A transformative technology known for separating biological components recently united students from disparate fields to honor its inventor with a permanent exhibit at the Nebraska Center for Virology.

In late-1940s New York, Myron Brakke was tasked with figuring out how to isolate a tumorous virus from the plant cells it was infecting. Brakke’s answer modernized the fields of virology and cellular biology, eventually making him the first Nebraskan inducted into the National Academy of Sciences.

That answer was the sucrose density gradient: test tube-housed layers of increasingly viscous sucrose, from soupy at the top to syrupy at the bottom, that purify biological samples for analysis after being spun in a centrifuge.

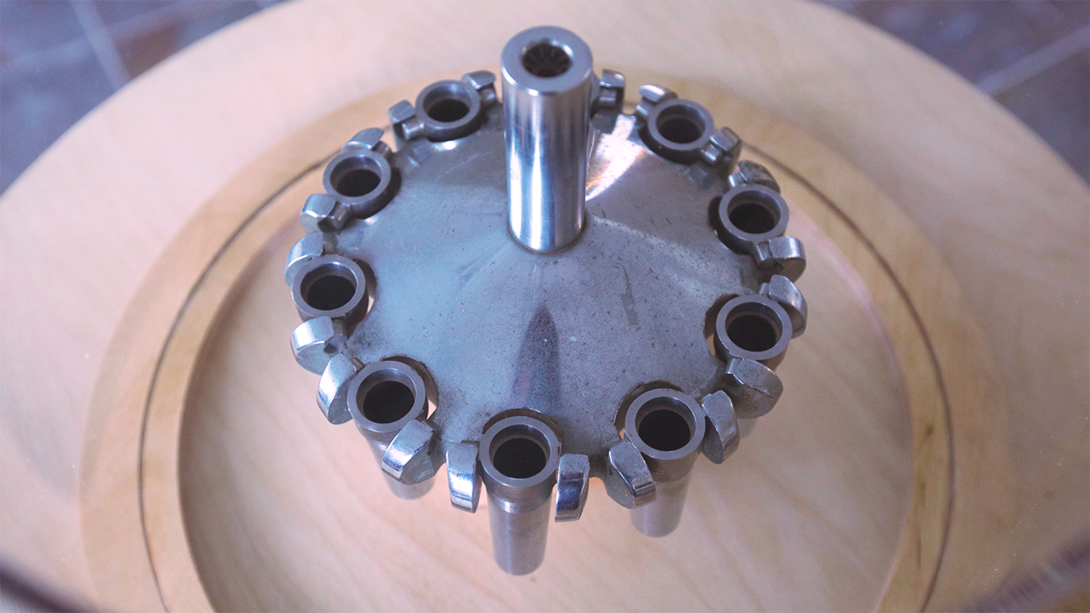

His invention’s mechanical signature, a specialized rotor at the heart of the centrifuge, would later appear in laboratories the world over. But the prototype moved with Brakke to the University of Nebraska–Lincoln in 1955, ultimately becoming part of a student-developed centrifuge exhibit and website unveiled in late April at the Morrison Life Sciences Research Center on East Campus.

‘There was always this idea that something should be done …’

When tubes of stratified sucrose are slotted into a centrifuge — a machine whose rotation can multiply normal gravitational forces up to 10,000 times — larger biological components manage to push through each sucrose layer and settle at the bottom. Smaller components such as viruses and proteins, meanwhile, get trapped in upper layers according to their size and shape. Among its many uses, the approach lets a researcher separate viruses from destroyed cells or isolate the specific organelles of cells themselves.

Yet the conventional fixed-angle rotors of Brakke’s era tended to force all components to the side of a tube that was typically slanted at 45 degrees, negating the benefits of the sucrose gradient. So Brakke also co-developed a swinging-bucket rotor that kept tubes perpendicular to the ground, allowing the gradient to work as intended.

“In the back of everyone’s mind, there was always this idea that something should be done with this rotor,” said David Dunigan, research professor of plant pathology and member of the Nebraska Center for Virology. “Because I tell people: This is not a swinging-bucket rotor. This is the swinging-bucket rotor. In his entire career, Myron Brakke had about 40 (scientific) publications. There are over 40,000 publications referencing this technology. There are very few technologies that have had that much impact.

“When I opened my first lab, the first piece of equipment I bought was a density gradient fractionator. Virologists, cell biologists, molecular biologists all use this technology. We use it daily.”

Going viral

The semester-long effort to create the Brakke tribute kicked off a new course named Exhibits that was housed at Nebraska Innovation Studio and conceived by Robb Nelson, doctoral student in history. Nelson, who hopes to pursue a career in the museum field, discovered that the university offered no formal program in the area. So he reached out to Judy Diamond, professor and curator at the University of Nebraska State Museum, for advice on formulating a course.

“This is only step one,” Nelson said. “We actually filed paperwork to create a graduate specialization in museum studies for the university, as well. This is the ground floor, but there’s more to come, hopefully.”

