Welcome to the Research Roundup: a collection of highlights from the latest Husker research and creative activity.

Fiber optics

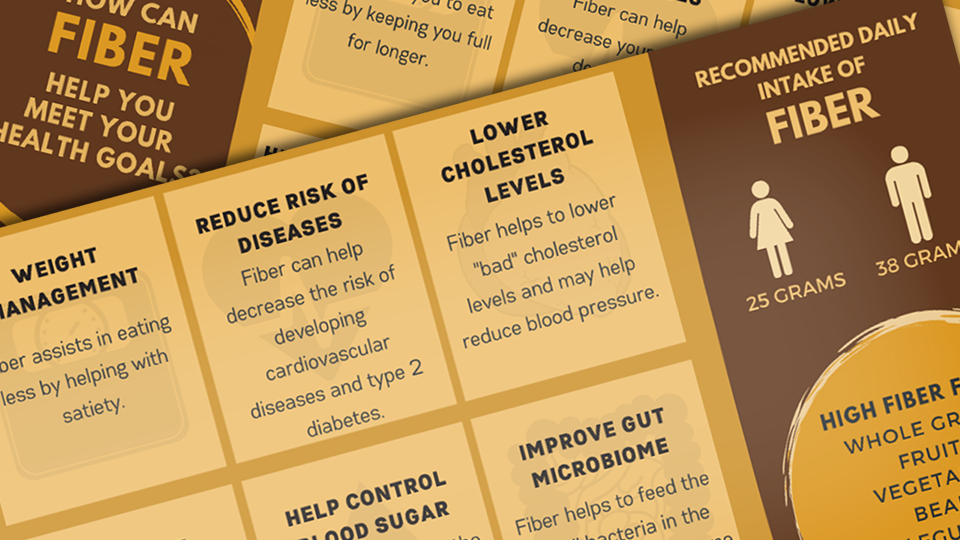

Though the benefits of eating fiber are legion — lower cholesterol, blood pressure and risk of colorectal cancer, a feeling of fullness that may curb calorie intake by up to 500 per day — Americans generally consume far less than they should. The U.S. Department of Agriculture and other agencies have employed multiple strategies to drive the purchase of high-fiber and otherwise nutritious foods, from offering prompts about their health benefits to subsidizing them for the sake of lowering prices. Still, empirical research on the usefulness of those strategies, especially amid the hubbub of crowded grocery stores, shelves and schedules, remains sparse.

The Department of Agricultural Economics’ Christopher Gustafson sought some clarity with the help of an online study that gave participants the chance to shop for 33 breads, 33 breakfast cereals and 33 types of crackers. A control group received neither information about the benefits of fiber nor any cost-saving subsidy. Other participants were offered either just a fiber-promoting prompt or only a subsidy-based discount: 10% on items considered a good source of fiber, 20% on foods deemed a great source of it. A fourth group, meanwhile, got both the informational prompt and the discounts.

When it came to the amount of per-serving fiber “purchased” by the participants, Gustafson found little difference between the control group and participants who were offered the subsidy-based discount alone. Participants receiving the informational prompt, by contrast, selected foods containing roughly 18% more fiber per serving than did the control group. But the group provided with both the prompt and the discounts chose most wisely of all, picking products with 30% more per-serving fiber. The prompt-only and prompt-plus-discount groups were more than twice as likely as the control group to consider the amount of fiber in products when shopping — with the benefit-focused prompt seeming to nudge them toward actually selecting high-fiber options.

Though the choices were only hypothetical, Gustafson said the study supports the promise of combining nutritional information, subsidies and well-timed prompts to make dietary fiber a more regular purchase.

After-school special

Ideally, assessments help instructors identify how well their students are grasping concepts without sapping too much of the time needed to teach those concepts in the first place. Choosing how and where to administer an assessment involves striking another balance: maximizing the effort students put into it while minimizing the incentive to rely on external resources that can misrepresent a student’s true level of understanding.

It’s little wonder, then, that educators and education researchers alike have varied both the types and settings of assessments in the hope of pinpointing the best combinations. The School of Biological Sciences’ Brian Couch and recent doctoral graduate Crystal Uminski have taken special interest in higher-stakes vs. lower-stakes assessments — the former scored according to correct answers, the latter on participation — and whether students take them inside vs. outside the classroom.

Couch and Uminski led a five-year study involving 1,578 undergraduate students taking an introductory course on molecular and cell biology. All students were administered some conceptual questions in the classroom and some outside it, with the stakes of the assessments alternating by year. The researchers discovered that students scored roughly the same on higher- and lower-stakes assessments when administered in the classroom.

But participants given lower-stakes assessments outside the classroom also scored about the same as the two in-classroom groups. Also promising? Other data indicated that students taking those participation-graded assessments outside the classroom tended not to rely on external resources that might otherwise skew scores and teacher perceptions of student learning. Collectively, the findings point to lower-stakes, out-of-class assessments as a viable alternative for teachers looking to optimize instruction time without sacrificing the validity of test results, the researchers said.

As for the students taking the higher-stakes, answer-graded assessments at home? They scored higher and spent more time answering questions than did their counterparts. Unfortunately, comparing those scores against traditional unit exams suggested that the students were spending that extra time consulting the internet or other shortcuts to arrive at their answers. Considering the unfair advantage such shortcuts might provide over some peers — and the possibility of inflated scores leading to overestimates of student learning — Couch and Uminski cautioned against raising the stakes when leaving students to their own devices.