The 2017 total eclipse, which plunged the University of Nebraska-Lincoln into darkness at 1:02 p.m. Aug. 21, is history. Communicators at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln chronicled the eclipse at Nebraska, from start to finish.

9:16 a.m., green space north of Broyhill Fountain

It’s the first day of the fall 2017 semester, and City Campus is abuzz with that unmistakable start-of-the-school year energy and optimism. The hottest item around – other than full-color maps of the university for first-time students – are eclipse glasses.

Tyler Thomas, Lauren Becwar, Kellie Wesslund and other Nebraska staffers are spending the morning handing out the cardboard goggles – stamped with “8.21.17” and three full color-illustrations of totality on them – to students, faculty and staff. Since it is in the path of the once-in-a-lifetime event, the university secured thousands of pairs of the special protective eyewear to make sure the campus community experiences it safely.

“So when, again, does this happen?” says one student as she snags a pair. “I mean, when should we be using ‘em?”

“The whole event takes two hours, but the real action is between 12:45 and 1:15,” says Thomas.

“Guys, did you hear that?” the student says as she pivots to a small group of nearby classmates. “Get ready!”

10 a.m., steps of Selleck Hall

The arrival of a golf cart helps ignite eclipse fever at Nebraska.

As Thomas and Wesslund pull up on the north side of the Nebraska Union in the red and white golf cart, students start lining up to get free solar eclipse glasses.

“We knew there was going to be demand for the glasses, but nothing like this,” says Jon Gayer, coordinator of fraternity life for Greek Affairs. “The line at 9 stretched all the way across the plaza. We gave away thousands and thousands in the first half hour alone.”

Nebraska ordered 25,000 pairs of the specialized glasses to allow students, faculty and staff view the total solar eclipse. Another 1,000 pairs were donated to the university by NASA. Within the first hour of distribution, nearly half of the 26,000 glasses have been distributed by stations near the Nebraska Union alone.

Ella Xing, a sophomore actuarial science major from Shijiazhuang, China, is among students picking up glasses from Gayer on the front steps of Selleck Hall. As she steps away, Xing puts the glasses up to her eyes and peers skyward.

“This will be my first time seeing an eclipse,” Xing says. “There was one in China, but I couldn’t look at it because they ran out of glasses. I’m so excited to get to see it in Nebraska.”

11:15 a.m., Haymarket Park

Hoisted by her father to the eyepiece, Maeve Yellin is among the hundreds of baseball fans who look through a telescope at Haymarket Park as the solar eclipse is set to begin.

As Ian Yellin takes his turn, excitement bursts from his daughter.

“Dad! Look, water,” Maeve exclaims, pointing at a nearby water bottle.

Ah, toddlers.

The Yellin family is among thousands attending a daytime Saltdogs baseball game in conjunction with the eclipse. Nebraska’s Department of Physics and Astronomy partnered with the American Association baseball team on the day, organizing a science-focused exposition with information presented by students, faculty and staff at 15 booths. More than 3,000 tickets were sold to the game.

Faculty Brad Shadwick and Rebecca Harbison help the Yellins and other fans look through a Meade telescope that tracks the moon’s slow progress across the face of the sun.

“We’ve had a steady stream of visitors since we opened at 11,” Shadwick says. “It’s great to see so many people excited about the eclipse.”

The Yellins drove from Omaha to see the eclipse. Ian says having university experts on hand and offering extra information through the science fair are an added bonus.

“It’s really cool to see the university out here helping educate people about the eclipse,” he says. “This is a great event.”

The researchers also welcome the excitement level from the fans.

“I was going to make a big deal out of this eclipse no matter what. But it’s great to see everyone out here engaged and making a big deal out of it,” Harbison says. “I love that we’re able to help educate so many people and help them get a little glimpse of what the sun actually looks like.”

