask, Don’t Tell,” benefits for the partners of gay employees, and the HIV/AIDS crisis.

Those efforts, she said, have continued to echo and reflect across the university since Crompton’s passing in 2009.

“It was a different time, then, when our community had much less visibility, and there were often negative consequences for living openly or being out in some way,” said Tetreault, director of the university’s LGBTQA+ Center and the Women’s Center. “Not that those things still don’t exist — just at a very different level. And Lou’s willingness to be visible and to advocate for inclusive education, programs, services and scholarships helped pave the way for much of the progress we see today.

“We may have heard the saying that we stand on the shoulders of giants. Lou’s are one of those sets of shoulders that we stand on, that help continue to provide support.”

For all of Crompton’s contributions to the Husker community, his willingness and ability to introduce a gay studies course just a year after the Stonewall uprising — the seminal event of LGBTQ civil rights in the United States — remains “mind-boggling” to Svehla. The lessons taught via that course, he said, could never be confined to a 1970s classroom.

“I think he’s shown that everything is open to discuss. There shouldn’t be a limit on what we’re talking about,” Svehla said. “We may disagree, but we should be researching and talking about why things are this way, or why that way, and get a better understanding of each other.

“We’re just pushing forward and maintaining that community. We just want everybody on campus to be accepted for who they are.”