To paraphrase the song, these milkshakes bring all the boys, and girls, to the lab — where scientists will get a glimpse of their brains’ reactions to that first delicious sip. Is it characterized by calm self-regulation — or overexcitement?

Nebraska researchers will use this and other data as they study factors that affect adolescent and young adult health, with an eye toward finding intervention strategies to head off obesity, one of the nation’s most pernicious health problems.

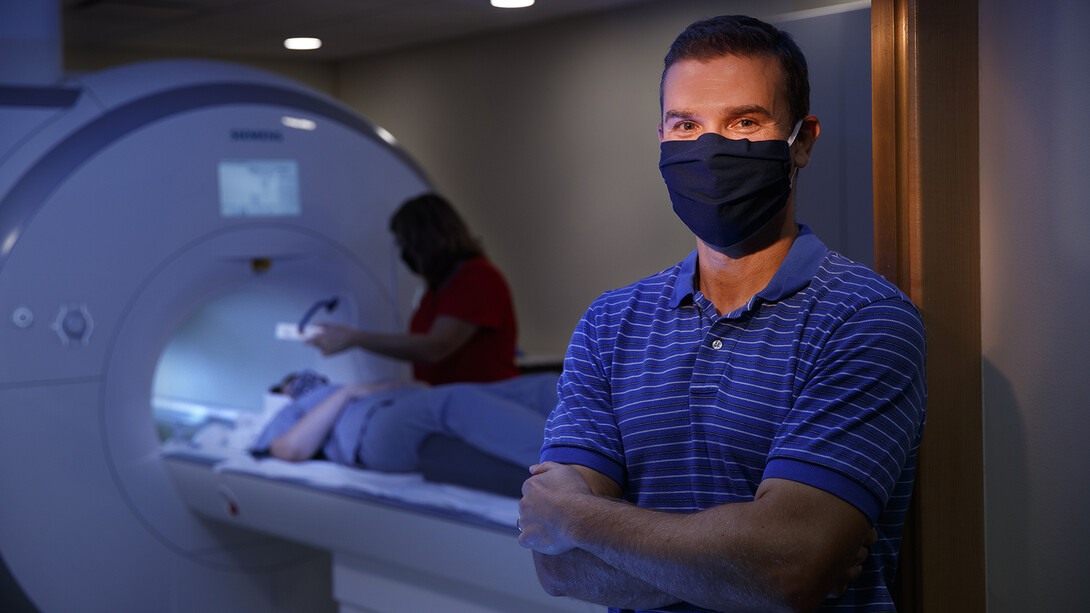

Timothy Nelson, professor of psychology at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, has received a five-year, $3 million grant from the National Institutes of Health’s National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases for this research. The project is conducted through the university’s Center for Brain, Biology and Behavior.

The research will focus on a longitudinal sample of about 300 young people in the Lincoln area whom Nebraska researchers have been studying since they were preschoolers; they’re now in their mid to late teens.

At the center of this decade-and-a-half-long research is executive control, the brain’s ability to direct attention and behavior. It allows people to hold information in their minds and use it, shift between different tasks and inhibit urges, among other things. Deficits in executive control have been shown to contribute to disruptive behavioral problems and poor academic achievement in children.

The Nebraska research is focusing on the link between executive control and risky health behaviors that may cause weight problems.

Executive control allows people to consistently avoid unhealthy snacks, get up and move even when they don’t want to and go to bed on time, Nelson said. It’s also critical to breaking bad habits and finding ways around challenges that hinder reaching goals, such as a lack of nearby grocery stores or finding time for physical activity.

“Broadly, we’re finding that executive control abilities as early as preschool can influence a wide range of important outcomes in both mental and physical health,” said Nelson, a clinical child psychologist by training. “We’re getting more and more clues that executive control might be a really important contributor to later health development.”

Executive control develops rapidly during preschool years but continues through adolescence and even well into people’s 20s, Nelson said.

“With such a protracted developmental course, there are various points at which we can intervene and potentially affect health outcomes,” he said.

Adolescents typically are making increasingly adult decisions that can have major implications on their long-term health, but their executive control abilities may not be mature enough to make and enact well-informed decisions consistently.

Researchers believe they can come up with ways to train executive control to help young people make better decisions.

“What are the most promising intervention targets, and at what points in development are they most important?” Nelson said.

The new research will use MRI technology at the Center for Brain, Biology and Behavior.

That’s where the milkshakes come in.

