Imagine being locked inside your own body, isolated and struggling to meaningfully connect and communicate with those around you.

Now imagine trying to cope with such isolation as a child.

For children with severe speech and physical impairments (SSPI), the lack of a reliable communication method has devastating impacts on their quality of life, well-being, medical care and social interactions.

As advanced computer technology becomes more routine in daily life, researchers and engineers are exploring new ways to link it with the human brain. This involves creating a direct connection between the brain and control of an external device.

Brain-computer interface, or BCI, is an emerging field of study that aims to enhance quality of life for people with SSPI, offering increased communication and personal autonomy.

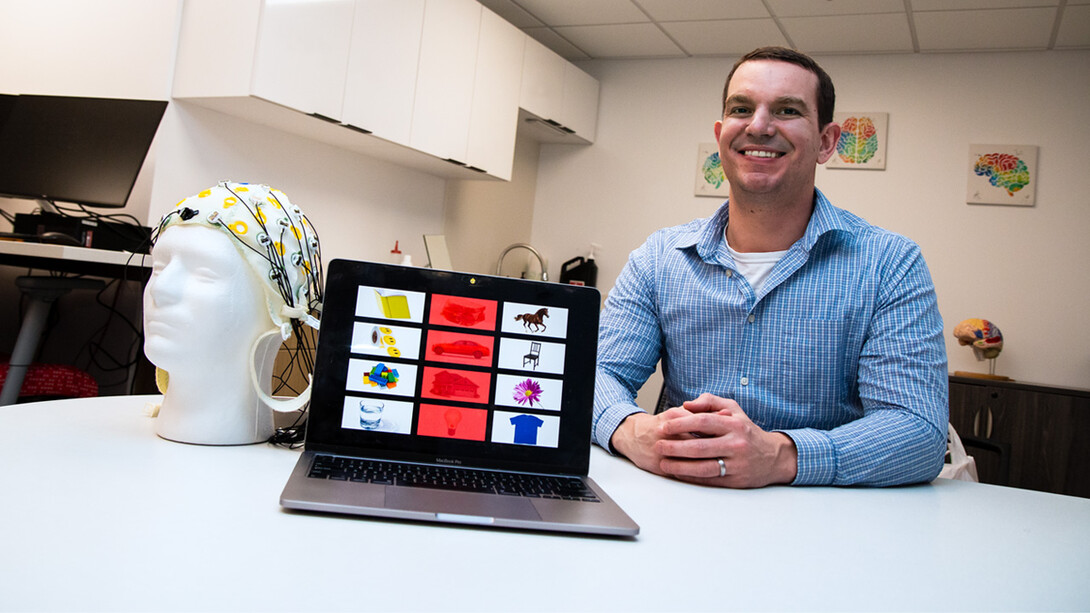

Kevin Pitt, assistant professor of special education and communication disorders, is leading a three-year project that uses this cutting-edge technology to facilitate communication for children with SSPI. The project holds great potential to support children who find spoken forms of communication unavailable or inefficient, and face challenges with computer access.

With funding from the National Institutes of Health, Pitt and his team are refining clinical evaluation tools and assessments to enable BCI technology, with the goal to make them more accessible to children. This includes evaluating preferences for engaging BCI design and integrating BCI with existing augmentative and alternative communications (AAC) displays used with pediatric patients, such as photographic picture boards.

Approximately 97 million individuals worldwide have disabilities that require AAC techniques for communication support. While adult-based BCI-AAC research has laid a crucial foundation, studies have primarily focused on providing literate adults access to spelling-based systems. Unfortunately, this has left children with minimal or emerging language and literacy skills marginalized and unable to communicate using BCI-AAC tools.

Using data from a 2022 pilot study of adults with SSPI — those living with spinal cord injuries, Parkinson’s disease, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS) and other severe physical impairments — Pitt tailored this project to focus on children.

“Children have been underserved in the BCI world, and only recently has research started ramping up to include them,” said Pitt, a research affiliate of the Nebraska Center for Research on Children, Youth, Families and Schools. “This project will help us better understand how to translate findings from adults to children, and how to implement BCI-AAC devices in the clinical setting.”

As with the pilot study, Pitt and his team are using the P300 BCI-AAC device — a communication tool that records brain activity through electrodes in a non-invasive EEG cap. The device reads electrical signals generated by the brain when the user identifies something as novel or different, enabling the user to select communication picture symbols via his or her brain activity.

Typically, to control the P300 BCI-AAC device, the user views letters or communication symbols on a display while they are highlighted for a short time. When the desired item is highlighted, the user’s brain emits an electrical spike detected by the BCI. This enables words and sentences to be communicated.

For this study, participants will view pictures instead of letters. Researchers will track users’ progress and learning with the P300 speller device, along with factors impacting their success and thoughts on how to make BCI-AAC designs fun and engaging.

Participants will include 40 typically developing children and 10 children with SSPI due to a diagnosis of cerebral palsy or muscular dystrophy, ages 8-12. Participants will try the BCI-AAC device in the Augmentative and Alternative Communication (AAC) Translation Lab in the Barkley Memorial Center on the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s East Campus.

Each child will attend three sessions for P300 training. For the first two sessions, Pitt and his team will track BCI-AAC performance as participants complete a requesting task — a simple choice of selecting an item — and a play task using tic-tac-toe, in which they select two symbols to take a turn on the board.

Researchers will collect data on users’ speed and accuracy, and will also measure attention, memory, motor skills and motivation to use the system. In the third session, participants will identify system design preferences — what the children liked and what could be changed.

“For example, our current BCI system highlights the pictures using red flashes,” Pitt said. “However, if users like motion instead of red flashes — a bouncing ball, or a dog that looks up or wags his tail, for example — we can design new interfaces based on what children want, leading to better engagement and motivation. We want to make it look cool and engaging, but also make these devices easy to learn.”

The goal, Pitt said, is to extend the reach and accessibility of BCI technology to patients of all ages — and to explore ways to integrate BCI-AAC with existing clinical practices in clinics, hospitals and rehabilitation centers.

“This will help expand the technology to a population that has been underserved,” he said. “I’ve always been motivated by helping kids participate, play and interact within their environment. We are one of the few labs in the world starting to think about how to promote clinically oriented, person-centered BCI-AAC access for children.”