The University of Nebraska–Lincoln is joining a new $27.4 million global initiative to reduce methane emissions from livestock by harnessing natural variation in how animals digest food. Backed by the Bezos Earth Fund and the Global Methane Hub, the effort will support research and breeding programs to identify and scale climate-efficient livestock across North America, South America, Europe, Africa and Oceania.

“This initiative is a cornerstone of a broader global push to accelerate public-good research on enteric methane,” said Hayden Montgomery, agriculture program director at the Global Methane Hub. “Together with the Bezos Earth Fund, as part of the Enteric Fermentation R&D Accelerator, we’re building an open, coordinated foundation that spans countries, breeds and species — delivering practical solutions that reduce emissions and support farmers worldwide.”

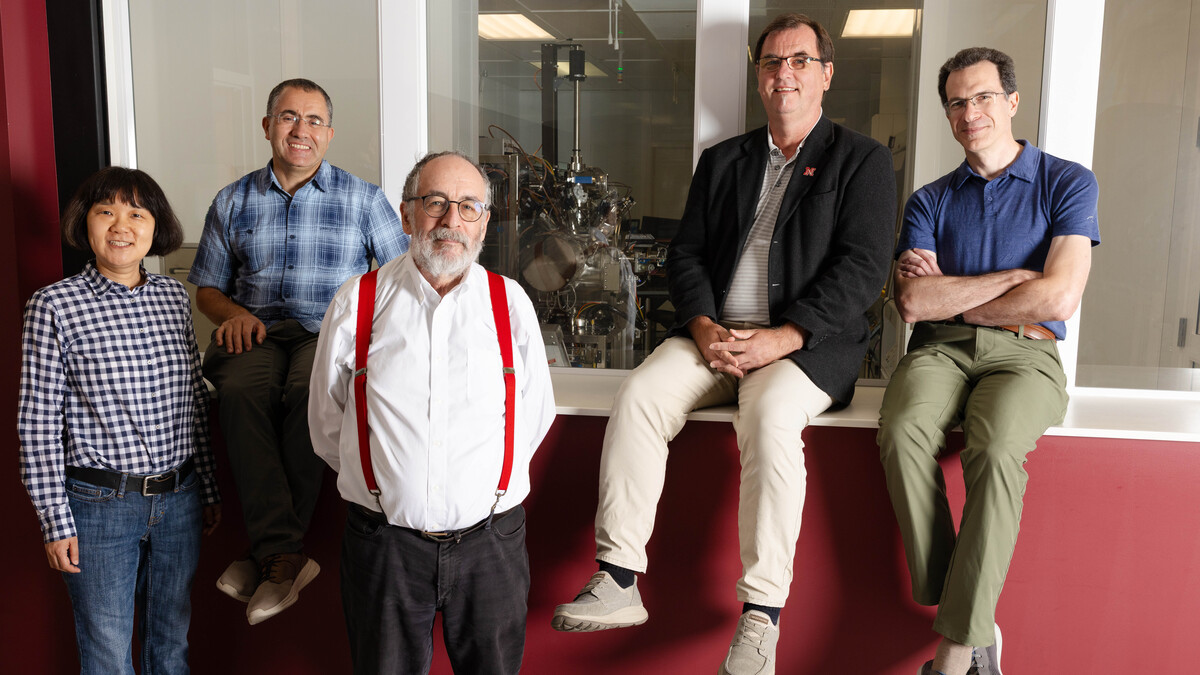

The University of Nebraska–Lincoln team, led by Matt Spangler, Ronnie Green Professor of Animal Science, will focus on collecting and analyzing methane data from beef cattle to better understand the role genetics plays in methane production and its relationship with traits of economic importance to cattle producers. Researchers hope the effort will lead to tools that inform genetic selection decisions by beef producers.

The $2.34 million project taking place at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln is in addition to two other major research efforts at the university aimed at reducing methane emissions in livestock.

A $5 million U.S. Department of Agriculture-funded project led by Paul Kononoff, professor of animal science, brings together Husker faculty and researchers from the U.S. Meat Animal Research Center to explore how genetics, gut microbiome and nutrition influence methane production in cattle.

A second $5 million initiative, funded through the university’s Grand Challenges program and led by Galen Erickson, Nebraska Cattle Industry Professor of Animal Science, focuses on developing accurate, affordable methods to measure greenhouse gas emissions from grazing cattle. Both projects are focused on building practical tools and management practices that improve animal health, feed efficiency and profitability, while also improving sustainability in grazing systems.

The latest initiative is part of the Global Methane Genetics initiative — an international collaboration working to make methane efficiency a standard part of livestock breeding. The effort will screen more than 100,000 animals, collect methane emissions data and integrate findings into public and private breeding programs to deliver long-term, low-cost climate benefits.

“From a North American perspective, it is exciting to work with international colleagues as we strive to improve the sustainability of the global beef industry utilizing state-of-the-art technologies,” Spangler said. “The opportunities for graduate student training through this effort will lead to scholars that are uniquely positioned as they enter the workforce.”

Methane is a potent greenhouse gas — more than 80 times as powerful as carbon dioxide over a 20-year period. Cattle are the largest contributors to livestock-related methane emissions. But even within the same herd, some animals naturally emit up to 30% less methane than others. Scientists say selecting and breeding for these lower-emitting animals — just as farmers have long done for milk yield or fertility — can lead to permanent reductions in climate impact.

“Reducing methane from cattle is one of the most elegant solutions we have to slow climate change,” said Andy Jarvis, director of the Future of Food program at the Bezos Earth Fund. “Thanks to collaboration with the Global Methane Hub, we’re backing an effort that uses age-old selection practices to identify and promote naturally low-emitting cattle — locking in climate benefits for generations to come.”

Because these traits are already present in existing herds, farmers will not need to change their feeding practices or invest in new infrastructure with this approach, making it easy to participate in climate solutions without disrupting daily operations.

“This work brings together the best of science, industry and the global breeding community to accelerate genetic improvement for methane efficiency worldwide,” said Roel Veerkamp, leader of the initiative at Wageningen University and Research. “It fits nicely with our mission … to explore the potential of nature to improve the quality of life.”

Over time, this approach could reduce methane emissions from cattle by 1% to 2% each year — adding up to a 30% reduction over the next two decades — without changing diets, infrastructure or productivity.