A new digital humanities project from the University of Nebraska–Lincoln focuses on the non-European individuals who assisted the quests of famed Victorian explorers such as David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley.

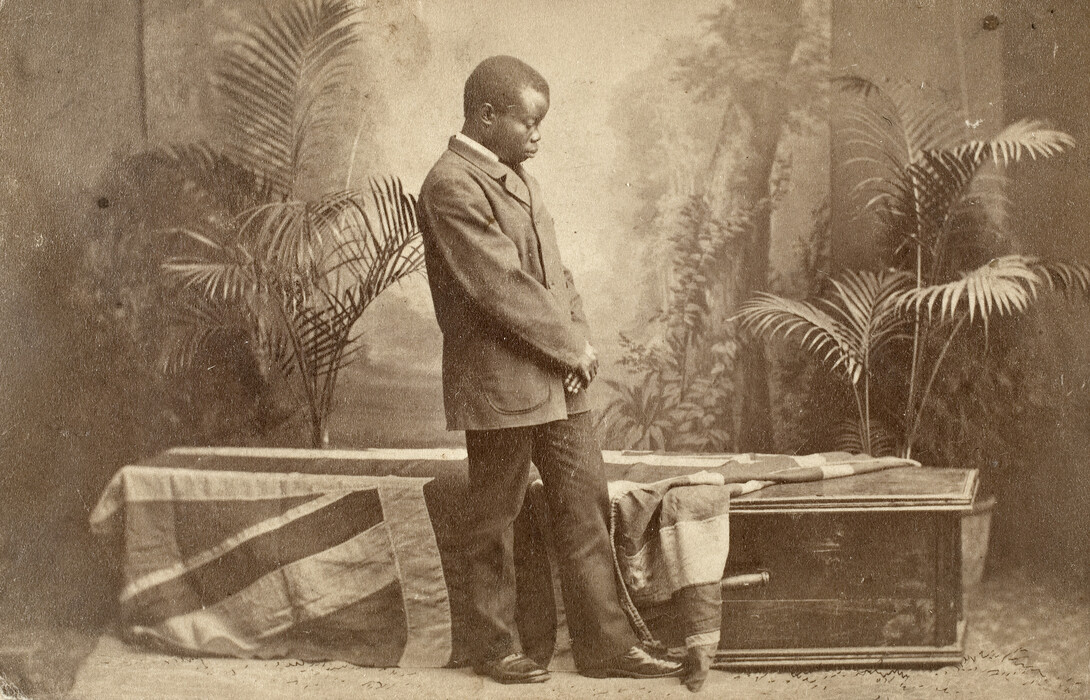

One More Voice gives access to long-neglected materials relating to people such as Livingstone’s assistant Jacob Wainwright. A member of the Yao ethnic group in east Africa, Wainwright gained public notice only when he sailed back to Great Britain with Livingstone’s casket in 1874, after Livingstone’s death in Central Africa in 1873.

The newly launched website includes critical essays, edited transcriptions of original materials and images of artifacts, bringing to life the variety of non-European voices that have long sat silent in the archives.

