For Mark Griep and the UNL community, Rachel Lloyd was an enigma.

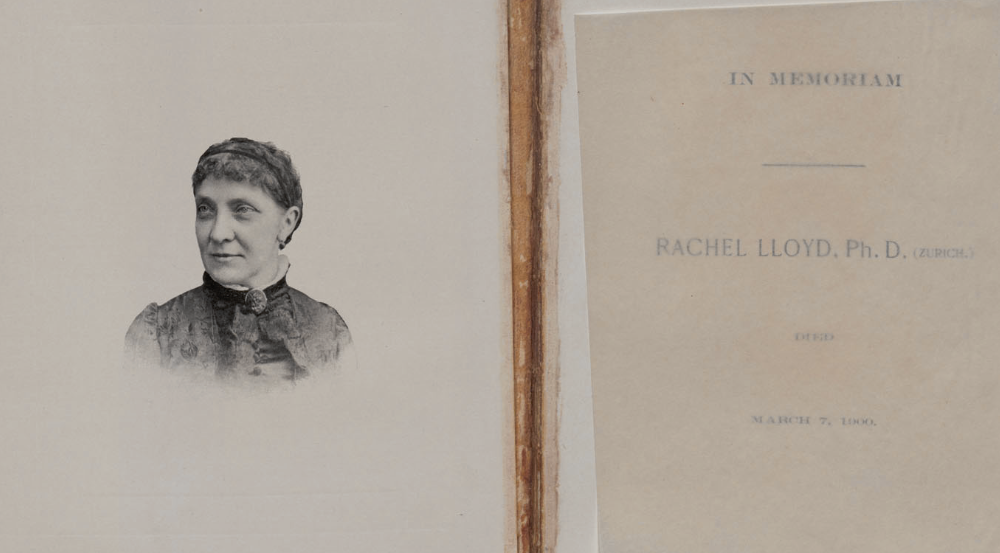

It was in a passing conversation in 1997 that Griep, associate professor of chemistry, learned that Lloyd had been possibly the first American woman to hold a doctorate in chemistry and that she had taught at Nebraska for seven years, even serving as acting chair of the department from 1892 to 1893. Griep, who enjoys researching family and community history, was intrigued with Lloyd’s story and wondered why there seemed to be no official photo held by the department or the university.

“I do family history and I love local history and relating my ancestors’ lives to their communities and what caused them to do what,” he said. “So I got interested in her story and the early story of our department. (Her story) is part of what makes Nebraska special, that there has always been this mentality of ‘anything is possible.’ ”

Griep pieced together information about Lloyd’s academic and family history, her groundbreaking research into Nebraska sugar beets and her years at the university, from 1887 to 1894. But many things still remained a mystery. He couldn’t find any information on why she pursued chemistry nor could he explain why she retired after only seven years.

He came across a 1901 article from the Philadelphia Times two years ago, advertising the publication of Lloyd’s biography by her brother-in-law, Clement. Griep searched the country for the manuscript, but came up empty-handed.

“I had been very frustrated because I wasn’t able to find a copy of this book,” he said.

He then sought the help of Keith Lindblom at the American Chemical Society.

“We checked everywhere she had worked or lived,” Griep said. “Nobody had it. I think one issue was that it was privately published. Since it was privately published, it wasn’t sent to the Library of Congress.”

Griep also didn’t have a good photo of Lloyd; the only photo he’d been able to find was in an old university yearbook. This bothered him – portraits of former chairs of the department are on display in Hamilton Hall. That mystery was solved by a 1916 article in the Red Cloud Chief, describing a time capsule included in the date stone of Avery Hall. The article explicitly said a photo of Lloyd had been included.

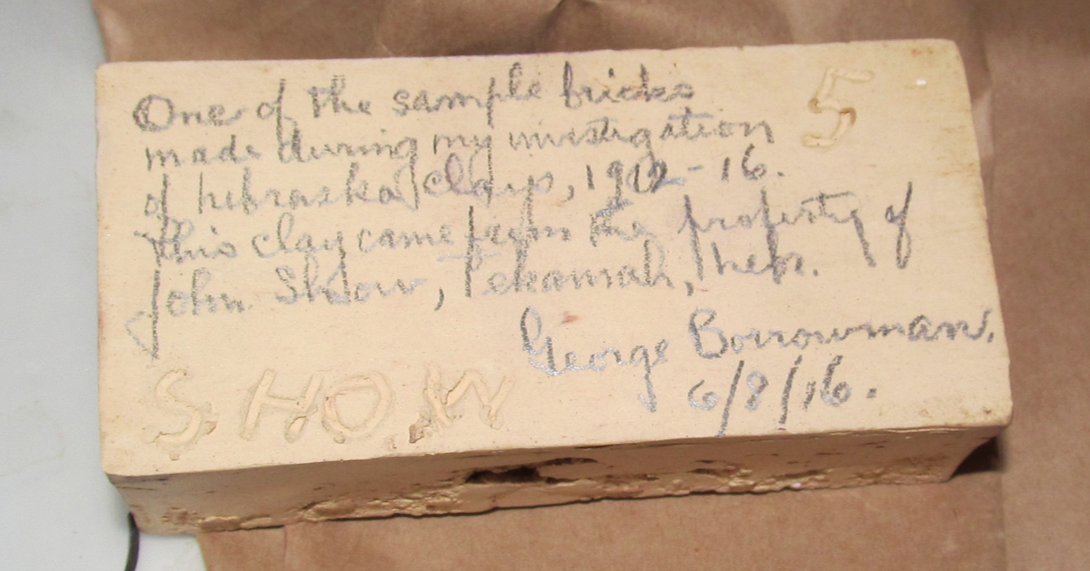

Griep gained permission to dig out the time capsule and did so in May. The contents were revealed this month – and much to Griep’s surprise, the manuscript he’d been searching for was also included. Despite nearly 100 years encased with chemicals, photos, old newspapers and other materials, the white book was in excellent shape.

Griep was ecstatic over the find and worked with staff from the UNL Libraries and the Center for Digital Research in the Humanities. Mary Ellen Ducey, an archivist, and Andy Jewell, associate professor of digital projects, University Libraries, took the manuscript and digitized it. It is now available to everyone at http://unlhistory.unl.edu/legacy/rachellloyd/rachellloyd.html.

“It was exciting to do because Mark was very enthusiastic and excited about the project and his enthusiasm was tangible,” Ducey said. “From our point of view, it was nice that we could work in collaboration with him on this. His purpose was to make it accessible to more people so they could see it and that’s what we do here as well.”

And Griep finally found the answers he’d been looking for – which only made Lloyd more impressive to him. Out of this respect he had for Lloyd, he worked to establish her as a National Historical Chemical Landmark by the American Chemical Society.

“She and her husband were religious and were focused on missions and what they could do for the greater good,” Griep said. “Her husband died after only five years of marriage and she eventually decided to teach.

“She became a science teacher at a girls’ school in Philadelphia. She immediately started focusing on chemistry, Clement Lloyd explained, because her husband had been a chemist and she believed she could best honor his memory by making it her mission to teach chemistry to girls. As a result, it was the first girls’ school to laboratory experiments in chemistry.”

Griep also made sure her efforts are recognized on campus and had her portrait hung among the chairs in Hamilton Hall. He hopes the photo will provoke students to learn more about her accomplishments and contributions to chemistry and Nebraska.

“She was a pioneer her whole life,” he said.