When scours, pink eye or respiratory disease strikes a cow-calf herd or feedlot pen, quick and accurate diagnosis of the culprit pathogen is key to containing the damage.

A new instrument has enabled veterinarians at the Nebraska Veterinary Diagnostic Center at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln to identify potentially deadly bacteria in a matter of minutes – compared to the days it once took to identify pathogens via lab culture.

The $250,000 instrument uses MALDI-TOF mass spectrometry, which stands for Matrix Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization-Time of Flight. Purchased at the urging of the Nebraska Cattlemen and the Nebraska Veterinary Medical Association, the device will be a centerpiece of the new $44.7 million veterinary lab now under construction on the university’s East Campus.

Approved by the Nebraska Legislature in 2012, the new diagnostic facility is expected to open June 1. Donors provided 10 percent of the facility cost; the rest will be paid with state bonds in the next 10 years.

As a sign of the future and of the university’s commitment to the region’s livestock and animal health industries, the MALDI-TOF already is an integral part of the center’s diagnostic procedures. It is used to diagnose ailments in pets and zoo animals, as well as livestock.

“The new MALDI-TOF in the Veterinary Diagnostic Center was purchased in order to provide our clients with new cutting-edge technology regarding identification of bacterial pathogens in a timely and accurate fashion,” said Alan Doster, director of the Veterinary Diagnostic Center.

With an infectious disease, every day matters for the animal and the herd, said Dustin Loy, faculty supervisor of bacteriology in the laboratory. Some pathogens, such as E. coli and Salmonella, can cross over species to cause human illnesses. Others have become antibiotic resistant, making quick identification even more critical. The wrong medication not only is ineffective – it could foster even more antibiotic-resistant strains.

“It makes our throughput faster and our capacity higher and we can get diagnoses faster,” Loy said. “Then we can treat faster and more appropriately, whether it’s choosing the right antibiotic or vaccine or some other intervention.”

For example, a 2014 case in which a shiga toxin-producing E.coli strain was found in a Nebraska feedlot relied on quick action and diagnosis. After observing bloody diarrhea among the heifer calves in the affected pen, the feedlot crew treated the animals for a parasitic infection. One animal was euthanized after displaying neurological symptoms. An immediate necropsy enabled university veterinarians to identify the E. coli infection, which appeared to be the first report in cattle of disease associated with that strain of E. coli.

Because that E. coli strain can cause human illness, the case led to a call for Nebraska veterinarians and livestock producers to watch for additional cases among cattle.

“Although we did not have the MALDI for this case, this type of situation underscores the impact diagnostics can have on potential public health issues,” Loy said. “If we had had the MALDI, we would have been able to get the information to the veterinarian and the producer even faster.”

Developed in Japan and awarded the Nobel Prize for chemistry in 2002, the MALDI-TOF technology previously was used mostly for research. Recent improvements in bioinformatics and software now allow it also to be used for clinical purposes. The instrument is becoming standard equipment in the top veterinary labs across the country. Loy said Nebraska is one of about 30 U.S. veterinary diagnostic laboratories that have the instrument. About 60 state and university animal diagnostic laboratories, including Nebraska’s, are part of the USDA’s National Animal Health Laboratory Network.

