Planning to celebrate Halloween with a Freddy Krueger-Michael Myers-Jason movie marathon?

Sounds like fun, says University of Nebraska-Lincoln professor Brandon Bosch. As you do so, you may consider some of the messages in slasher films like “Nightmare on Elm Street,” “Halloween,” and “Friday the 13th.”

Bosch includes a lecture on “Gender in the Slasher Film Genre” in the Sociology of Mass Media class he has taught for the past three years. The American Sociological Association recently accepted his slasher movie lesson plan for its Teaching Resources and Innovations Library for Sociology, a peer-reviewed database of teaching materials for sociology instructors.

“It slices, it dices, it has entertained and scared audiences for decades – it’s the slasher film,” Bosch said. “Despite being dismissed by critics, the slasher film refuses to go away. Even if you don’t go to these movies, they are hard to escape, as every Halloween at least a few trick-or-treaters will dress up as a character from these movies.”

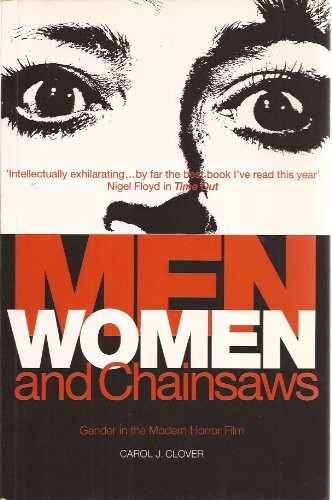

Much of Bosch’s information comes from “Men, Women and Chainsaws,” a book that examines gender roles in slasher movies.

“This has to be one of the most popular lectures I have during the semester,” Bosch said. “Most people have seen these movies, but even people that haven’t seen them know them.”

His class, Sociology 373, is aimed at students who are studying English, film studies, communication studies and journalism as well as sociology majors and minors. Slasher films are generally regarded as a subset of horror films. They feature a lone killer who stalks and kills a group of people one or two at a time until there’s one person left for a final showdown. Most of the deaths in a slasher movie are gruesome.

“The good and bad of slasher films is that they are incredibly formulaic,” Bosch said. “As a filmgoer, you don’t give them much respect because they have a carbon copy feel. But that makes them interesting to talk about because you see these patterns really easily.”

Some believe slasher films are misogynistic, he said, and some are concerned that they contain a volatile mix of sexual arousal and violence, which might be a dangerous crossing of developmental wires for young viewers. Highly feminine women – “bad girls” who indulge in sex, drugs and alcohol – get the ax, sometimes literally. Some scholars have timed the death scenes in slasher films and found they are longer and more gruesome for vampy female characters.

“With the men, it’s usually a clunk on the head and they drop like a sack of potatoes,” Bosch said.

Yet the protagonist often is a female character – “the Final Girl.” The character tends to be more boyish. She might have a more gender-neutral name like Stevie, from “The Fog,” or Erin in “You’re Next,” or even Laurie from “Halloween.” Her hair often is dark and short and she is a “good girl” who abstains from sex and drinking.

The killer isn’t usually a macho man. Michael Myers from “Halloween” and Jason from “Friday the 13th” are overgrown children. Chucky, from “Child’s Play,” is a doll. Leatherface from “Texas Chainsaw Massacre” dresses up as the mother near the end of that film.

Experts have conflicting views on why the genre developed and what, if anything, it says about society, Bosch said.

Some view the movies, which first appeared in the 1970s, as a conservative backlash to the loosening sexual mores and the feminism of that era. Others note that making a movie about scantily clad teens having sex and getting axed only became possible after the Motion Picture Production Code was loosened in the 1960s. Finally, the films are cheap, profitable and sequel-friendly, making them attractive to movie studios.

“It’s not necessarily that there’s this cultural clamoring for it, but from the executive side, this is cheap and enough people tune in to produce reliable returns,” he said.

Bosch says he is not a slasher-movie enthusiast – in fact, he’s too squeamish to get a flu shot. His lecture includes few violent movie clips and he warns his class in advance to look away if they are uncomfortable. He also gives students the option to skip the class and instead discuss the topic with him during office hours.

And, he added, his lecture has practical benefit for at least one student. During a Halloween movie marathon, she and her friends bet at the start of each movie on which character would survive. She won the pool.

“It’s a genre that people think is a stupid one, a guilty pleasure,” Bosch said. “Let’s just think and reflect on them. You can enjoy them for what they’re worth, but you can also think about them more sociologically and about how they’re representing gender.”