Alongside colleagues in advertising and graphic design, Diamond then organized a forum to solicit ideas for the course’s first project. Dunigan, who previously worked with Diamond on a virology-themed comic book called “World of Viruses,” pitched Brakke’s legacy as a candidate. The students liked what they heard and voted to move forward with the idea.

Aaron Sutherlen, assistant professor in the School of Art, Art History and Design, said his students were eager to enroll in the course and engage with the project.

“I’m a strong advocate for this idea of collaboration between different groups on campus,” Sutherlen said. “A lot of what we do in graphic design tends to be the decoration of things that might seem very superficial, and we get labeled as doing things that are sort of unimportant in the scope of something like this. I want (our students) to understand that they have the capacity to partner with people who are doing this very important work and use their skills as a visual communicator to help share that information with everybody.

As a master’s student in paleontology, Devra Hock is familiar with digging into the past, if usually on a much older scale. She took on the responsibility of reading Brakke’s research — including his seminal 1951 paper on the sucrose density gradient — and translating it into accessible descriptions that adorn the exhibit.

“I’m looking at going into museums for a career,” said Hock, who plans to pursue a doctorate with Diamond as a faculty adviser. “I can now say I’ve contributed to a full museum-quality installation.

“Going in, I didn’t know what it would be, exactly. But I left the first class thinking, ‘This is so cool.’ Getting to know the other faculty and students was a nice creative outlet. I grew up doing theater and dance, but getting to use that part of my brain a little more — and getting to know Judy — was invaluable for me.”

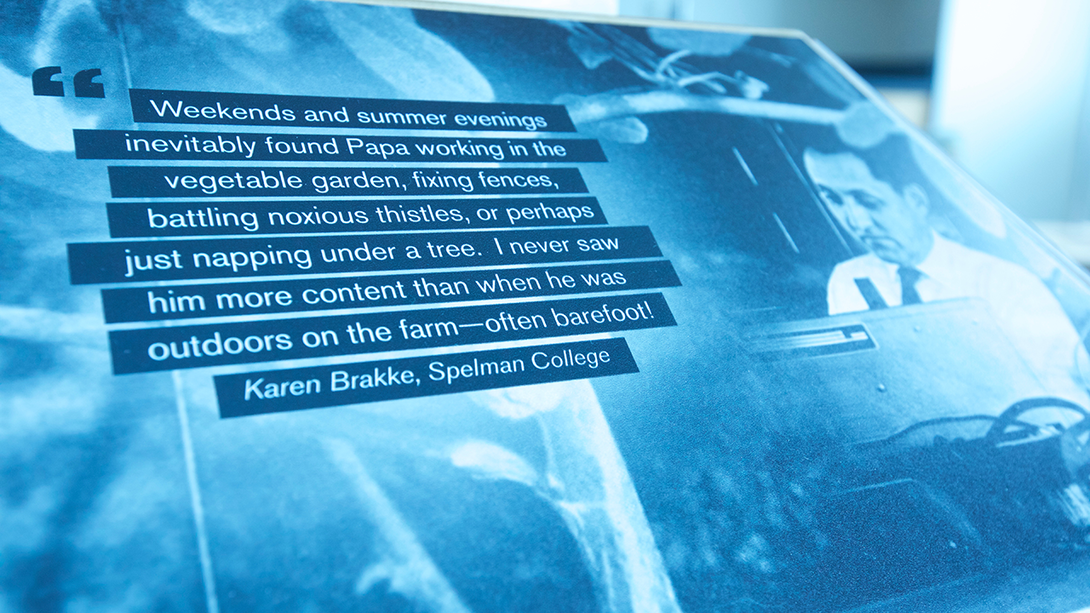

Hock also reached out to those who best knew Brakke, asking them to share thoughts and memories of their friend. She condensed several of the testimonials into snippets that likewise grace the exhibit.

“The purpose of the testimonials was to show who Myron was as opposed to us telling people,” she said.

The words used to describe Brakke at the exhibit’s unveiling echoed those of the testimonials: kind-hearted, humble, amazing.

James Van Etten, the William Allington Distinguished Professor of Plant Pathology, worked with Brakke for about 30 years. He told stories of how Brakke matter-of-factly dispensed profound insights that steered his colleagues’ research in fruitful and sometimes even groundbreaking directions, all without ever seeking credit for those contributions.

And when Brakke received word about the greatest recognition of his own career — membership in the National Academy of Sciences — Van Etten and other colleagues learned of it from a third party.

“I walked over and said, ‘Myron, what’s this stuff we’re hearing about you?’ He broke out in a big smile,” Van Etten said. “He had been told 24 hours before. He did tell me afterward that he had called his wife but hadn’t said anything to anybody else in the department. I have to contrast that with when I got elected: I didn’t go 10 feet before everybody in the building knew.

“One could meet Myron — and I know people who did — and never realize that he’d ever played any important role in virology or biology.”