After reading 4,500 of the latest English-language novels, a University of Nebraska-Lincoln supercomputer named Tusker helped crack the bestseller code and explain why some books shine while others languish.

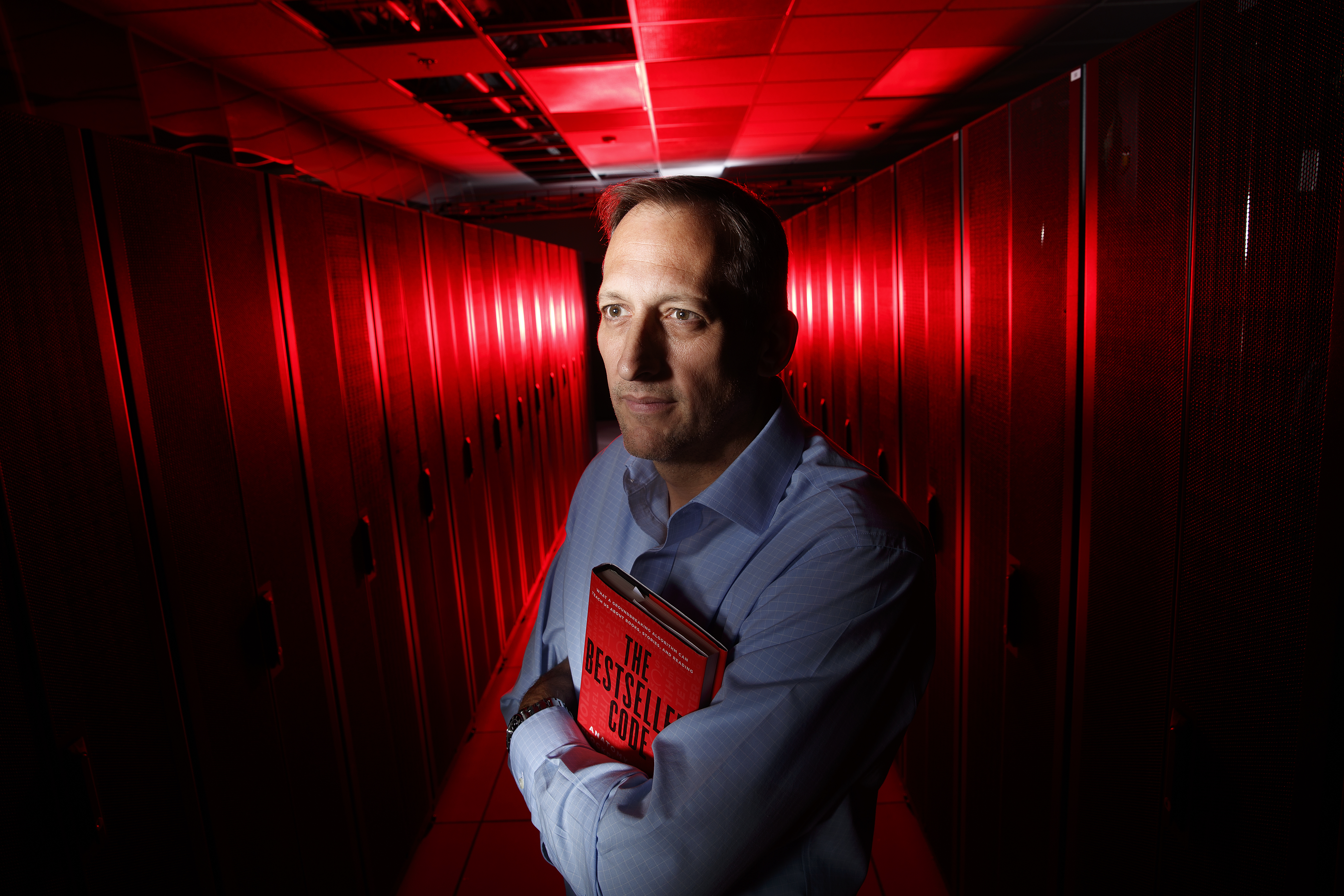

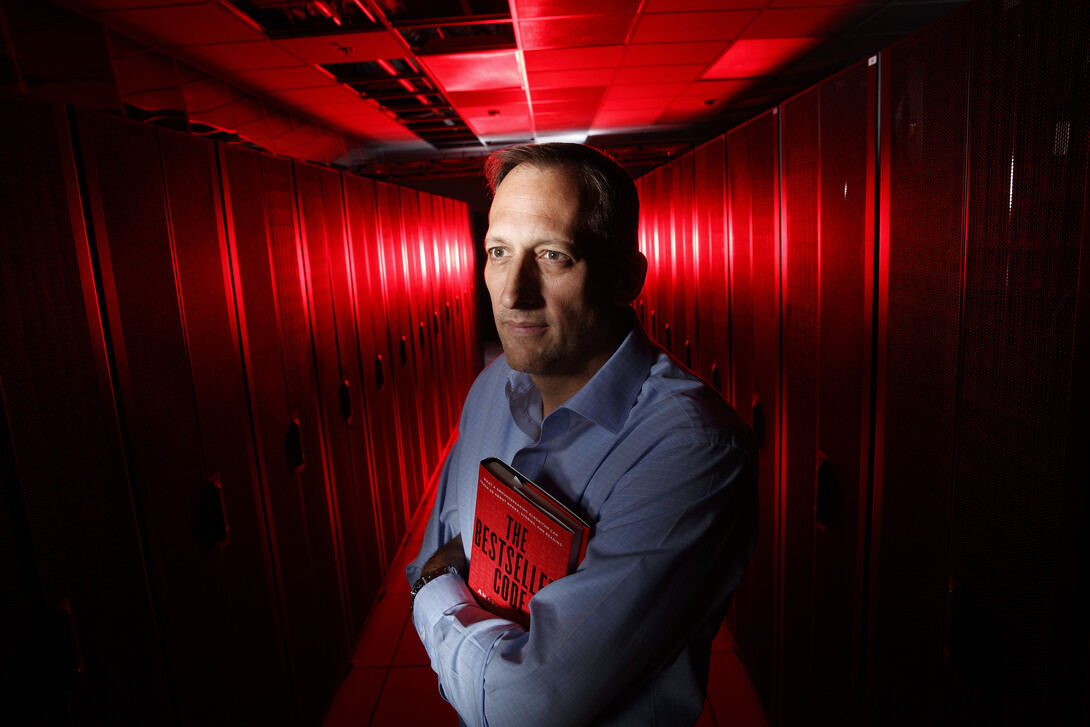

Matthew Jockers, an English professor and associate dean for research and global engagement in Nebraska’s College of Arts and Sciences, who uses computers to study literature, and his colleague, Jodie Archer, a former acquisitions editor for Penguin Books UK, enlisted Tusker in their quest to identify the secret to making the New York Times Bestseller List.

They found there is more to it than marketing, luck and a name like Stephen King. Their conclusions will be unveiled in their new book, “The Bestseller Code,” to be released Sept. 20 by St. Martin’s Press.

Tusker, a room-sized cluster computer based at the Peter Kiewit Institute in Omaha, is one of four supercomputer systems operated by the university’s Holland Computing Center. Red, the oldest and most powerful, is used by physicists working on the Compact Muon Solenoid project at the Large Hadron Collider in Switzerland.

Named for the mammoth-like creatures that once roamed the Great Plains, Tusker typically is used by biology researchers for gene mapping and genome sequencing, according to David Swanson, Holland Computing Center director, and Adam Caprez, a high-performance computing specialist.

For this project, Tusker’s reading list included some of the hottest novels published in the last three decades – titles such as “Fifty Shades of Grey,” “The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo,” “The DaVinci Code,” “Gone Girl” and “The Devil Wears Prada.” Perennial bestsellers Danielle Steel, John Grisham, James Patterson, Jonathan Franzen, Anne Tyler, Barbara Kingsolver, Lisa Scottoline and Jodi Piccoult were among the authors on the list.

Jockers worked with Emelie Harstad, a high-performance computing specialist at the Holland Center, to implement the algorithms that guided Tusker on the project.

“It was a particularly interesting project. It wasn’t a typical field like physics, computer science or even economics,” Harstad said. “It was kind of a unique use of our system.”