11:25 a.m., Greenspace north of Broyhill Fountain

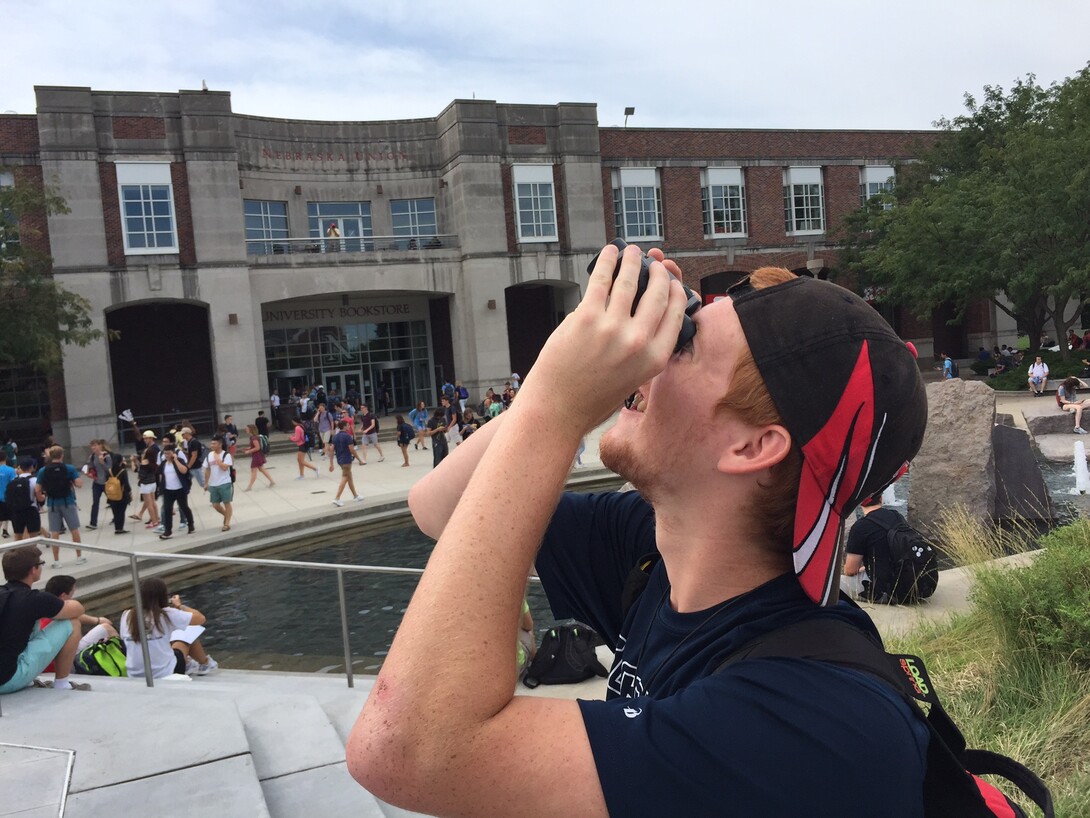

As the lawn behind him begins to fill in, and students whisk past staffers handing out the patented eclipse glasses, Will Seipel is hanging back and relaxed. In his right hand is a small pair of field glasses.

“You’ll hurt your retinas if you look through those,” a helpful staff member says.

“Nope,” Seipel replies, showing the shiny lenses with protective material on them. “They’re specially made for the eclipse.”

And they are – a glance through the field glasses show the sun as that dull orange ball, with the moon preparing to take a nibble out of it.

“My grandpa snagged a couple of these,” says Seipel, a sophomore civil engineering major from Omaha. “He was going to Beatrice to watch today, to get as much totality as possible, but he mentioned that he had an extra set. I was like, ‘Absolutely, I’m going to be on campus.’ ”

Seipel also holds onto a pair of free eclipse glasses from the university.

“You can never be too prepared,” he says, laughing.

