Welcome to Pocket Science: a glimpse at recent research from Husker scientists and engineers. For those who want to quickly learn the “What,” “So what” and “Now what” of Husker research.

What?

Among its wide range of newfound freedoms, adolescence marks the first time that many teens gain at least some control over their diets. But the food choices of teens can stem from the eating habits they develop in early childhood — habits potentially influenced by individual traits.

One of those traits is executive control: the ability to focus, plan and then carry out intentions, even in the face of distractions or temptations. In the context of diet, poorer executive control might mean succumbing to the external cues and internal urges for sugary drinks or high-fat foods. And emerging research suggests that a child’s temperament — including their negative affectivity, or tendency to experience anger and anxiety — might contribute to emotional eating or other nutrition-eroding behaviors.

So what?

Nebraska’s Tim Nelson, Syracuse University’s Katherine Kidwell and colleagues wondered whether the effects of early executive control and temperament might carry over into adolescence. So the team conducted a longitudinal study with 313 preschoolers. At age 5, those children took part in a battery of tasks designed to measure their executive control, while their parents completed questionnaires about their children’s behavior. Years later, with the participants then between the ages of 14 and 18, the research team asked the adolescents to report their eating behaviors from the previous week.

When they did, the team found notable links between the childhood traits and the teenage diets. Children who showed poorer executive control tended, as teens, to drink more soda, eat more sweets and choose more processed, “convenience” foods, such as pizza. Negative affectivity in preschool corresponded with an adolescent preference for sugar-rich foods and beverages, too.

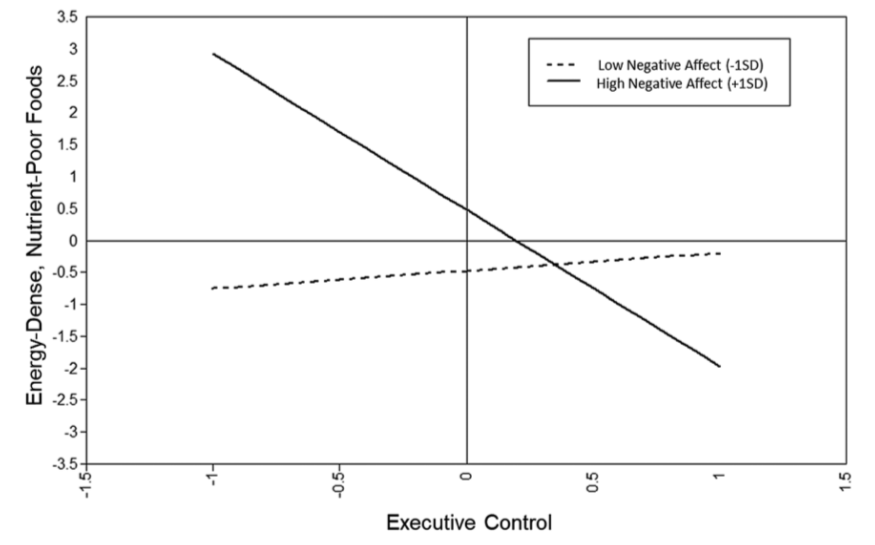

The links grew more complicated, and more interesting, when analyzing executive control and negative affectivity in tandem. Unsurprisingly, the teens whose younger selves were low in executive control and high in negative affectivity were the most likely of all to be consuming nutrition-poor foods. But those who countered their high negativity with high executive control ate healthier, suggesting that the latter may have helped compensate for the former.

Now what?

If preschooler traits can help predict eating habits even a decade later, they could also help identify children at long-term risk of developing Type 2 diabetes, obesity and other food-related health issues, the team said. Screening for executive control and temperament, in particular, might allow clinicians to target high-risk children for interventions before poor eating habits become entrenched.