The dishes on the table draw on Sandra Williams’ Peruvian heritage — Lomo saltado, a stir fry that reflects the culinary influence of Chinese/Asian histories in Peru, and papas huancaina, a rustic potato dish from the Andean highlands.

Sitting under the table are Gladys and Arthur, Williams’ rescue dogs and prowling around the dining room and kitchen is Armando, the cat she adopted after fostering him for a few weeks.

The books on the other end table are evidence of research for a book about street art that has taken Williams to Mexico City and Alliance, Nebraska.

And the ceramics on the wall shelves on the wall link Williams to art school in her hometown of Cleveland, Lincoln, and, by extension, to the Amazon rainforest and Key West, Florida.

Those places and the pets connect the diverse practice of the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s associate professor of art that combines public art and murals, her distinctive bright colored resin pieces and delicate paper cuts, and her interdisciplinary educational endeavors.

In Cleveland, where Williams’ Peruvian mother, a nurse, met her policeman father in the hospital where she worked, Sandra found her twin passions when she was a little girl — art and animals.

“I’ve always loved animals,” she said as Arthur jumped onto her lap, begging for a treat. “I think my other choice in life was to be a vet. But I remember shadowing a vet when I was in high school, and thinking, ‘This is horrible. I really can’t do this.’ You think you’re going to be helping animals, but there’s so much other stuff that goes with that job. So, I ended up going to art school.”

That school was the Cleveland Institute of Art, where Williams, who studied ceramics, developed the aesthetic that has continued to inform her work for two decades.

“If you look at (UNL ceramics professor) Eddie Dominguez’s work, if you look at a lot of people who came out of that program, there’s this aesthetic, they call it the Cleveland cloisonné because there tends to be bright color, black line,” Williams said, pointing to a pot on the shelf. “That’s very present in Peruvian work, too. That pot there is narrative, it’s carved, the black line and bright color. That’s what I discovered there.”

That aesthetic is clearly seen in the large, polyurethane pieces that were Williams’ primary medium of the 2000s, brightly colored, thick works most often depicting a person with plenty going on around them, or, atop them as butterflies, communion wafers, feathers and dirt made their way into the resin.

In 2014, however, Williams’ medium and, to some measure, aesthetic changed, moving from one of the heaviest artworks to one of the lightest.

That happened when she embarked on a 2014 residency at the Madre de Dios Biological Research Station, located deep in the Amazon rainforest, where she intended to look at animals, especially species facing extinction.

Because she had to pack all her art materials in and out of the rainforest and couldn’t use anything with toxicity, she turned to working with cut paper.