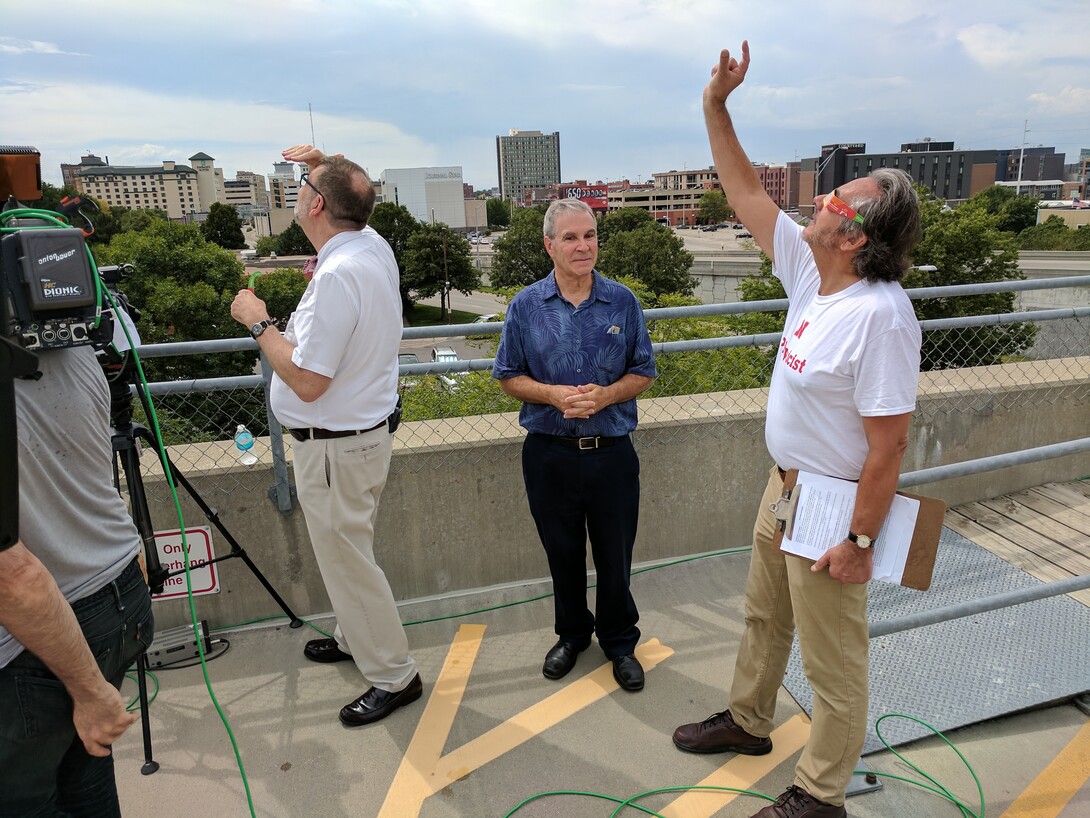

11:27 a.m., roof of parking garage just west of Memorial Stadium

Husker professors Dan Claes and Tim Gay, both of the Department of Physics and Astronomy, prepare to provide commentary for a recording of the eclipse being live-streamed on the university’s home page.

They’re joined by astronomer Richard Green, who has trekked to Lincoln from the University of Arizona to experience the total eclipse. Green, an alumnus of Omaha Central High School, attended his 50th class reunion last week and couldn’t pass up the fortuitous opportunity to witness the event firsthand.

“I have colleagues who go to every one,” Green says. “They mount these huge expeditions to exotic places. But this is my first one. It’s exciting.”

Hailing from Grinnell, Iowa, Pete Brownell and his family sit in a corner of the parking lot waiting for the show to begin. Brownell saw a partial eclipse “as a young boy” in the 1970s but hasn’t witnessed an eclipse since.

“We looked at the weather patterns, and this was the closest somewhat cloud-free site we could find,” Brownell says. “Plus, it’s a college town with good food. We haven’t been over here much, but it’s a nice place.”

As for how they ended up on the roof of the Stadium Drive Parking Garage?

“We figured anything with an observatory on top of it would have a good view of the sky.”

11:35 a.m., roof of parking garage just west of Memorial Stadium

“I’ve got visitors from England and San Francisco at my house, so I’m going eclipse-crazy,” says Gay, wearing a short-sleeve dress shirt and his signature bow tie.

Gay, Claes and Green receive their final instructions from David Fitzgibbon, director of video services for the university, shortly before the moon first begins to eclipse the sun at approximately 11:37 a.m. in Lincoln.

“All right,” Fitzgibbon says. “You guys ready to shoot this thing?”

“As ready as we’ll ever be,” Gay replies.

“Stand by,” Fitzgibbon says, shouldering a large video camera with his right hand while using his left to signal the start of the live-stream. 3, 2, 1…

11:39 a.m., East Campus, south of Chase Hall

Several dozen people gather on the north portion of the East Campus Mall, preparing to stare up in wonder at the heavens.

But first they are compelled to line up and answer an all-important question: “Chocolate or Scarlet and Cream?”

University employees Diane Wasser and Carol Wusk ask students, faculty and staff their flavor preferences before handing them small plastic containers of ice cream from a Dairy Store cart. They also direct every fourth or fifth person in line to where eclipse glasses are being distributed nearby.