Tusker extracted approximately 28,000 features from each novel and then studied those data looking for patterns in word choice, sentence construction, topic, plot structure and pacing.

Using a form of artificial intelligence, it learned which features best differentiated a bestseller from a flop, identifying about 2,800 features that make the difference. In rigorous, class balanced cross validation experiments, Tusker was able to correctly identify the bestselling and the non-bestselling novels 80 percent of the time.

It took up to 15 hours of computer time for each novel studied, Jockers said. An ordinary computer would have had to run constantly for nearly eight years to complete the analysis. Tusker, with the equivalent capability of thousands of laptops, analyzed the novels in a matter of weeks.

Now in his fifth year at the university, Jockers specializes in text mining, a technique that uses high-powered computing to identify thematic and stylistic patterns among thousands of literary works. A co-founder of the Stanford University Literary Laboratory, Jockers first began working with Archer when she was his doctoral student at Stanford.

Archer’s publishing background piqued her interest in using text mining to identify the traits of bestsellers. Her doctoral dissertation, which Jockers supervised, formed the foundation for the joint project that resulted in “The Bestseller Code.”

“After her graduation, Jodie suggested we write a book together,” Jockers said. “Neither of us could have taken on this project solo.”

The pair continued their collaboration after Jockers moved to Nebraska. In fact, Jockers teaches a course on bestsellers at the university, with Archer serving as a guest lecturer.

Though Tusker is smart enough to recognize the hallmarks of a bestselling novel, the computer is not yet capable of writing one, Jockers added.

Writing a successful novel still requires creative and critical thinking, Jockers said. Even though computers can be programmed to write, such efforts often pull strongly from previously published works, shared online texts and input from programmers.

“We would rather just sit down together with pen and paper and use the findings of our research to attempt to write a novel ourselves,” Jockers said.