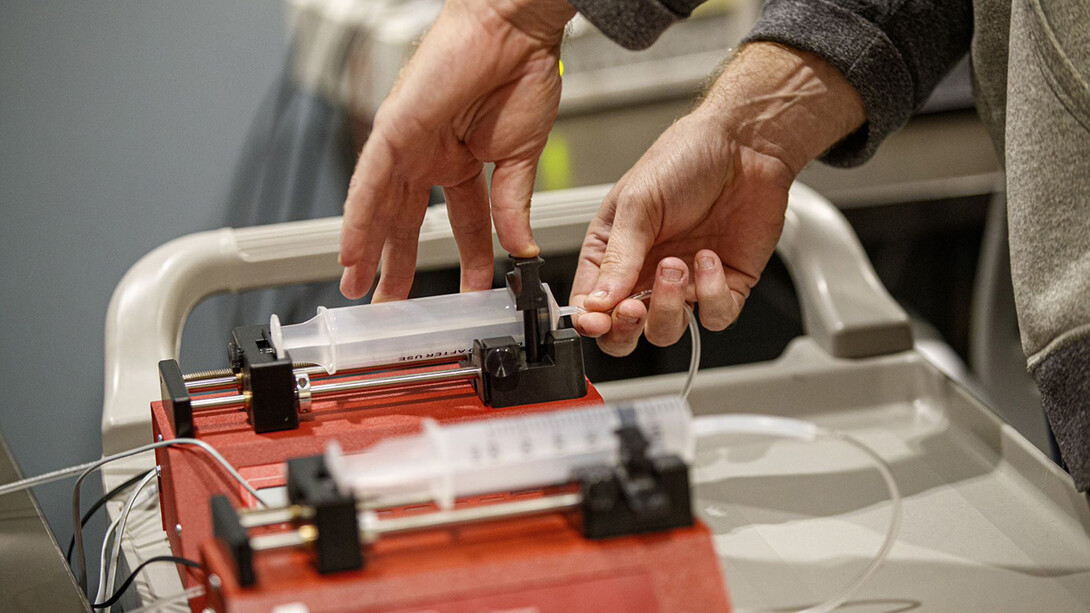

Cary Savage, director of the center and a principal investigator on the project, said new equipment now being tested will use a syringe that delivers milkshake to subjects while they’re in a special scanner. Subjects will be given a cue to take a sip, then a cue to swallow. The MRI scanner will measure the brain’s activity during this process.

“Our primary hypothesis is that young adults with a history of poorer executive control will have a stronger response to the milkshake than those with stronger executive control abilities,” Savage said.

“We’ll be trying to connect those reactions back to their cognitive performances in preschool,” he added.

Researchers also are studying self-regulation, tracking brain activity as subjects look at pictures of appealing food and imagine eating it but then think about the potential consequences of eating it, Savage said.

Nelson said subjects will be asked to down-regulate their responses, to exercise self-control.

“Individuals differ greatly in how well they can do that,” he said. “In the scanner, we can capture the neural activity patterns. We’re going to get these really interesting neural measures of response to food.”

Savage said researchers are trying to determine which comes first — whether a person’s cognitive function predisposes them to choices that lead to obesity, or whether diet choices and a lack of exercise affect their cognitive functions. It’s likely some of both, and having 15-plus years of research on subjects will help determine that.

“Now we have this opportunity to scan 19-year-olds for whom we have all this data. This is the clearest opportunity yet” to answer some of those questions, said Savage, a professor of psychology and Mildred Francis Thompson Professor of social sciences.

The new research will build on previous studies, begun at Nebraska by Kimberly Espy, who is now at the University of Texas at San Antonio but is still involved in the Nebraska work, and continued by Nelson’s team.

Those include studies of how behavioral and environmental factors affect susceptibility to obesity, which can lead to a number of health complications, including diabetes, heart disease and some cancers. For example, Husker researchers have mapped the food and exercise options throughout Lincoln so they can determine the environments of the various neighborhoods where their 300 subjects live.

“Essentially what we’re doing is looking to leverage the very rich data that we’ve collected from this sample since preschool,” Nelson said.

“That’s the most innovative aspect” of the university’s research, Nelson said. It combines developmental, cognitive and environmental science to get at answers.

“Those are robust areas of obesity research but they’re very rarely combined,” he said.

In addition to Espy, Nelson and Savage, the team includes Jennifer Nelson, research associate professor of psychology and director of research strategy and infrastructure in the Office of Research and Economic Development; Becca Brock, associate professor of psychology; Doug Schultz, research assistant professor; and the University of Nebraska Medical Center’s Jennie Hill, associate professor of epidemiology, and Amy Yaroch, professor of health promotion, social and behavioral health.