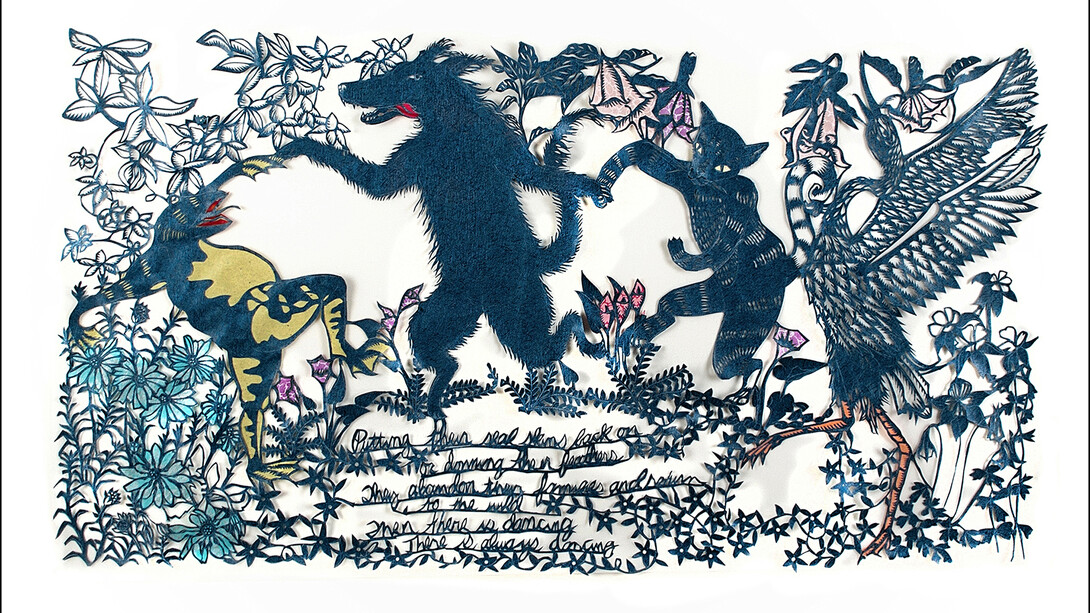

The cut paper pieces that have followed from the Amazon trip are exquisite and delicate, narrative through images and text, sometimes colorful, sometimes in black and, largely, address the collision of humans and animals in the natural world.

But, of late, they veered into “Eat a Peach,” an exhibition about love held at The Studios of Key West, the gallery and community where Williams’ work has been best received.

Williams, who came to UNL to teach visual literacy in 1999, undoubtedly has passed some of the CIA aesthetic on to her students. But more importantly, she’s passed another primary element in her oeuvre—public art and working collaboratively in the community, work that can be found in her organization of Day of the Dead celebrations and, more pertinently, in street art and murals.

She’s passed that interest on by developing one of few street art classes offered in any university, a course informed by her trips to Mexico City and Puebla, Mexico, where she found murals that incorporated the lives of indigenous people, something she didn’t experience in school.

“When I was in art school, I never saw myself reflected in academic culture,” she said. “I think there was one day in my sophomore year, when our instructor showed us a video on Frida Kahlo. That was it.”

Murals, in contrast, include all races and ethnicities, and often deal with social justice and other contemporary issues, which is of great interest to UNL’s art students.

“This is a pretty diverse school, and I think that street art really captures that audience,” Williams said. “I think those people equally love our regular art history classes. But this class talks about George Floyd, and it talks about COVID, and it talks about political uprising and it talks about feminism. So there are a number of students who may find it more germane to the way they live life.”

And, Williams pointed out, street art, which includes graffiti, is great fun for the viewer and the artists.

“There’s a certain playfulness, as well as the subversion that I like,” Williams said. “This sounds terrible, but I’m going to say it anyway. I think subversion and resistance is really essential to young people’s education. When I’ve had them go out and do stencils with spray paint, and these are college kids, they have so much fun. Even if we have permission, it feels a little bit naughty. They like it.”

Street art is also what brought Williams and a pair of students to Alliance to create a mural, which, in turn, led her to become part of RIZE with Insects, a UNL Grant Challenge project in which she is collaborating with experts in child, youth and family studies, entomology, science communication and psychology to create a camp for first and second graders to study insects and planetary health.

“Because I’ve always been interested in animals but didn’t pursue that other interest of mine, it didn’t mean that I would have to cut it out of my life,” said Williams, who started working with scientists during her Amazon residency. “Transdisciplinary work is something that I’ve wanted to do for like 17 years. But until there was a format for that, it was really hard to find a team or a partner or someone who would make time for it.”

As for her own work, Williams foresees another change in medium and scale in the near future.

“For the past nine or 10 years, I’ve been pretty successful showing my paper cut work,” she said. “Now, I don’t want to talk about it too much, but I want to turn it into public art. Like, what do those paper cuts look like when they’re cut out of steel, and they’re 12 feet tall, and the monkeys are on rods, and they can spin in the wind?”

She’ll be doing that work along with teaching in Lincoln, where she intends to stay until retirement. Then, she’ll likely find a place to get away from the winter ice, snow and cold.

“I’m seriously considering retiring to Mexico City,’ she said. “Mexico City is lit. And your tears don’t freeze to your face there.”