Scientists have long recognized the key roles that zinc plays in human taste, and doctors have been prescribing supplements of the micronutrient for patients experiencing taste loss since the 1980s.

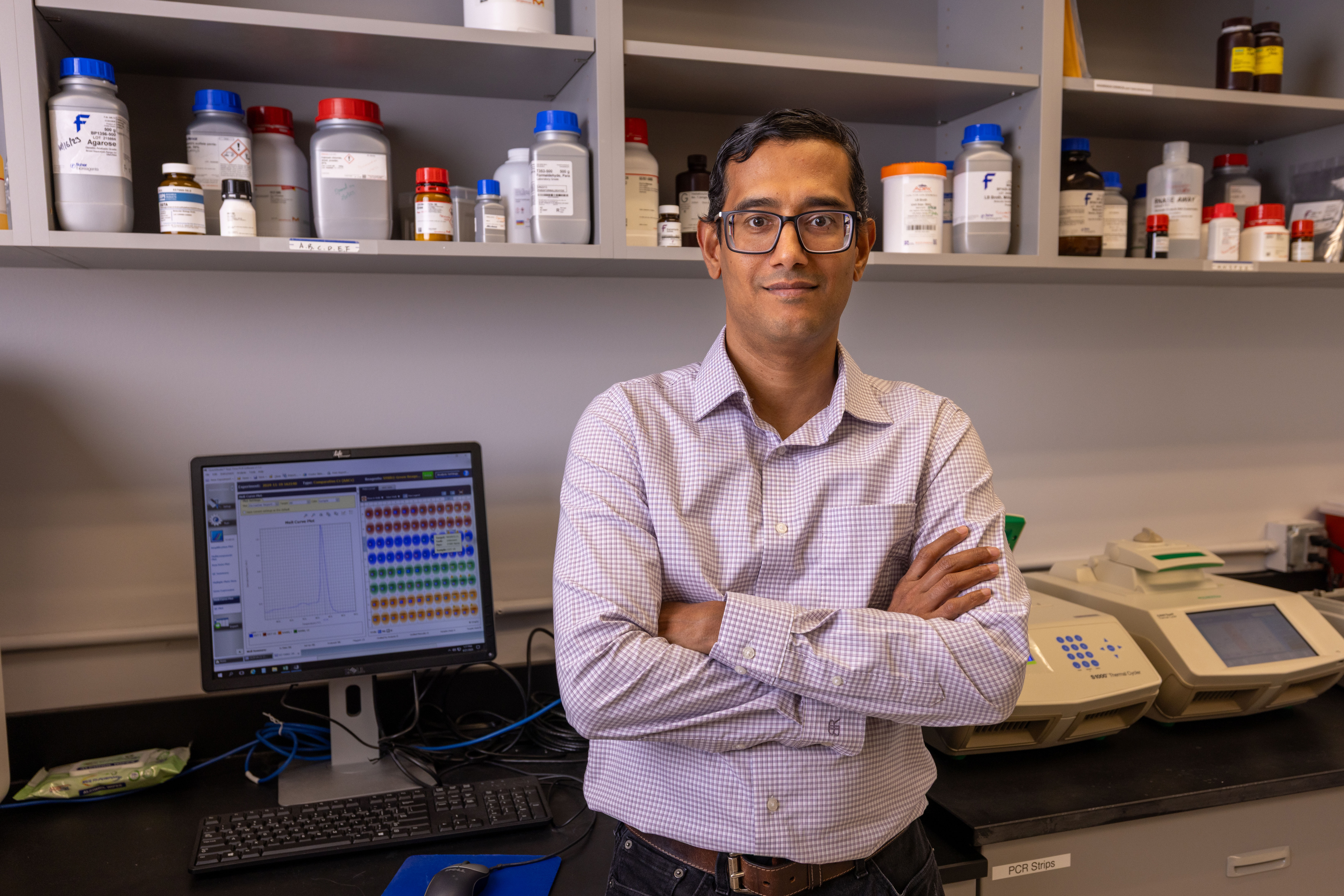

Despite the widespread practice, researchers still lack a clear picture of the molecular mechanisms by which zinc rehabilitates and governs the sensation of taste. University of Nebraska–Lincoln biochemist Sunil Sukumaran aims to change that. With a five-year, $1.5 million award from the National Science Foundation’s Faculty Early Career Development Program, he will use new tools in molecular genetics to pinpoint the biochemical pathways and molecular processes underlying zinc’s roles in taste cells. Better understanding these mechanisms will shed light on improved strategies for treating people with taste loss, which can result from injury, infection, chemotherapy and aging.

