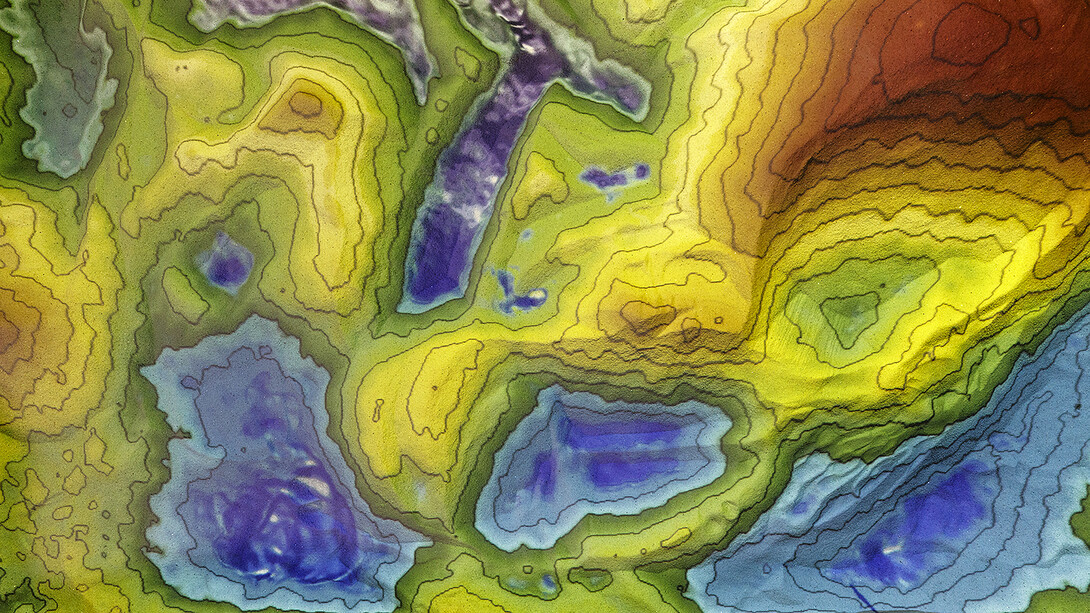

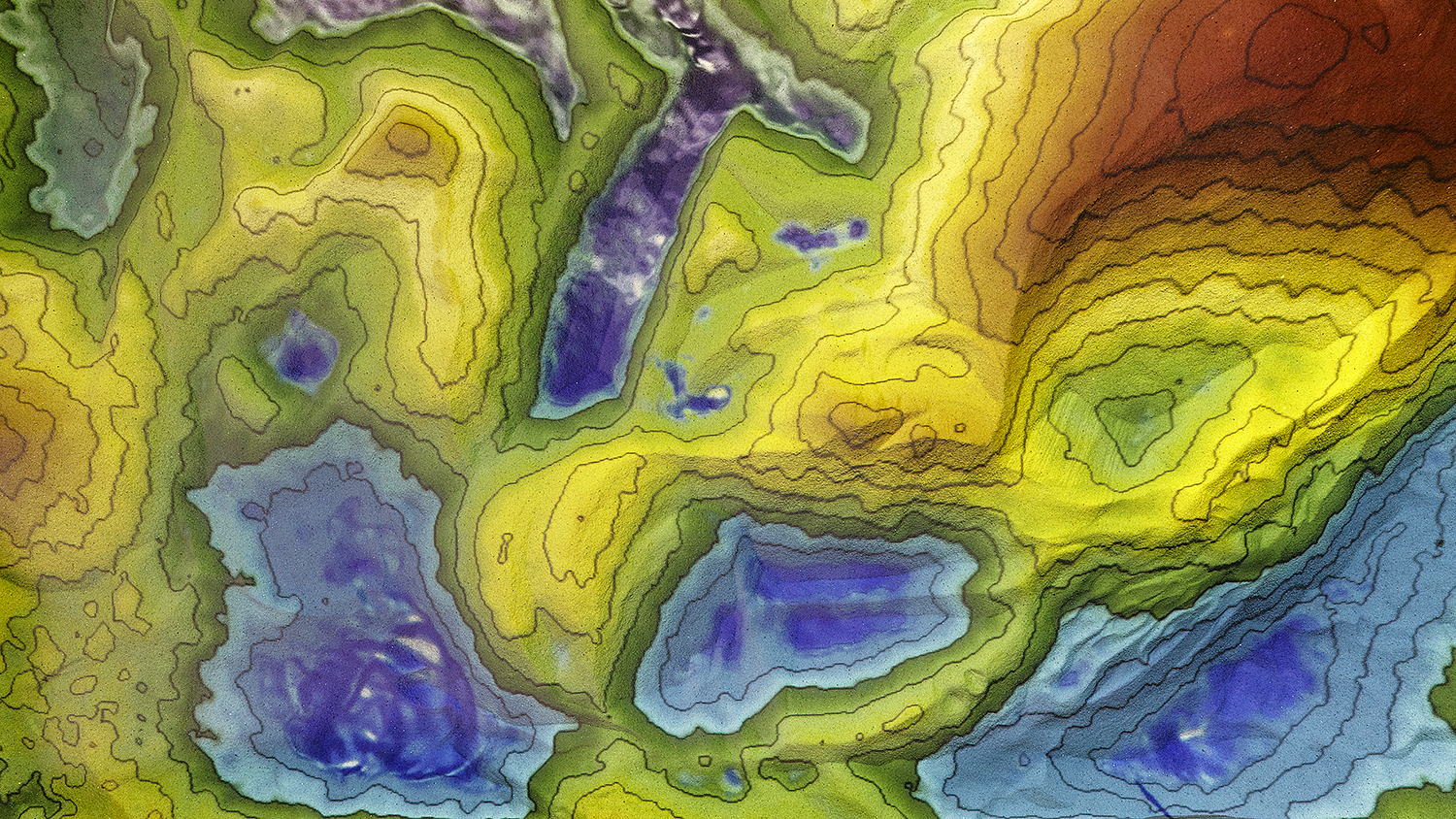

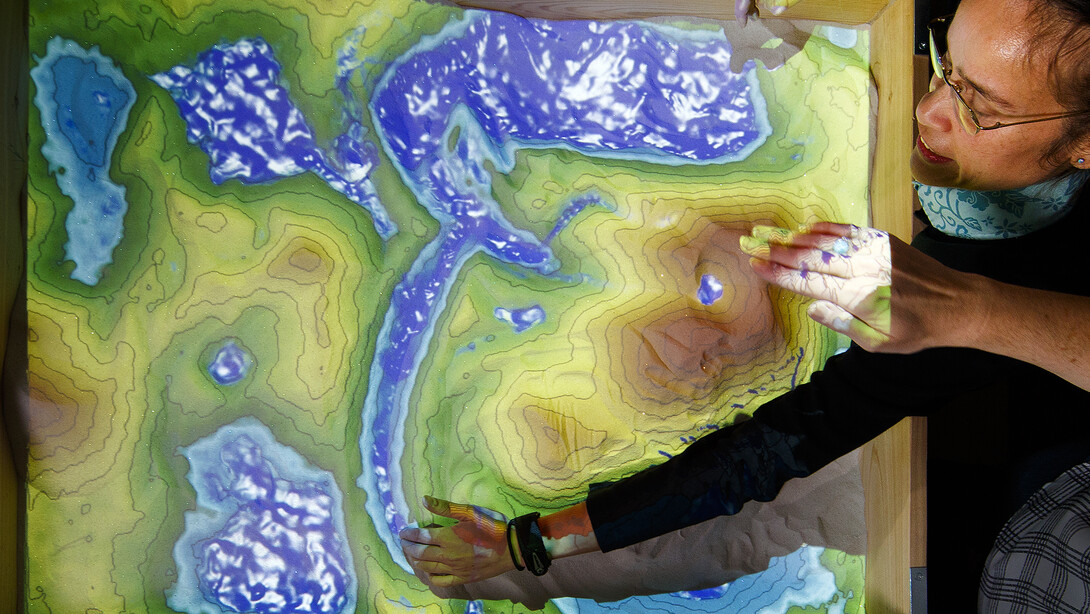

Narrow bands of red and orange, yellow and green ringed the hill of fine-grained sand as a projector shone down from its perch several feet above a cedar-sided box.