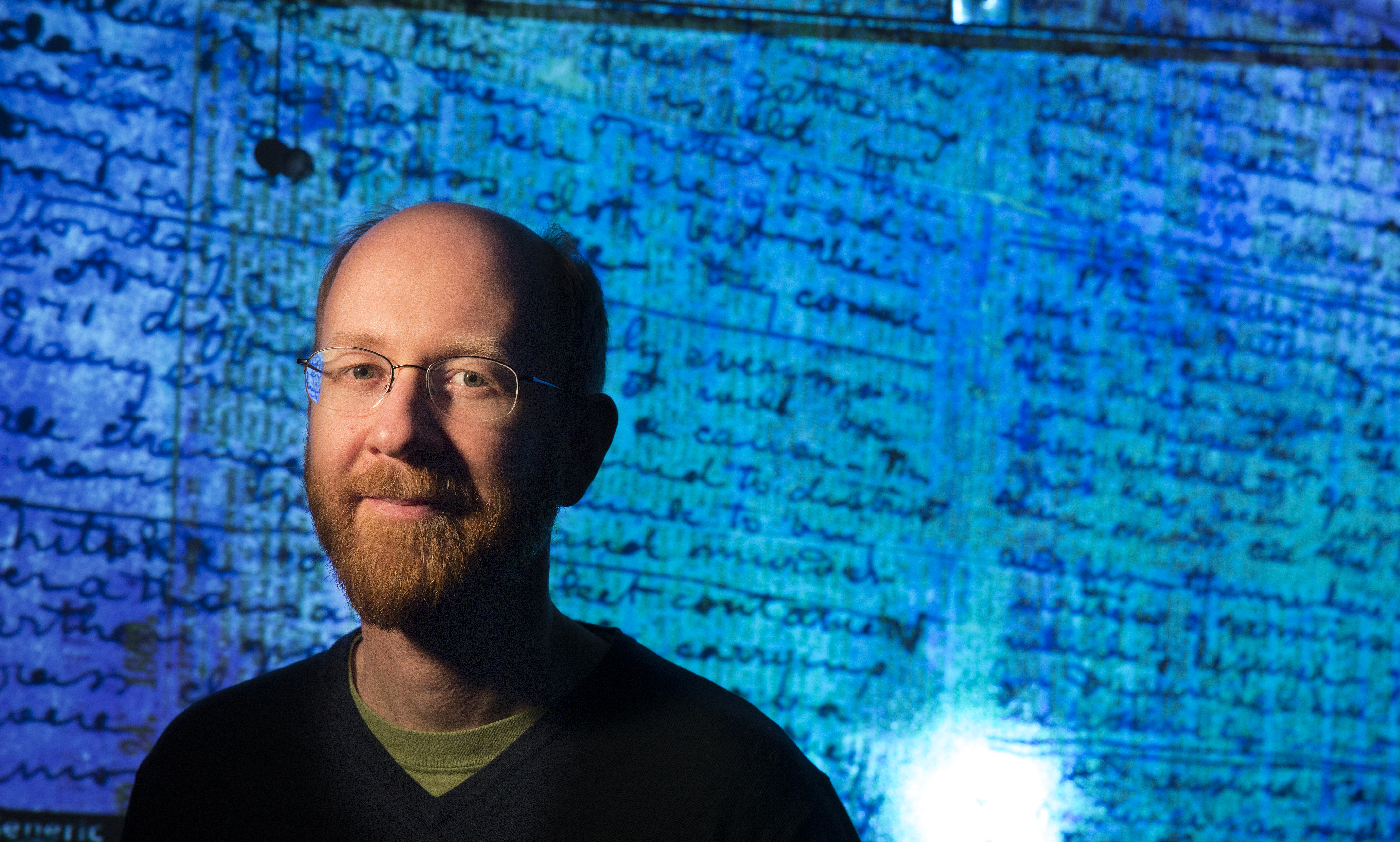

The project is led by Nebraska’s Adrian S. Wisnicki, a leading scholar of literature of the British Empire, and is being developed by a team of international scholars and archivists that includes Ng’ang’a Muchiri, an assistant professor of English at Nebraska who is serving as project adviser.

The goal of One More Voice, Wisnicki said, is to recover and disseminate the non-European contributions and stories previously excised from the story of European exploration. As the home page of One More Voice states, “The name reflects the fact that there is always one more voice to recover from the archives.”

“There is this idea of the heroic European explorer that plunges into the wild, has all these adventures and comes back and brings all this information,” Wisnicki, associate professor of English, said. “The reality is that history did not work that way at all.

“A lot of what was characterized as exploration by single European individuals was really the work of other people, gathering the ideas of other people, the data of other people,” he said.

Wisnicki learned of the vast number of such voices hidden in imperial and colonial archives during 10 years working on Livingstone Online, a digital museum and library that focuses on Livingstone’s legacy. The One More Voice project took shape over the past two years, although Wisnicki had been thinking about it and collecting materials much longer. He began work to launch the site with materials in hand after the global coronavirus pandemic forced him to cancel planned research trips in March to the National Library of Scotland and SOAS University of London.

One More Voice holds the largest digitized collection of the writings of Wainwright. It includes original pages of his diary, which made international headlines when the long-believed lost pages were found and published on Livingstone Online in 2019. One More Voice also offers four known photos of Wainwright and a previously unknown Wainwright text from the Victorian periodical press.

Although Wisnicki had to cancel his trip to the British archives, the work of recovering voices continues in earnest, thanks in part to ongoing collaboration with British archivists who have been supplying material to Wisnicki, and in part to Wisnicki’s work in searching through large-scale online text collections for long-forgotten pieces from the Victorian periodical press.

“What the project is trying to do is recover these materials, theorize about these materials, and so to see this aspect of history in a new and much more balanced way, one not just dominated by contemporanous 19th-century European perspectives,” Wisnicki said.