Next to the cart is a table with a smorgasbord of colorful toppings – M&Ms, marshmallows, gummy bears, Skittles, Swedish Fish, various syrups – along with brown paper bags of popcorn.

Dairy Store employee and senior marketing major John Valencia, who helped with the setup, isn’t sure what to expect from the eclipse, but he knows one thing for certain: The treats will disappear quickly.

“Oh, they’re gonna fly,” he says confidently.

Noon, Greenspace north of Broyhill Fountain

It’s an hour until totality, the sky is beginning to get a strange gray, music is thumping on a campus PA system – and Paula Wurtz and Jessica Wiebe are hard at work with their cardboard boxes.

The two friends, who came to Lincoln from Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada, to watch the eclipse, are building eclipse boxes. They are punching pinholes into them to act as makeshift projectors on the ground, just in case the clouds that have swooped over the city don’t clear off in time – or are too thick.

“We’ll see it one way or another,” Wiebe, wearing a red Husker hat, says as she turned, solar glasses on, to check the moon’s progress. “We had a tent just in case we didn’t get a hotel room, but we were able to find one – so I’m feeling good about our chances here.”

What made them decide on Lincoln?

“We wanted to find the closest city with a university in it,” Wiebe says. “When we told people we were coming down, they were like, ‘Really? Why?’ We just said: ‘Why not?’ It’s such a rare event, how could we say we had the chance to drive 10 hours down to see it, but not do it?

“Plus, this is a really awesome scene,” she says, looking around.

12:02 p.m., East Campus Mall

“Uh-uh, that’s the icky part!”

Vanessa Wielenga implores her 2-year-old son, Felix, not to eat the top of the tomato as she carefully slices it for the bean burritos her family is having for lunch.

Wielenga, a dietitian who works for Nebraska Extension on East Campus, is sitting on a large brown blanket with her son and her husband, Joren Ries, a stay-at-home dad.

Wielenga has been camped out on the grass between the Home Economics Building and Entomology Hall since 11:30 and was later joined by her family, who arrived via bicycle. Father and son are wearing matching “Copy” and “Paste” T-shirts.

Wielenga says she and her husband didn’t get glasses for their toddler or explain in detail what the eclipse was because they thought he would be too young to fully appreciate it.

“We’re not making a huge effort to have him watch,” she says. “He doesn’t normally stare at the sun, so it shouldn’t be a big problem.”

Besides, Felix seems more interested in the plate of food in front of him than any celestial events about to occur.

12:33 p.m., Parking and Transit Services office

Thirty minutes until the eclipse and it’s business as usual at Nebraska’s Parking and Transit Services office on the first day of a new semester.

In a line of students streaming from the parking office, Raymi Marquardt, a junior psychology major, waited patiently for a friend who procrastinated picking up her campus parking permit.

“I’m organized and already have my permit,” Marquardt says. “Hopefully this line will move quickly and we’ll be able to get over to the green space by the (Nebraska) Union to see the eclipse.”

For both Marquardt and friend Jordan Mosel, a pre-elementary education major, this is a first eclipse experience.

“It’s been pretty well hyped and we thought it would be a cool thing to see — especially on the first day of the new semester,” Marquardt says. “I really wish it wasn’t so cloudy though. Maybe we’ll get lucky and get a good view.”

Dan Carpenter, director of parking and transit services, says eclipse activities made no impact on the number of students picking up or ordering permits on the first day of the fall semester.

“It’s a normal, first day of the semester in our office,” Carpenter says. “By the end of today, we will have helped between 800 and 1,000 students get their parking permits for the new academic year.”

12:37 p.m., south of Burnett Hall

Sheila and Bill Bonner of Omaha have brought their three children and a cousin to the university to meet up with their son, Bryce, a freshman.

The family claim a bench on the walkway near Burnett Hall. The area is shaded – in case the clouds dissipate – but the sun is still viewable, so it is a perfect place to set up a small picnic before the eclipse reaches totality.

“We brought the kids down because we thought it’s important to witness this,” Sheila Bonner says.

Sheila laments the clouds, but says they will make the most of the experience and then head back to Omaha.

“I think (Bryce is) ready to get rid of us,” Sheila says. “We’ve been here in Lincoln nearly every day since Thursday.”

12:45 p.m., Schorr Center (South Memorial Stadium)

Hopes for an eclipse viewing through the cloud cover starts to build among faculty, staff and students of Nebraska’s NIMBUS Lab.

