Chad Brassil settles into a chair behind the 4-foot-by-3-foot pane of reflection-limiting conservation glass that he purchased from a local hardware store.

The neon orange dry-erase marker in his right hand pops against his all-black outfit and the black cloth draped behind him, accentuated by two lamps that usually reside next to the basement TV. He looks through the glass toward his iPhone, jerry-rigged in place with a selfie stick atop a tripod.

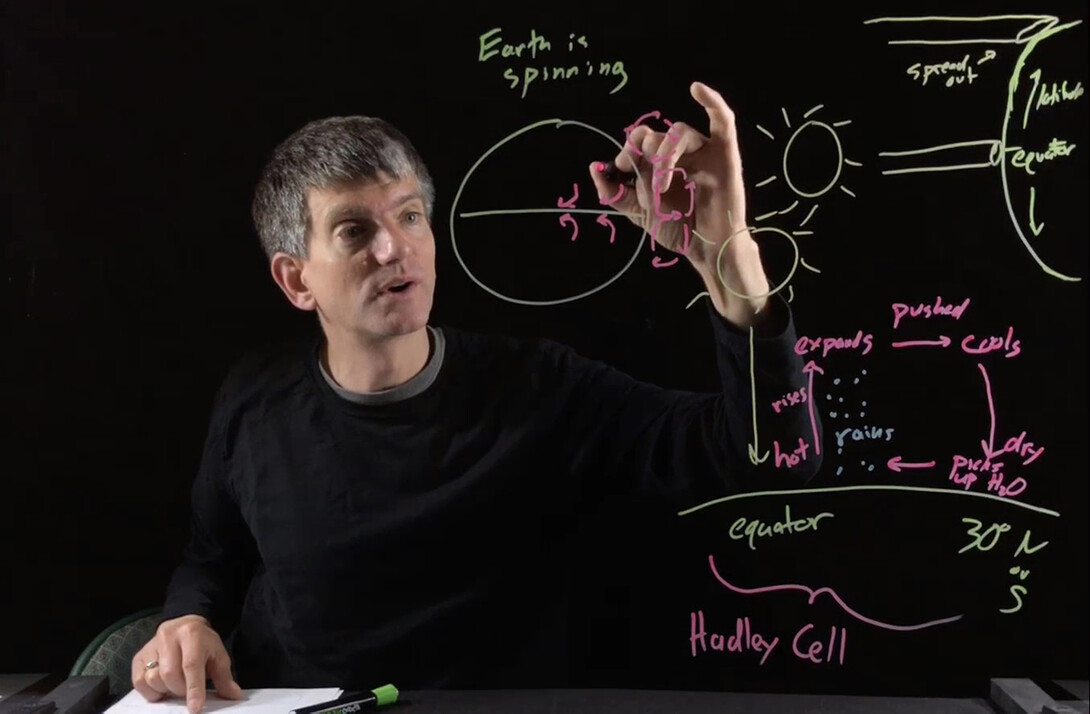

For the next 10 minutes or so, Brassil will record himself explaining a key concept from Life Sciences 121, a University of Nebraska–Lincoln course dedicated to a few fundamentals of biology: ecology, evolution, the tree of life, the physiology of plants and animals.

“Looney Tunes had it right,” said the associate professor of biological sciences. “They figured out that the standard Bugs Bunny cartoon should be about seven-and-a-half minutes. That’s about my target for a lecture tidbit.”

Brassil is no cartoonist, but soon he’s putting marker to glass, doodling images and jotting keywords as he relays the lesson to his iPhone and, starting in mid-July, his students. Under normal circumstances, Brassil would be preparing to teach the five-week summer course on campus. When he got word that the university would continue its remote instruction until the fall in an effort to curb the spread of the novel coronavirus, he set out to do what he could with the time and resources available to him.

“We all wanted to go into the summer semester pedagogically prepared, instead of this whiplash that we experienced in the spring,” he said. “There was plenty of time to think: How can I take this class and make it the best online class that it can be?”

Inspired by YouTube and the university’s Center for Transformative Teaching, Brassil decided to try his hand at a learning glass: essentially just a transparent, well-lit whiteboard that lends itself to making science more illustrative, comprehensible and personal. Some companies sell LED-embedded versions for thousands of dollars. Brassil built his own for about $100.

