For most of American history, Black children rarely saw themselves in children’s literature, and even when they did, the depictions usually were condescending, paternalistic or outright racist.

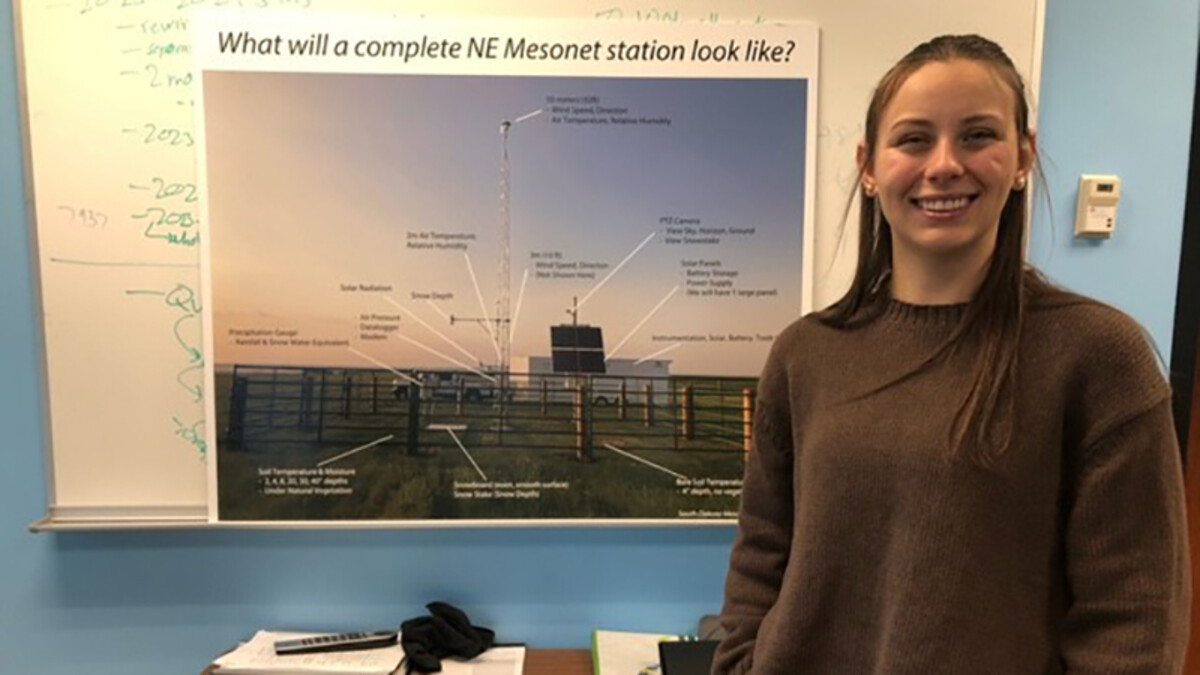

Amanda Gailey, associate professor of English at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, traces her interest in this subject to her time at Washington University in St. Louis, where a colleague approached her with the idea of creating a digital collection of children’s literature that would address how race was communicated to children.

“I found this very intriguing,” Gailey said.

Gailey has studied the period that began roughly during post-Reconstruction to World War II. Copyright issues complicated such collecting after that period.

Trends in children’s literature cannot be separated from the larger American history of those decades. In addition to spanning the nadir of race relations post-slavery, “this happened to coincide with the time that children’s literature as a genre exploded,” Gailey said. She cited the rise of free public education, more free time to read and advances in inexpensive publication of illustrated books.

“Children’s literature often tells us more about adults than it does kids,” she said. “It reflects what adults want children to think. You can look at the children’s literature and get some fascinating insights into the racial imagination of adults, and what they wanted to replicate in their kids.

“The most common message that kids were getting about race, overwhelmingly, is complete erasure of Black people.”

Children’s literature was almost exclusively white, both in who was writing it and who was represented in it. The rare children’s books that did address race tended to represent Blacks as servile or caricatures.

“Sometimes there would be paternalistic, condescending messages,” Gailey said.

