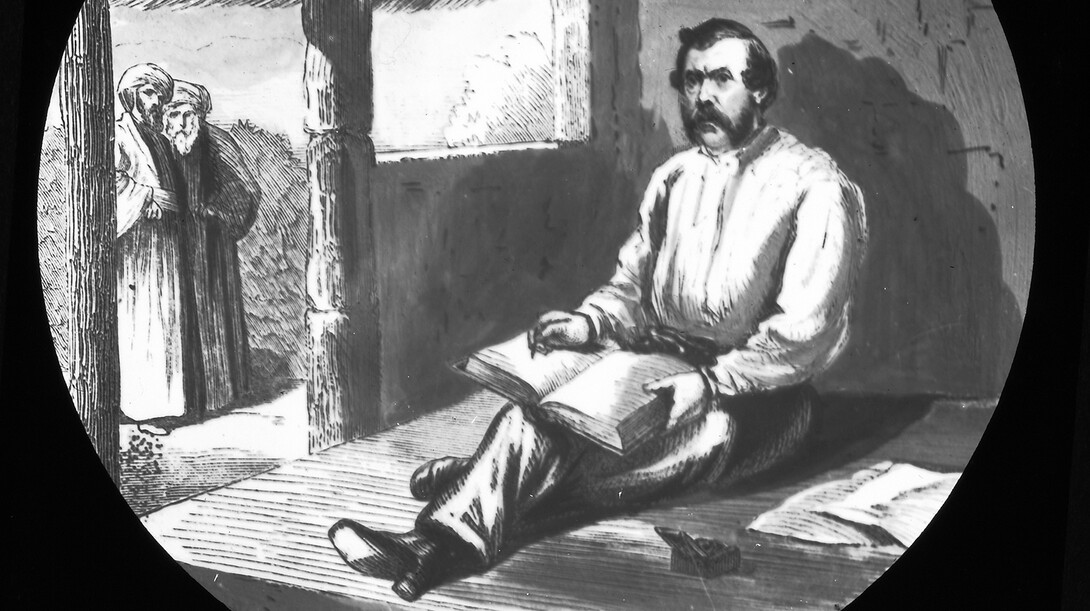

Long hidden away in archives and repositories, renowned British explorer David Livingstone’s testimony of the East African slave trade and its horrors only existed on the pages of centuries-old diaries and other manuscripts.