Since then, he’s been recording bite-sized, illustrated lessons and, when he’s done, digitally flipping the video so that the writing and imagery won’t appear backward to the viewer. By uploading the recordings to Canvas and making them available during the three-credit course, Brassil is hoping to give his students a convenient, memorable study reference.

“They might have an hour, hour-and-a-half of prerecorded videos to watch that day, but in these digestible 10-minute sections,” he said. “They can pause it, take some notes, go get a snack, do several practice questions and then go on to the next one.”

Though he’s never taught a fully online course, Brassil has spent the past several years recording and uploading lectures on reading assignments prior to class, along with summaries of key takeaways afterward. The decision has allowed him to spend more time in class asking questions and encouraging students to do the same, he said, helping him better gauge their understanding of the content and bring any especially fuzzy concepts into focus.

It also helped Brassil contend with a troubling sense of déjà vu that began arising after multiple semesters of teaching the same material.

“I started becoming what I call Encyclopedia Brassilica,” he said. “I’d be giving a lecture, and there’d be these kind of out-of-body moments where I’m going through the 50-minute lecture — the same lecture I’d given for four or five years in a row — and start to wonder, ‘Wait a minute. What year is this?’ You kind of get lost in time, and you’re not sure if it’s 2012, 2014, because you’re just repeating the exact same thing. You’re even repeating the same tics sometimes, the same little jokes. It felt like it should be more than me just repeating this thing.”

Another byproduct of the decision? A greater comfort with incorporating technology into the learning experience, which is proving useful now. But it wasn’t until a spring 2020 training session with the Center for Transformative Teaching that Brassil realized his recordings — especially amid a pandemic — were sometimes missing another form of comfort. It hit him as he watched Steven Cain, an instructional design specialist, open the training session not with slides but just himself, speaking directly to participants through the screen.

“I realized that I was connecting to him,” Brassil said. “I wanted this personal connection, especially when I was remote. It just felt warmer, like, ‘I want to learn what he has to teach me.’ And I realized that I probably need to give that to my students, as well, because they’re going to be in the same situation. They want to feel this connection.

“It’s kind of like connecting to a TV personality. If you’re watching Stephen Colbert, you feel like you know Stephen Colbert, even though he’s just looking out at the screen.”

Brassil initially intended to integrate that element into the summer course by adding a cropped recording of his face in a corner of the screen whenever he was running through content slides. Then he heard about the learning glass. He wasn’t surprised when he read a study suggesting that students seem to like the approach.

“I surmised that it was because of that experience I had — of the face-to-face almost intimacy that can happen through video,” he said, “combined with that nice, slow chalkboard pace of writing on the screen.”

As someone who’s spent much of his life learning complex processes and equations from biologists and mathematicians, then teaching students who aspire to become them, Brassil said he’s long appreciated handwritten instruction in the classroom. Because writing on a whiteboard involves turning away from students for significant stretches, though, he instead turned to a writable tablet that keeps the best aspects of the whiteboard and discards the rest.

“The students really liked that, because it harkened back to this era of the chalkboard where they can keep up with me,” he said. “Writing my notes slows me down to a pace at which the students can write at the same speed. It became a more personal interaction.”

Given that the learning glass shares those strengths, Brassil said he’s hopeful that his LIFE 121 students will find it worthwhile. Teaching the compressed course in an unfamiliar format — and without immediate, familiar feedback, from the nods that can signal understanding or sleepiness to the glances that can convey focus or confusion — is somewhat daunting, he said. But he’s drawing on that prior feedback to anticipate how students might respond, what they might engage with or dismiss.

And that sense of experimentation is helping him continue to close the book on Encyclopedia Brassilica, he said, while also keeping him busy at a time when feelings of productivity can be fleeting.

“It was a sense of, ‘I’m stuck at home. I want to do something to make this class better. What can I do?’” he said. “As I played with the learning glass, I thought, ‘This is really fun. Let’s keep going with this.’”

Click here to watch a demo of Brassil with the learning glass.