It’s a perennial headline — long wait times at election voting sites.

A team of engineers and political scientists, including University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s Jennifer Lather, is conducting research with the University of Rhode Island VOTES project to combat the problem. The goal of the project is to make voting a more efficient and positive experience by optimizing layouts and resource allocation at polling sites.

Lather, assistant professor of architectural engineering, said the team has been collecting data at polling sites during elections since 2017. Their findings and resulting toolkits and recommendations have been implemented at polling sites in Rhode Island, California, New Jersey, Michigan and Pennsylvania.

For example, a forthcoming study from the project highlights how separating the processing of provisional voters at check-in can result in a significant reduction in the amount of time voters spend in a voting center, yet that recommendation changes when adding COVID-19 restrictions.

“The data we have helps us inform the operations of election days,” Lather said. “That’s essential to making sure that people have a good experience when they come to the polls, and that they feel encouraged to exercise the right to vote.

“Additionally, when COVID-19 hit, we started quickly adapting the tools we had been making to include COVID-19 mitigation strategies in order to help election administrators understand how social distancing, sanitization, and layout would impact their flow of operations when people come to the polls.”

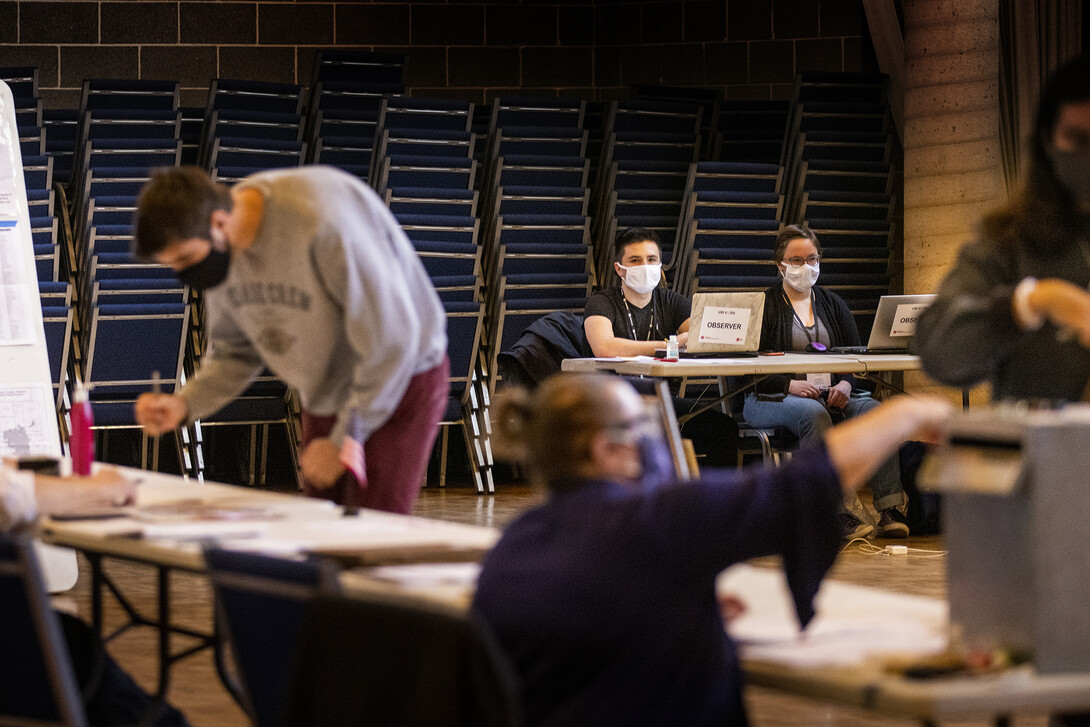

Lather joined the VOTES project in 2019, and gathered new voting data in Nebraska this year by partnering with the university’s Bureau of Sociological Research. She and staff from BOSR trained 30 observers — many undergraduates in political science and sociology — who fanned out at 15 polling sites in Lancaster and Douglas counties Nov. 3. The observers collected data such as voter arrival times throughout the day, the time spent at check-in, and the time spent completing the ballot and turning it in.

“Our observers will be timing stations, not people,” Lather said. “We’re trying to get a sense of throughput, understanding how long it takes to do check-in, when someone starts marking their ballot and when does that end, which has a lot to do with how many things are on the ballot. Some people are going to take more time or take less time because they’ve already decided at home, and we want to capture the whole range of how long it takes someone to vote.”

Lindsey Witt-Swanson, associate director of BOSR, said the partnership is one of the largest observational projects ever conducted by the Nebraska-based research bureau.

“Collecting all of the data in one day is certainly an added challenge, not to mention the need for precautions because of the COVID pandemic,” Witt-Swanson said. “We are pleased that we have been able to hire sociology and political science students for the day to cover our labor force needs while also giving them research experience on a unique project.

“Even better, we get to be involved reaching toward a goal everyone can agree on: shorter voting lines.”

Nebraska presented a new opportunity for data collection for researchers because of its urban and rural mix, and its paper balloting system, which is unlike other voting systems where data was previously collected.

“A lot of places have systems similar to Nebraska, and we want to understand those nuances among all voting options, to hopefully reduce lines in many different places,” Lather said.

The pandemic also provided a unique data set, and this specific collection was funded by the Democracy Fund and the Stanford-MIT Healthy Elections Project.

“COVID-19 has provided more incentive to collect and analyze this data to understand layout, flow, and space in new ways,” Lather said. “The interplay between circulation, layout and operations can create a complex model in what seems like a relatively simple system, thus we are working to develop new models, which will be verified and validated based on election day observations and data.

“Even though this data will be unique to the political environment and the pandemic conditions, our methods will be translatable. We expect the work will be able to provide a basis for new model types which are able to address layout, flow, and resources.”

The project will continue in Nebraska, as plans are being made to observe polling sites during the next primary and general election. More information about the team, the project and their tools can be found at the URI VOTES website.