“There are some clear skies over there, and with this wind, maybe we’ll get to see it,” says Adam Plowcha, a graduate research assistant.

To make sure team members are able to see the eclipse, NIMBUS Lab leaders ordered their own sets of solar glasses.

“Hopefully we’ll get to see some of the eclipse as it nears totality,” says Brittany Duncan, assistant professor of computer science and engineering. “Right now, that break in the clouds is looking pretty good.”

While some have gathered outside of the Schorr Center to watch, other members of the NIMBUS team are in west Lincoln, flying drones to collect data about atmospheric changes that occur during an eclipse. Leaders of that research project include Nebraska’s Adam Houston, associate professor of earth and atmospheric sciences, and Carrick Detweiler, co-director of NIMBUS and an associate professor of computer science and engineering.

12:51 p.m., west of Manter Hall

It’s not looking good as clouds obscure viewing of the eclipse when a cacophony of cheers and smattering of applause breaks out.

The clouds have parted. The sun — little more than a crescent visible — peaks from beyond the moon’s shadow.

“Finally, we’re able to see something,” says Peg Bergmeyer, a staff assistant in chemistry. “Hopefully, this break in the clouds will hold out.”

Bergmeyer is one of more than a dozen Nebraska staff employees from chemistry and biology departments to gather near the “Balanced/Unbalanced Wheels No. 2” sculpture in the green space west of Manter Hall.

12:52 p.m., observatory

Gay peers up to the sky, where clouds continue to obscure the sun. He puts on his eclipse glasses.

“It’s getting noticeably darker,” he says. “It’s looking pretty nice now, Richard. You should have a look.”

He notes that, despite the moon covering all but a fraction of the sun, it continues to provide a staggering amount of light. “It’s remarkable. I can look at that with my own eyes, briefly, but it’s remarkable to see that much light from such a little sliver (of the sun).”

12:55 p.m., Greenspace

It’s twilight during the noon hour – the Nebraska campus is tinged blue, making the students’ cell phones blaze brightly, almost as if they were checking texts during a movie.

Chancellor Ronnie Green, wearing a red-checkered Husker Oxford, makes his way through the crowd. He greets students, talks with them about their goals for the new school year, and – most importantly – gets his hands on a pair of solar glasses by a golf cart parked just north of the fountain.

Off come the chancellor’s prescription lenses, on go the solar glasses. Green folds his arms and goes quiet for 20 seconds.

“Now that is really, really cool,” he says. “Really cool.”

12:57 p.m., Plaza outside Hall Learning Commons

Sophomore Erin Hunter sits down on the concrete benches outside the Learning Commons. Her professor has dismissed class early so students can view the eclipse.

Hunter has her viewing glasses ready to go and is texting her mom back in Williamsburg, Virginia, who is seeing the eclipse there, albeit in “only” 85 percent totality.

“Ugh, she said it’s completely sunny there,” Hunter says.

As the atmosphere darkens, though, Hunter puts on her glasses and looks up.

“That’s so pretty! It’s a perfect crescent.”

The sudden darkness, coupled with the Nebraska humidity, reminds Hunter of summer thunderstorms.

“It feels like it’s going to start pouring on us any minute.”

She maneuvers her glasses over her mobile phone’s photo lens and takes a picture.

12:59 p.m., Greenspace

As the darkness starts to set in, Skylar Murphy turns on her phone’s speaker and plays Halloween music to set the tone of the event.

“I feel like the world is ending,” Murphy says.

1 p.m., Sheldon Sculpture Garden

Walker Pickering dances around between a pair of cameras — one a classic view camera using a pinhole for viewing the eclipse, the other a modern, DSLR for snapping images of students and others gathered in the Sheldon Sculpture Garden — excitedly talking about photography and the eclipse.

“This is so cool,” says Pickering, an assistant professor of art. “I can’t believe how intense the colors are even with the clouds.”

With the eclipse falling during class time, Pickering opted to take his introduction to photography students outside to experience the event first hand. In the time before the event, Pickering talked with students about how to safely photograph an eclipse and what they could expect during totality.

“This is an awesome way to start the first day of the semester,” says Daniel Allgood, a senior graphic design major. “And, it’s been interesting to learn more about what it’s going to be like during the eclipse.”

“It’s getting close now. I’m pretty excited about getting to see it.”