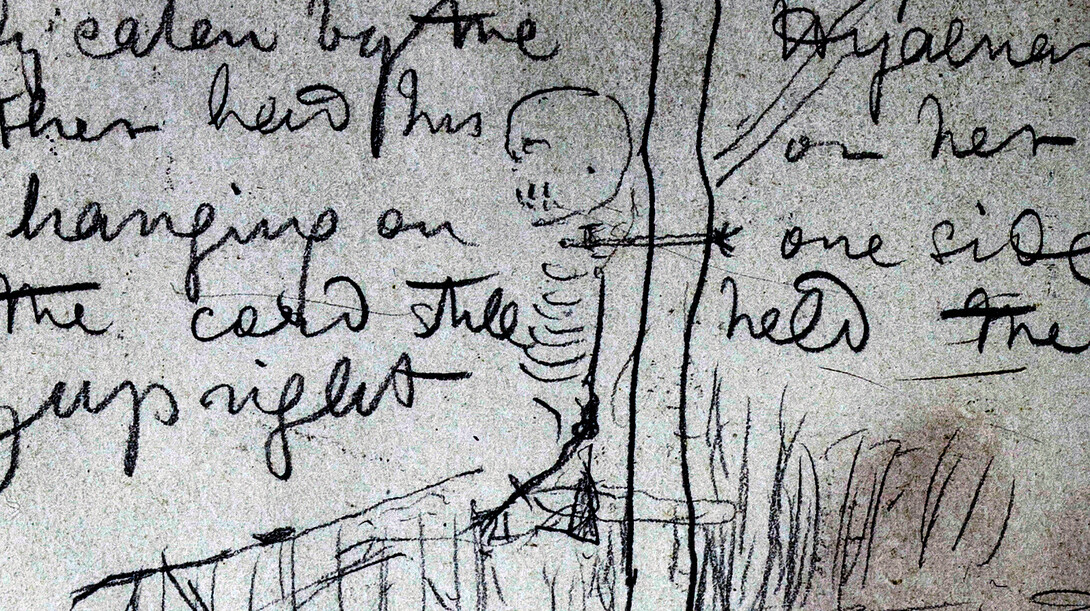

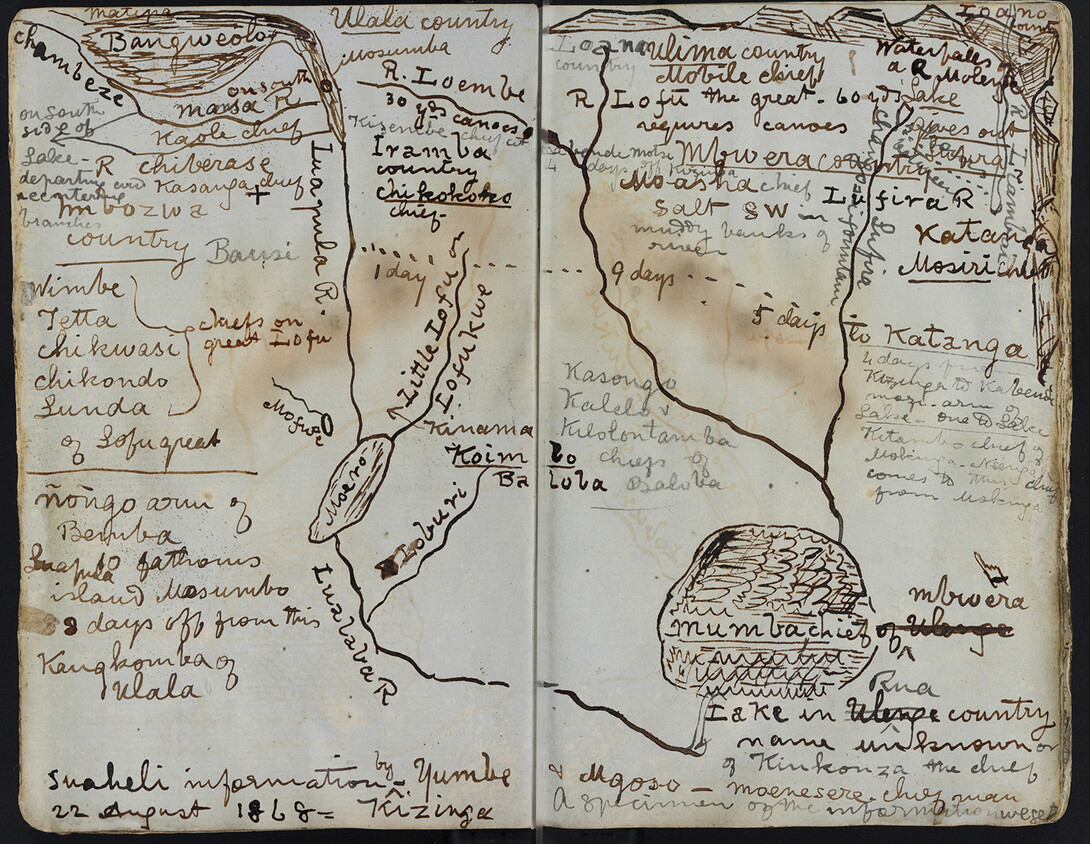

The 19th-century explorer kept these diaries as he embedded himself with slave traders and worked to send information back to Victorian England about the atrocities committed on local African populations. The writings also painted a sweeping picture of the continent — its geography, its environment, its people — before it was colonized.

Now, scholars and the general public can access those pages to gain new insights on the abolitionist and his travels, thanks to the launch of a newly upgraded Livingstone Online.

Livingstone Online has been in existence since 2005, but has been standing still since 2010, when a massive overhaul was started under director Adrian Wisnicki, assistant professor of English and faculty fellow in the University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s Center for Digital Research in the Humanities.

The renovation included extensive research on best website practices and long-term digital preservation. What has emerged is a user-friendly, intuitive platform meant for various audiences.

“It’s very accessible, both to scholars and the general public, and it’s organized in such a way that you can get to the right materials quickly and easily,” Wisnicki said. “We’ve thought about how a modern audience engages with the internet. We’ve also worked with international archival standards so that our site can survive over time.”

Wisnicki said he hopes the site’s transformation also will change how Livingstone’s legacy is interpreted.

“It’s a new way of seeing the past,” Wisnicki said. “It takes all of these documents, which have been scattered in archives around the world, and it brings them all together, so it’s the first time you can see this written legacy — which is otherwise very piecemeal and fragmented — all in one place.

“And when you put all the pieces together, all these things emerge that we never realized before.”

In particular, it focuses on the East African slave trade and how the environment and people in Africa looked compared with rudimentary illustrations in the Victorian press.

“Livingstone’s manuscripts are very complex and they capture information in a wide array of fields,” Wisnicki said. “As a result, they are really important to a wide range of historical, scientific and cultural specialists.”

The site, which began in the United Kingdom under the direction of Christopher Lawrence, professor emeritus of University College London, features contributions from more than 40 international institutions. It contains about 5,000 digitized images of manuscripts with annotated transcriptions. When the project is completed in 2016, it will exceed 10,000 pages.

Wisnicki said the site is also unique in how it approaches the preservation of Livingstone’s legacy. Every process used in the preservation and transcription of the manuscripts is documented on the site.

“It shows you in very detailed ways how a digital humanities project works in the service of representing a legacy like Livingstone’s,” Wisnicki said. “It’s a kind of extraordinary public resource from a scholar’s point of view. This is new to the field.”

Livingstone Online was made possible by grants from the National Endowment for the Humanities and commitments from public institutions.

“We’re working to develop a project that aspires to international standards of transparency,” Wisnicki said, “and that can serve as a model for similar types of projects.”