Do people make a rational choice to be liberal or conservative? Do their mothers raise them that way? Is it a matter of genetics?

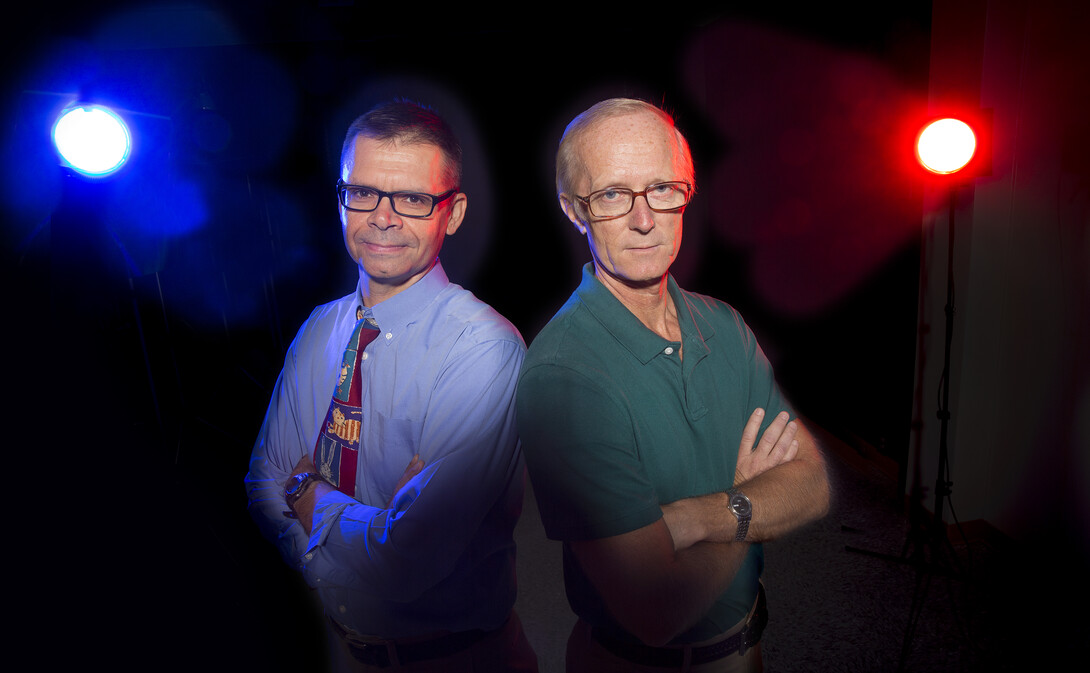

Two UNL political scientists and a colleague from Rice University say that neither conscious decision-making nor parental upbringing fully explain why some people lean left while others lean right.

A growing body of evidence shows that physiological responses and deep-seated psychology are at the core of political differences, the researchers say in the latest issue of the journal Behavioral and Brain Sciences.

“Politics might not be in our souls, but it probably is in our DNA,” says the article written by political scientists John Hibbing and Kevin Smith of UNL and John Alford of Rice University.

“These natural tendencies to perceive the physical world in different ways may in turn be responsible for striking moments of political and ideological conflict throughout history,” Alford said.

Using eye-tracking equipment and skin conductance detectors, the three researchers have observed that conservatives tend to have more intense reactions to negative stimuli, such as photos of people eating worms, burning houses or maggot-infested wounds.

Combining their own results with similar findings from other researchers around the world, the team proposes that this so-called “negativity bias” may be a common factor that helps define the difference between conservatives, with their emphasis on stability and order, and liberals, with their emphasis on progress and innovation.

“Across research methods, samples and countries, conservatives have been found to be quicker to focus on the negative, to spend longer looking at the negative, and to be more distracted by the negative,” the researchers wrote.

The researchers caution that they make no value judgments about this finding. In fact, some studies show that conservatives, despite their quickness to detect threats, are happier overall than liberals. And all people, whether liberal, conservative or somewhere in between, tend to be more alert to the negative than to the positive – for good evolutionary reasons. The harm caused by negative events, such as infection, injury and death, often outweighs the benefits brought by positive events.

“We see the ‘negativity bias’ as a common finding that emerges from a large body of empirical studies done not just by us, but by many other research teams around the world,” Smith explained. “We make the case in this article that negativity bias clearly and consistently separates liberals from conservatives.”

The most notable feature about the negativity bias is not that it exists, but that it varies so much from person to person, the researchers said.

“Conservatives are fond of saying ‘liberals just don’t get it,’ and liberals are convinced that conservatives magnify threats,” Hibbing said. “Systematic evidence suggests both are correct.”

Many scientists appear to agree with the findings by Hibbing, Smith and Alford. More than 50 scientists contributed 26 peer commentary articles discussing the Behavioral and Brain Sciences article.

Only three or four of the articles seriously disputed the negativity bias hypothesis. The remainder accepted the general concept, while suggesting modifications such as better defining and conceptualizing a negativity bias; more deeply exploring its nature and origins; and more clearly defining liberalism and conservatism across history and culture.

The article, “Differences in Negativity Bias Underlie Variations in Political Ideology,” was published in the June issue of Behavioral and Brain Sciences, a bimonthly publication of Cambridge University Press. It can be read at http://journals.cambridge.org/hibbing.