Sukumaran will also explore zinc’s ability to inhibit sweet taste. Research indicates that the mineral blunts perception of sweetness by about 75%, suggesting that zinc could play a role in curbing overconsumption of sugar, a leading cause of obesity and other metabolic diseases.

Zinc also plays a key role in immunity, growth and development, metabolism and cell regeneration in sensory tissues including taste, olfactory and intestinal epithelial cells. Because of these multifaceted roles, researchers have struggled to identify the mechanisms underlying zinc’s prominent role in taste cells.

“The mechanisms of how zinc governs taste are very complicated,” said Sukumaran, assistant professor of nutrition and health sciences. “When we look at a micronutrient like iron, for example, we know that its primary role is going to be in hemoglobin and a handful of others. Zinc is not like that: It’s so vital for thousands of enzymes and other proteins in the body, complicating efforts to pinpoint the pathways related to taste.”

To manage this complexity, Sukumaran first identified the most likely types of zinc-regulated cells and proteins in taste buds. Stem cells, with their ability to replicate and repair damaged tissue, were obvious candidate cells. Zinc transporters, the proteins that ferry zinc into and out of cells and help them maintain a stable level of the mineral, were the obvious protein candidates.

Using RNA sequencing techniques and histological approaches, Sukumaran identified about 20 zinc transporters expressed in taste stem cells. In sweet taste cells, he pinpointed one transporter expressed at a high level. This shortlist of zinc transporters is the jumping off point for his CAREER project, where he will use mouse models and taste organoids — artificially grown clusters of taste cells — to further delineate the role of each transporter and how they work in tandem.

Sukumaran said the project is possible because of new genomics tools that have unlocked the ability to study the cascading genetic effects of zinc deprivation and conduct “knockout” studies in taste organoids, which involve removing each transporter, one by one, to help clarify its function. These approaches include CRISPR screening and spatial and single RNA sequencing.

“We have new tools available now that didn’t exist five or 10 years ago,” Sukumaran said.

Beyond laying the groundwork for addressing taste loss and overconsumption of sugar, Sukumaran hopes his findings will illuminate zinc’s role in regenerating other types of cells, such as those lining the gut and those governing smell. He also expects his results may contribute to better understanding zinc deficiency, which affects roughly 2 billion people worldwide and is linked to adverse effects on fetal development and pregnancy outcomes.

Sukumaran also aims to help ameliorate the United States’ shortage of scientists through a partnership with Southeast Community College, a two-year institution in Lincoln. Like many community colleges, SCC is home to many nontraditional students who may lack knowledge about pathways to STEM careers. In addition, of the roughly 30% of students who transfer from two-year colleges to four-year institutions, only about 40% of them go on to earn a bachelor’s degree.

To create a smoother transition for transfer students and showcase STEM opportunities available at Nebraska, Sukumaran will offer 10 community college students a summer research internship in his laboratory, providing them with mentorship and academic support as they conduct research associated with the CAREER project.

He will also take his research to a population particularly susceptible to taste loss: older adults, many of whom experience diminished taste beginning in their 60s. Sukumaran will share his work with adult learners through the university’s Osher Lifelong Learning Institute, which offers educational opportunities to people over 50 years old. Boosting their knowledge about taste loss and potential treatments is important, he said, because it can impact these adults’ nutrition and mental well-being.

“What we now know is that when somebody loses their ability to smell or taste, the psychological effects are much harsher than when somebody loses their vision — even though vision is something we need every single waking moment,” he said. “That’s because the parts of the brain that process taste and smell are tightly linked to the regions that regulate emotion.”

Sukumaran will also showcase his work to the public, particularly families and children, at the university’s East Campus Discovery Days and Farmers Market.

The National Science Foundation’s CAREER award supports pre-tenure faculty who exemplify the role of teacher-scholars through outstanding research, excellent education and the integration of education and research.