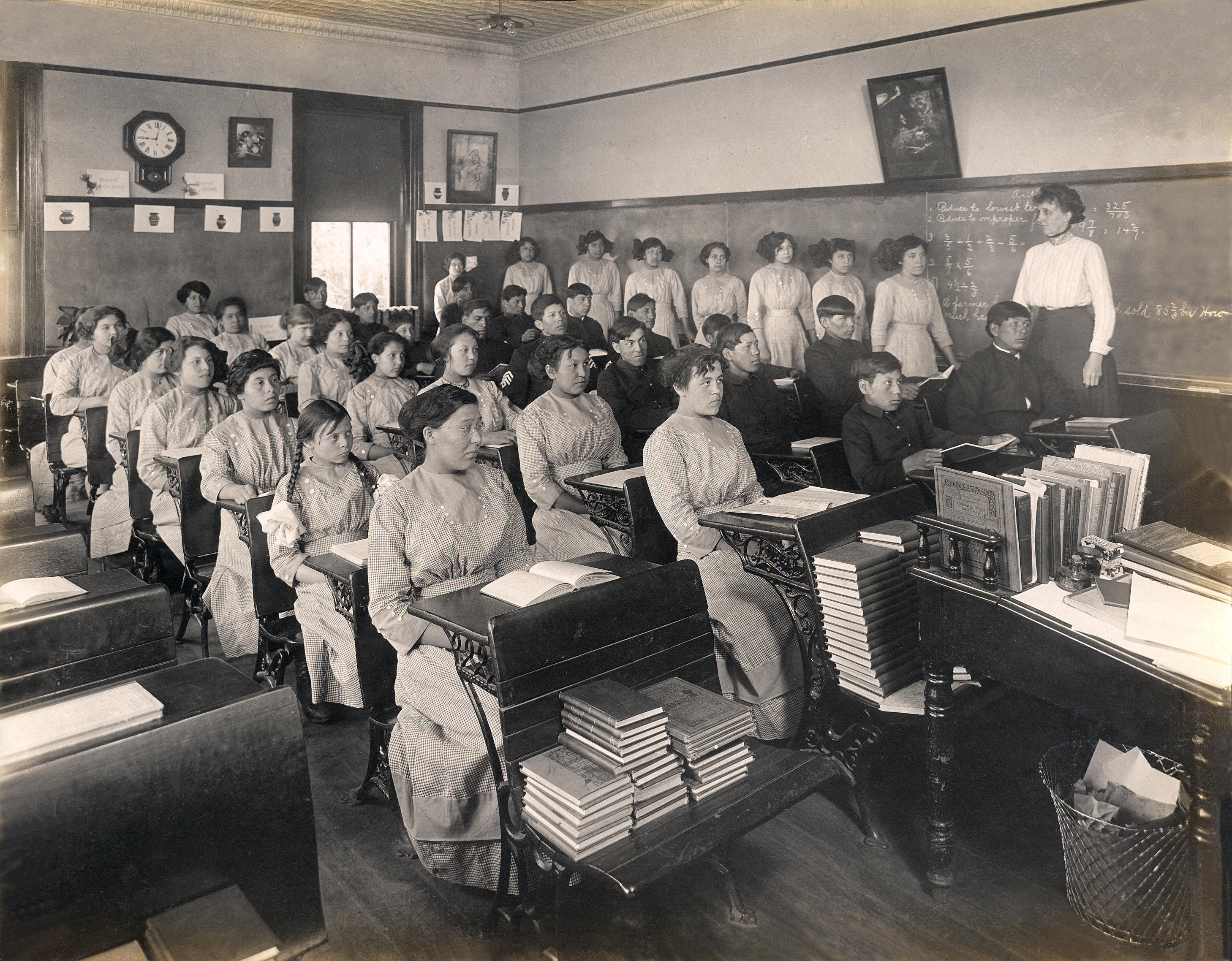

In the late 19th and early 20th centuries, the U.S. government sent tens of thousands of Native children to boarding schools in the hopes of assimilating them and breaking their ties to families and tribes. More than 300 schools were established for this purpose, including one in Genoa that grew to a 640-acre campus that enrolled thousands of children from more than 40 Indian nations during its 50 years of operation from 1884 to 1934.

The Genoa Indian School Digital Reconciliation Project is a new effort to tell the story of these children through record digitization, oral histories, community narratives and artifacts. The project is a collaboration between the University of Nebraska–Lincoln; Genoa U.S. Indian School Foundation; community advisers from the Omaha, Pawnee, Ponca, Santee Sioux and Winnebago tribes of Nebraska; and descendants of those who attended the school. It aims to bring greater awareness of the schools and their legacies while returning the histories of Native children from government repositories back to their families and tribes. So far, project members have digitized, described and published about 4,000 pages of documents from the National Archives in Denver and Kansas City. Communities and individuals will be able to contribute their own digital content to the record.

At Nebraska, the project co-directors are Margaret Jacobs, professor of history, and Elizabeth Lorang, associate professor in University Libraries. To ensure the project represents many perspectives and experiences of those who attended the school and their descendants, a council of Native community advisers provides direction and oversight. The advisory team is led by co-chairs Judi gaiashkibos (Ponca), executive director of the Nebraska Commission on Indian Affairs, and James Riding In (Pawnee), associate professor of American Indian Studies at Arizona State University. Other members include Everett Baxter (Omaha), Ben Crawford, Stuart Redwing (Santee) and Larry Wright Jr. (Ponca). Nancy Carlson of the Genoa U.S. Indian School Foundation also serves as a project adviser. Over its first two years, the project has employed three undergraduates and seven graduate students.

“The Genoa Indian School Digital Reconciliation Project offers public access through its website to thousands of documents and photographs. Through the power of documentation, the project tells the story of thousands of lives impacted over a 50-year period,” gaiashkibos said. “The documents that have been compiled tell the truth about a failed experiment in human cultural reprogramming. They speak for the children who were silenced, restoring their voices and those of their resilient descendants who carry on.”

Authorities designed the schools to “kill the Indian to save the man,” as Capt. Richard Henry Pratt, founder of Carlisle Indian School, put it. To assimilate Native children and break their tribal ties, most teachers and administrators forbade students from speaking their native languages and required Christian conversion. They formed students into military-style companies, which marched and drilled each day. Memoirs and oral histories of attendees reveal that boarding schools gave some children new opportunities and also subjected many to harsh discipline, abuse, exploitation and disease.

Support for the project is provided by the Council on Library and Information Resources, National Endowment for the Humanities and Nebraska’s College of Arts and Sciences, University Libraries and Center for Digital Research in the Humanities.

For more information on the project, click here or email genoadigitalproject@unl.edu.