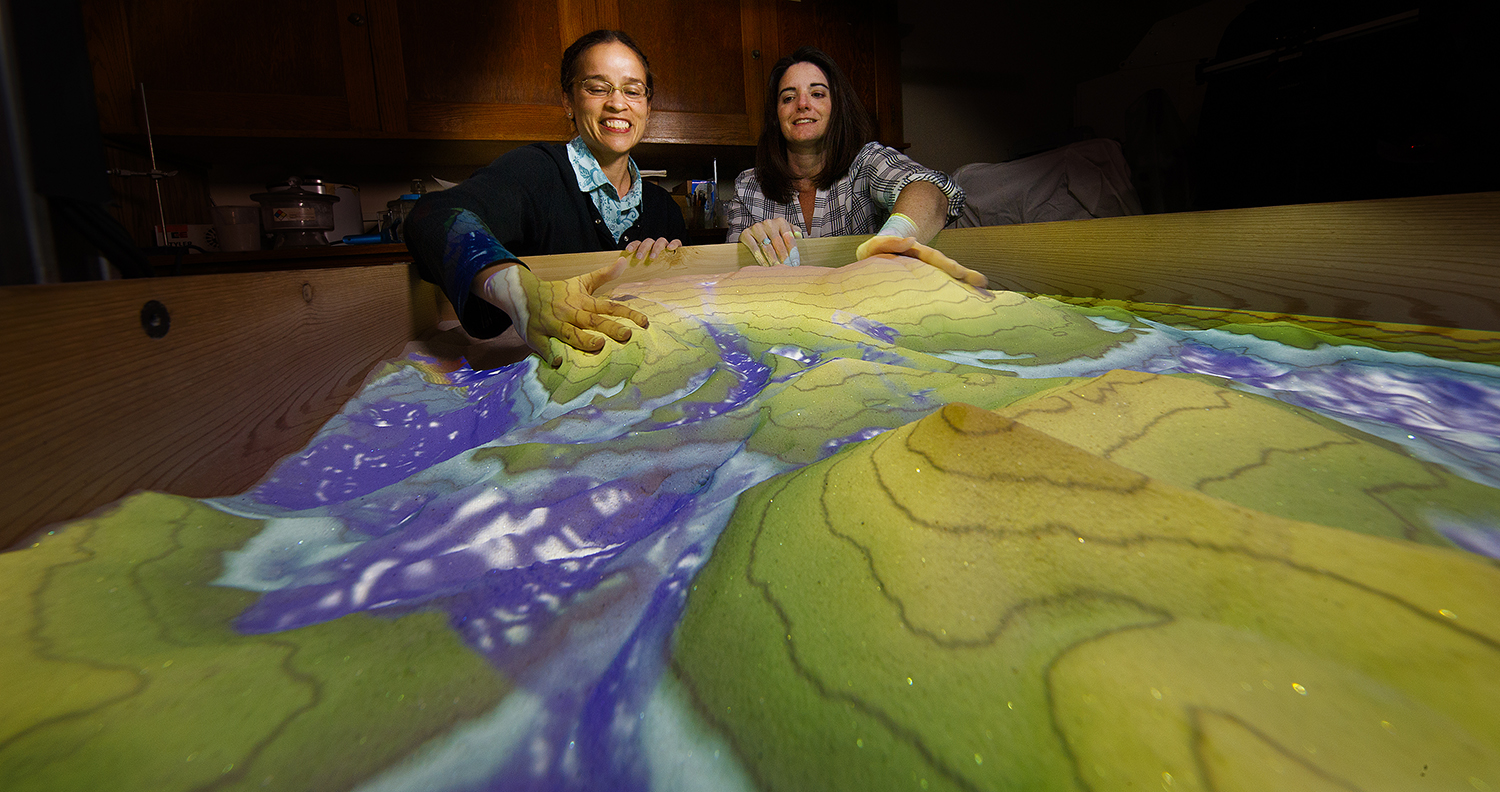

Tracy Frank scrubbed her palm over the ridge, flattening it. Each band’s color abruptly grew several tints lighter as the corresponding contour lines expanded and spread farther apart to illustrate the more gradual slope.