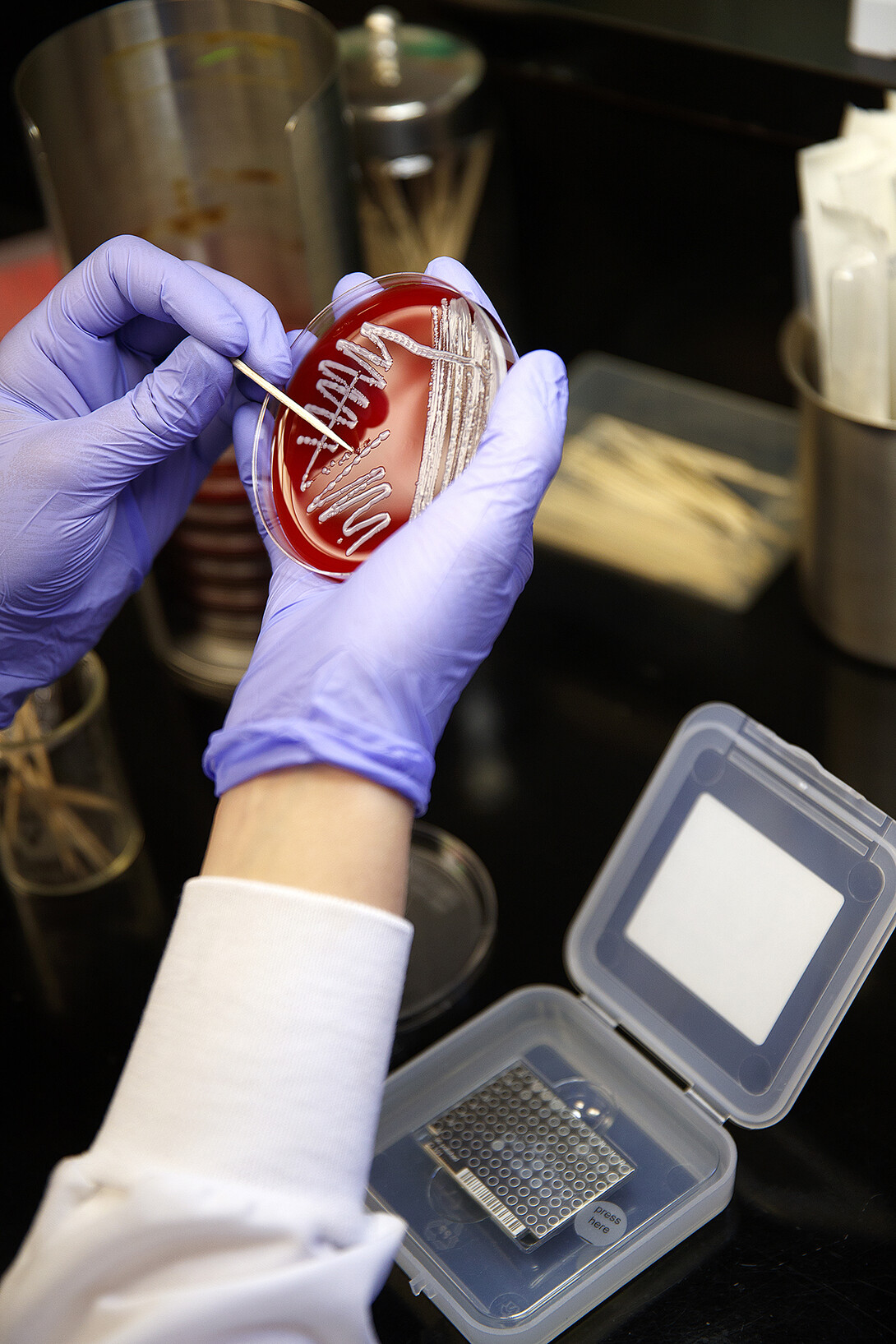

When an animal becomes ill, veterinarians working with livestock producers, pet owners and even zoos submit samples from blood, stool, swabs, bedding or tissue for bacterial culture to the diagnostic center. The MALDI-TOF instrument requires a bacterial sample only the size of a tip of a toothpick.