1:01 p.m., Greenspace north of Broyhill

As Lincoln steps to the precipice of totality, streetlights around Nebraska Union Plaza flick on and into service. The buzz in the crowd – hundreds strong by now – begins to grow.

A student who had been laying peacefully on Greenspace in a large inflatable beanbag, chilling in the sunshine for the past 45 minutes, gets to his feet. Thirty students on the south balcony of the Kauffman Center, who had been waving to their friends below, suddenly stop and look skyward.

A roar comes up from the crowd. Together, hundreds of Huskers look to the sky and cheer. Some punch the air. Others bounce on the balls of their feet. Chancellor Green, arms still folded, simply says: “Wow.”

And twice, the university’s famous call-and-response chant rolls through the crowd.

GO-O-O BI-I-I-G REDDDDD … GO! BIG! RED!

GO-O-O BI-I-I-G REDDDDD … GO! BIG! RED!

1:02 p.m., Stadium Drive Parking Garage

Dozens of onlookers have now gathered atop the parking garage, expectantly awaiting the moment when the moon completely blocks out the sun. As Mueller Tower strikes one o’clock in the distance, the sky gives new meaning to the phrase “shades of gray,” sliding across the gradient from ash to battleship to charcoal in just two minutes’ time.

“Photo cells have started to activate the street lights,” Green, the Arizona professor, notes, pointing toward the downtown skyline from his vantage point four stories above ground level.

Pete Brownell’s youngest son, Ruari, notices the subtle but abrupt drop in temperature.

“It’s getting colder,” he says. “That why I wore this long-sleeved shirt. Well, that, and it was my only clean one.”

Silence descends over the lot in the seconds preceding the totality. Hands reach for glasses, raising them to faces and dutifully placing them over eyes.

Though a veneer of clouds continues to mask the sun, it cannot mute the eclipse. Right on cue, the moon momentarily asserts dominion over the sun, blotting out all but the outer ring known as the corona. A cheer erupts from the onlookers, now bathed in a darkness normally reserved for dusk.

“There goes the sun!” Ruari exclaims. “Look at it!”

“That is awesome!” his mother agrees.

Another minute passes before an impossibly bright point of light appears at the right edge of the moon, easily piercing the clouds. A wave of astonished “Ohhhhh”s cascades across the lot.

“That’s the huge Diamond Ring,” Green says, referring to a signature phenomenon of the total eclipse.

The sky gradually lightens.

The moon has officially completed half its journey across the path of the sun.

1:05 p.m., Woods Hall, south steps

Michael Reinmiller, a digital media associate with the Hixson-Lied College of Fine and Performing Arts, stands outside Woods Hall with a big smile on his face.

“That was pretty cool,” Reinmiller says. “When it went dark, the colors were amazing and it got so quiet and calm. I loved it when the crickets started chirping. Amazing.”

Reinmiller has just watched the eclipse with his wife, Melanie Reinmiller. The couple’s wonder at the event continues as light returns.

“The birds are starting to tweet again, like they do in the morning,” Melanie Reinmiller says. “It went fast, but I’m glad we were able to experience it.”

As the nearby crowd in the Sheldon Sculpture Garden, Michael Reinmiller goes to collect the three Go Pro cameras he used to record the event.

“I can’t wait to watch it again,” Michael Reinmiller says.

The three videos are to be sent out via fine and performing arts’ digital arts Twitter account.

1:15 p.m., inside Hall Learning Commons

As the viewing groups begin to break up in the plazas and green spaces on campus, some students shuffle into the Learning Commons, sitting down with friends or finding a quiet space. Some of the more jovial groups join the line for coffee at Dunkin Donuts.

Senior Atiqah Ruslan takes the first seat nearest to the door, gets her phone out and starts texting.

“It’s only 2 a.m. there, but I want to send them pictures right away,” Ruslan says, and explains that she was sending photos to her family in Malaysia, where she grew up.

Ruslan also updates her social media.

“This is so cool,” she says. “I was surprised it didn’t get completely dark, but I could still see the ring.”

Ruslan says she viewed the eclipse with her friend. She’s grateful, she says, that she was able to experience it while a student at Nebraska, since Malaysia wasn’t in the eclipse’s path.

“The universities in Malaysia would not let students out early to experience something like this (anyway), so I’m glad I was here,” she says.

– Compiled by Troy Fedderson, Deann Gayman, Sean Hagewood, Hannah Pachunka, Scott Schrage and Steve Smith