Using her index finger to scoop sand out of the crest, Frank cast her other hand in the role of a rain cloud that shadowed the newly formed crater. Water – or what looked like it – pooled in the impression, spilling over and cascading down the sides.

“It’s hard to pull people away from this,” she said, smiling.

That smile emerged while demonstrating the wonders of an augmented-reality sandbox that recently took up residence in Bessey Hall. With the support of alumni, the Department of Earth and Atmospheric Sciences built the sandbox to help students better understand geologic formations and mentally translate the landscapes normally depicted on 2-D topographic maps.

VIDEO: Augmented-reality sandbox gives students hands-on education – literally

“As geologists and meteorologists, we’re required to visualize things in three dimensions,” said Frank, professor and department chair. “Oftentimes, we’ll teach a class using topographic maps and then … find out that (students) didn’t quite get the concepts the way we thought they might. And we’re hoping that this might help cement (those) in.”

By registering elevation changes in real time and mimicking water flow over and around geologic features, the technology encourages active, inquiry-based learning in ways that a static map cannot, Frank said. Faculty in the department envision the sandbox becoming a cornerstone of undergraduate geology labs, outreach initiatives and research into how instructional technology shapes the learning experience.

It might even help senior geology majors hone their skills before heading to Wyoming for a six-week capstone course that asks them to map the state’s rugged landscapes.

“Sometimes that’s really difficult for them, especially if they’re in mountainous terrain for the first time,” Frank said. “Having the experience of working with the sandbox, being able to visualize things in that way, should help them when they’re out in the field using a standard map.”

Leilani Arthurs, assistant professor in the department, said only a few researchers have studied the educational impacts of augmented-reality sandboxes. With colleague Mindi Searls, Arthurs wants to examine whether the engagement and enthusiasm that the sandbox evokes in students can accelerate their ability to grasp spatial concepts inherent to geology.

“Not every department that teaches geoscience has one, so (Nebraska) is definitely … pushing the boundaries of education using augmented reality,” she said. “As a geoscience education researcher, I’m really interested in further exploring the idea of how this can be used as a cognitive scaffold between two-dimensional (maps) and the real world.”

With some tweaks to its open-source software, the system might also help portray the distributions of atmospheric pressure that drive weather events and inform forecasts.

“The distribution of barometric pressure can be thought of as a topographic surface,” said Adam Houston, associate professor of Earth and atmospheric sciences. “There’s value in providing a connection to something that’s a little bit more tangible, something that you can literally manipulate with your hands. Ultimately, the reason we care about the heights of these pressure surfaces or the magnitude of pressure is because the gradients control the wind. This really bangs home that point.”

High-tech, low-maintenance

Considering its awe-inspiring outcomes, the sandbox consists of relatively few and easily obtainable components: a computer with a stellar video card, a projector, a Microsoft Kinect gaming sensor and, of course, 200 pounds of sand.

The Kinect transmits a net of near-infrared dots onto a surface – in this case, the sandbox – and measures how long they take to reflect and return to its sensor. Those measurements allow the system to calculate the distance of many individual points and ultimately define the three-dimensional contours of the sand. The readings are fed to a computer running open-source software that continuously assigns color values and simulates water dynamics based on the surface’s contours. Finally, the computer sends that information to the projector, which can update its overlays on a second-by-second basis.

Daren Blythe, the department’s instrumentation supervisor, assembled the system. Knowing the sand would occasionally require water, he built the sandbox from rot-resistant cedar boards and put the rig on a wheeled table.

That ease of movement should come in handy next year, when the department aims to use the sandbox in its introductory labs for the first time. Rebecca Dahlman, a senior computer science major, said she could see it enhancing the lessons on water tables that she and her classmates learned earlier this semester.

“It’s a more interactive way to learn, which is a lot more enjoyable than just looking at a topographic map,” Dahlman said before adding, “I want it.”

Frank said she thinks the high-tech sandbox might prove even better than its traditional counterpart at capturing the attention and imagination of the younger crowd, making it an ideal exhibit for outreach efforts that could inspire a future generation of geoscientists.

“What kids don’t like to play in sand, right? They’ll come away with some strong memories of using the sandbox,” she said.

“That might influence them later on and make them decide to go into science.”