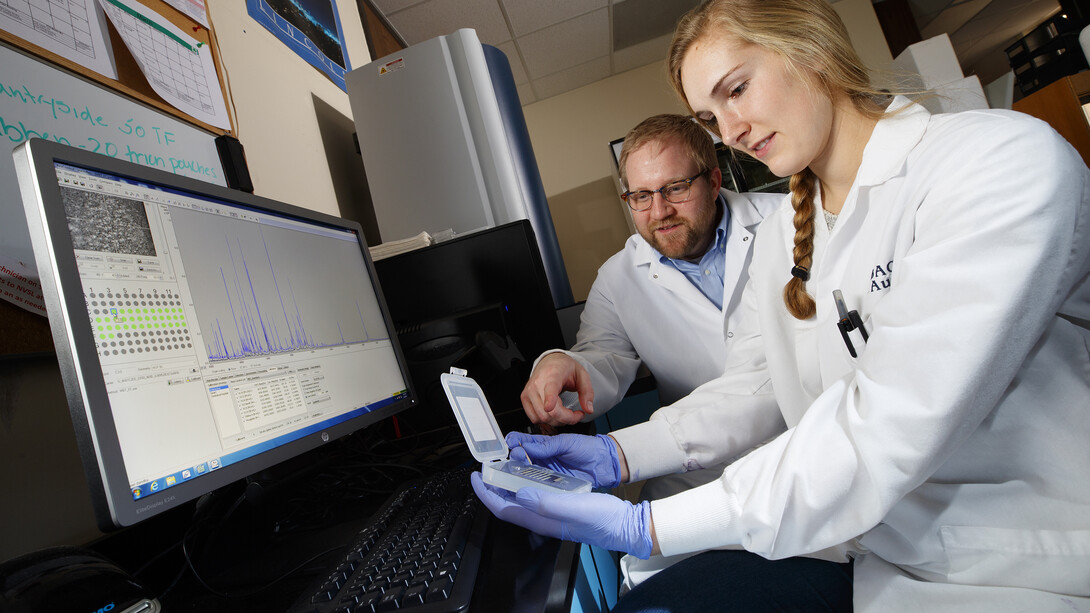

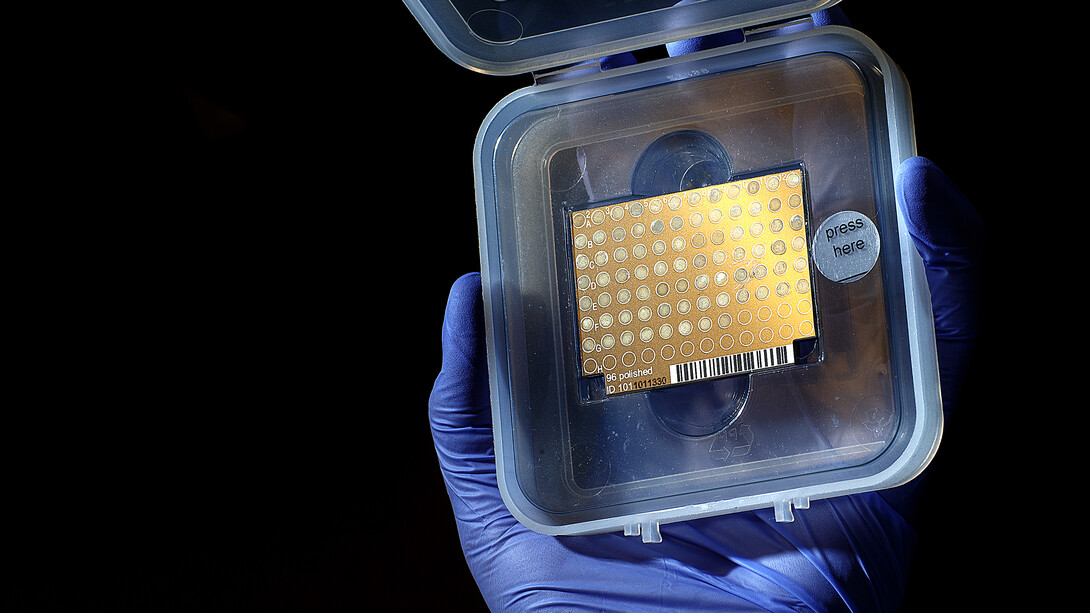

A matrix material is applied to the samples, which are inserted into the machine via a port. A laser heats the matrix, which causes a microexplosion that vaporizes the bacteria into ionized proteins. The proteins are identified by their mass and charge as they fly through a vacuum chamber and collide with a detector. Each species of bacterium has its own mass spectrum “fingerprint.” A nearby computer screen reveals the peaks, intensity and size of the spectra. The instrument has the capacity to compare and match with 7,000 reference strains of bacteria, Loy said, with Nebraska scientists constantly adding more to the database.

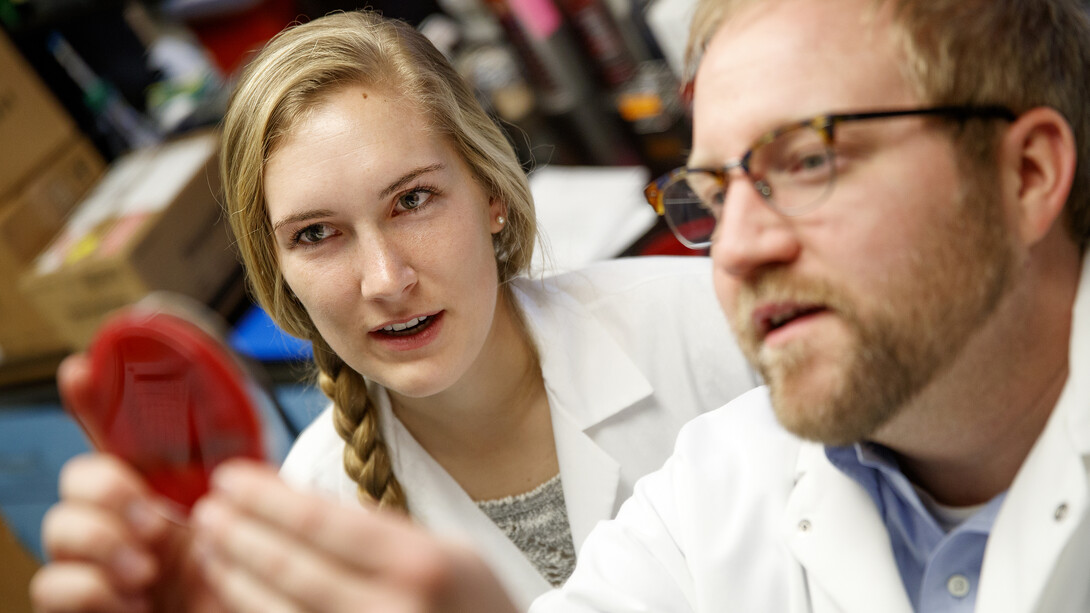

For example, Loy specializes in the study of pink eye and respiratory diseases found in calves. His undergraduate student, Kara Robbins, a pre-vet honors student from Brookings, South Dakota, is working to validate the method to identify a diverse collection of bacteria in the genus Moraxella, which cause pink eye, so that they can be accurately identified via MALDI-TOF.

Doster explained that the laboratory previously needed two to four days to use fermentation or media growth methods to culture a large enough sample of bacteria to identify it and to determine its antibiotic sensitivity.

Research now underway will develop methods to use the MALDI-TOF to determine which bacteria are more likely to be resistant to antibiotics or more pathogenic based on the specific proteins found in the individual bacteria.

The instrument represents a significant change for bacteriologists such as Loy.

“For me, professionally, it’s a paradigm change,” he said. “We’re moving from classic, test-tube biochemical testing and phenotyping to using a proteomics-based approach. It’s driven by computing capacity. This device can take large numbers of spectra and analyze them so quickly. The applications of this technology are just beginning.”