Each fall, students enrolled in Brian Wardlow’s Introduction to Remote Sensing class make their way to the basement of Hardin Hall and into the Center for Advanced Land Management Information Technologies Spectral Lab at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln.

There, in a darkroom, they get to experiment with and demonstrate hyperspectral remote sensing — the method of scanning a material, such as a plant, to produce a unique spectral signature — beginning the process of what Wardlow calls “thinking spectrally.”

These exercises involving the scanning of plants, soil and water form an important foundation for students by teaching the science of remote sensing, and lead into more lab and class work using satellite or aircraft imagery to detect characteristics of land and water masses.

But this fall is different. The CALMIT Spectral Lab’s darkroom is small, and the 400-800 level remote sensing class is popular — enrolling 25 to 30 students each semester.

“Historically, we’ve always had challenges with fitting students into the space, and with social distancing, it became impossible,” said Wardlow, professor in the School of Natural Resources and director of CALMIT.

Needing a way to conduct those labs, Wardlow and his colleagues had to think outside the box — or rather, build one.

Wardlow consulted with Bryan Leavitt, a remote sensing technical staff member in CALMIT, to come up with a solution. With his nearly 30 years of experience performing hyperspectral remote sensing for the CALMIT lab, Leavitt came up with the CRISP, or CALMIT Remote Illuminated Scanning Platform.

After a few trips to hardware and craft stores, Leavitt and graduate assistant Ryan Moore built the mobile hyperspectral scanning system utilizing one-by-four boards, thick black felt, grommets and hooks. The large black box — or miniature darkroom — is able to be wheeled on a cart into any classroom.

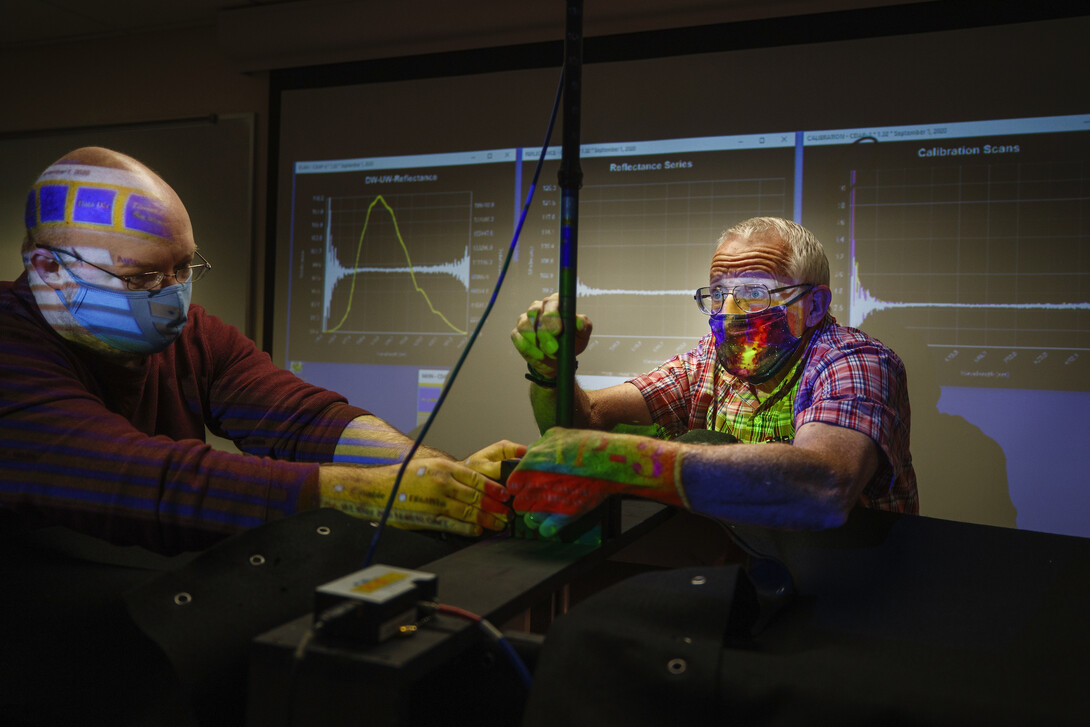

Leavitt designed the CRISP in such a way that the 250-watt lights illuminating the objects can hang at different heights and angles, depending on what is being scanned, and the system is lightweight enough that one person can handle setting it up, or putting it back onto the cart. The hyperspectral scanner is placed inside the CRISP and is wired to a computer and projector, which casts the spectral analysis on the classroom’s large projection screen.

The ability to remove the felt from the sides and top of the structure is also an important feature, as it allows for Moore to present the labs more visually for the students who are following along over Zoom, and for the students in the classroom.

“I think the instructors have done a great job making the course and labs engaging for students who are taking the class remotely,” said Levi McKercher, a master’s student in natural resource sciences.

Moore said using the CRISP has been beneficial to students in other ways, too.

“I think they can see more with the large projection screen as we’re doing the experiments and it allows for more interaction because in the darkroom lab, we were divided between two small rooms,” Moore said.

Without having CRISP this fall, Wardlow said the class would not have been as useful to the wide array of students who take it. The natural resources and geography cross-listed course typically enrolls students from a variety of majors because remote sensing has so many broad applications, from crop phenotyping to water quality to mapping UNESCO Heritage Sites.

“The course is designed to provide basic principles, concepts and foundational materials on what the field of remote sensing is, and its broad applicability,” Wardlow said. “These labs with the hyperspectral scanning provide the foundation to thinking spectrally, which allows for more meaningful interpretation of remotely sensed data from aircraft and satellites.

“When they actually start looking at imagery from anywhere in the world, they have those foundational concepts. They can think back and say, ‘Yeah, I remember that in the lab.’”

The pandemic has thrown a wrench in many plans, Wardlow said, but innovations like the CRISP that have come out of it are very wothtwhile. Aside from using the CRISP in the classroom lab setting, Wardlow sees new possibilities for its use in research and other educational training as well.

“I could see us using this in the university greenhouse, for example, or to demonstrate remote sensing capabilities to other parts of campus,” he said. “It’s completely mobile. The only requirement we have is needing a plug-in for the lights and our sensor.”

The shift to remote instruction in the spring also gave Wardlow the opportunity to redesign the class as potential online course offering in the future.

“The innovation here, in addition to the CRISP system, is that the entire course now — and it is one of the first in Nebraska and nationally — will be available for students to take remotely in the future,” Wardlow said. “This was one benefit from the pandemic, taking a class traditionally taught in-person, and now actually having it in a format where we could do distance learning very routinely, and in a meaningful way. It’s allowing us, I think, to start moving toward making the course more available to a broader audience.”