A story might be about a white protagonist who was compassionate and charitable to a person of color. Jane Andrews’ 19th century “Seven Little Sisters Who Live on the Round Ball That Floats in the Air” was beloved at the time, among some even now, for its benevolent depiction of the peoples of the world as girls of different races. But, Gailey said, its depiction of the youngest, most helpless character as a Black baby is problematic.

Another book told the tale of a white boy and girl who went on various magical adventures. They were accompanied by a Black girl, shown throughout the adventures as their servant.

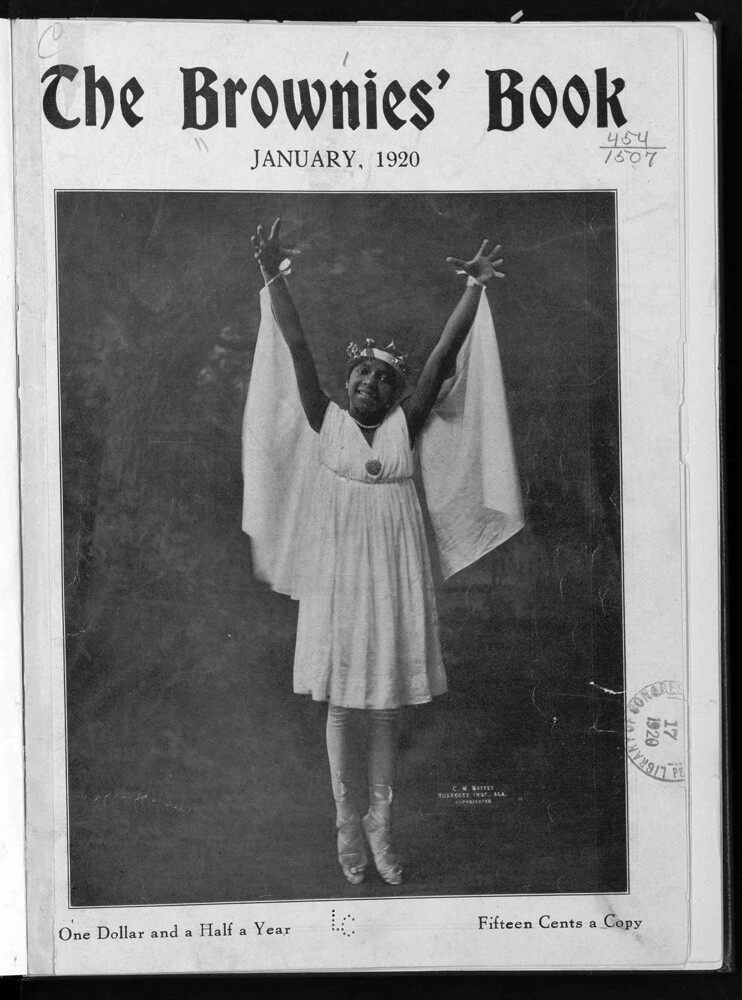

“The Brownies’ Book” showed children of color on its covers and told their stories inside. Fauset believed “there needed to be more material specifically written for Black kids,” Gailey said, especially since the news of the day was so grim for people of color.

The magazine lasted only a couple of years.

Much progress has been made in this century, and 2020’s reckoning on racial issues in America is driving a recognition that more needs to be made, Gailey said.

The University of Wisconsin’s Cooperative Children’s Book Center, or CCBC, has become the authoritative source nationally for tracking diversity in children’s and young adult literature. Since 1985, the center’s librarians have indexed every new book, providing data for a long-overdue re-evaluation of the publishing industry and promoting a more accurate reflection of a diverse world.

In 2000, the CCBC notes, less than 3% — 147 of more than 5,000 children’s books published — had a Black character. Only 151 books combined featured Asian, Latino/Latina or indigenous characters. Today, the CCBC says more than half of K–12 public school students are children of color, yet less than 15% of children’s books over the past two decades have contained multicultural characters or story lines. In 2018, roughly 10% of all children’s books featured Black characters, 7% featured Asian characters, 5% featured Latino/Latina characters and 1% featured indigenous characters.

Gailey said lack of representation is detrimental to white children, too.

“Their world is impoverished, too, when they’re led to believe their perspective and their identity” is the only one that counts.