For millennia, the massive Tibetan mastiff has laid literal claim to the label “top dog.”

The fierce breed, which boasts a lionesque mane and can reach 150 pounds, has long protected Himalayan flocks of sheep from Tibetan wolves and other predators lurking upward of 15,000 feet above sea level — heights no other domestic breed can survive.

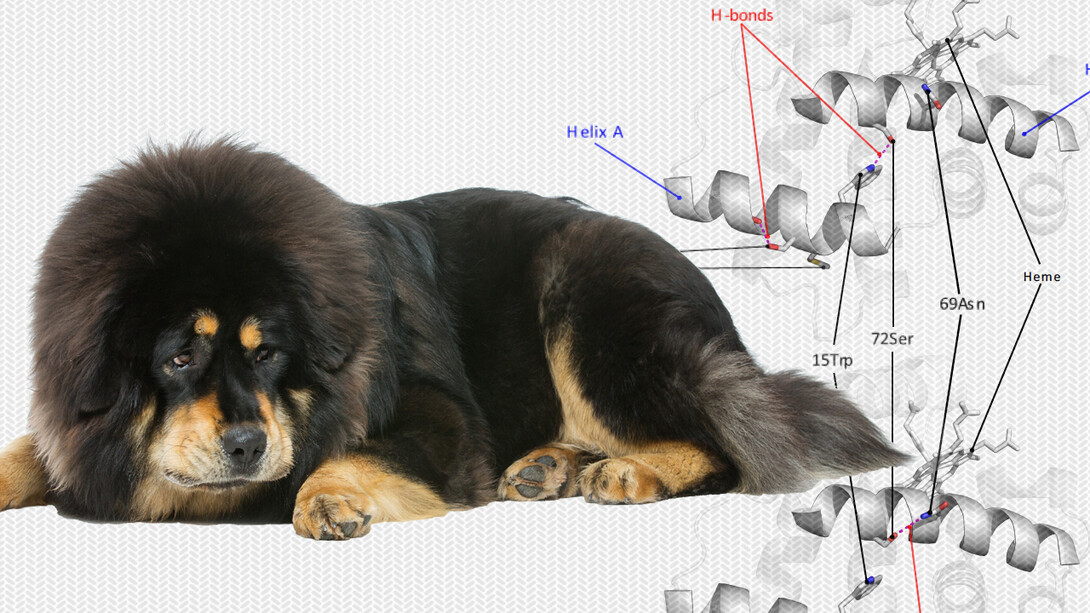

Prior research suggests the Tibetan mastiff took an evolutionary shortcut by breeding with the Tibetan wolf, which had already adapted to the altitude by evolving more efficient hemoglobin: the protein that snares oxygen in the bloodstream and distributes it to organs.

The University of Nebraska–Lincoln’s Jay Storz, Tony Signore and colleagues have now determined that sleeping with the enemy granted the Tibetan mastiff a hemoglobin architecture that catches and releases oxygen about 50% more efficiently than in other dog breeds. Signore reached the conclusion after testing the Tibetan mastiff hemoglobin against that of multiple domestic breeds, including Storz’s own half-Great Pyrenees, half-Irish wolfhound.

“At altitude, the problem is taking in oxygen, because there’s just less of it,” said Signore, a postdoctoral researcher working in Storz’s lab. “If you think of hemoglobin like an oxygen magnet, this magnet’s just stronger.”

The Nebraska researchers, who collaborated with colleagues at Qinghai University in China, already knew that the Tibetan mastiff’s hemoglobin included changes in two amino acids — slight modifications to the structure of the protein — that are present in the Tibetan wolf but absent in all other dog breeds.

By engineering and then testing hemoglobins that contained both amino acid mutations vs. just one or the other, the team discovered that both mutations are crucial to the adaptive change in hemoglobin performance. When either mutation was absent, the hemoglobin performed no differently than that of other dog breeds.

“There had been no direct evidence documenting that, yes, these two unique mutations have some beneficial physiological effect that is likely to be adaptive at high altitude,” said Storz, professor of biological sciences and author of a recent book on hemoglobin. “What we’ve discovered is one of the reasons why the Tibetan mastiff is so different from other dogs. And that’s because it’s borrowed a few things from Tibetan wolves.”

Those two amino acid mutations originate from a gene segment that the Tibetan wolf passed to the mastiff via cross-breeding. But the new study also suggests that the gene segment itself came from an inactive gene — a so-called pseudo-gene — that lay dormant in the wolf subspecies for probably thousands of years. At some point, the pseudo-gene segment harboring the two mutations was copied and pasted into the corresponding segment of a similar but active gene, which then reformatted the Tibetan wolf’s hemoglobin.

Because those mutations came from an inactive gene — one with no physiological effects on the wolf — they weren’t initially subject to the pressures of natural selection. In this instance, though, the mutations just so happened to improve the oxygen-binding capacity of hemoglobin, raising the Tibetan wolf’s survival odds. That encouraged the passage of the gene segment through subsequent generations of the wolf and, eventually, to the Tibetan mastiff.

“They wouldn’t have conferred any benefit under normal circumstances,” Storz said. “It was just (that) this conversion event occurred in an environmental context where the increase in hemoglobin-oxygen affinity would have been beneficial. So mutations that otherwise would have been either neutral or even detrimental actually had a positive fitness effect.”

Storz said there are few other documented cases where an initially inconsequential or adverse mutation ultimately benefited an organism as its environment changed. And most such cases have involved experimental studies on micro-organisms in the lab.

“This is a nice example of the effect involving vertebrate animals and the natural environment,” he said.

The researchers reported their findings in the journal Molecular Biology and Evolution. Storz and Signore authored the study with Nebraska’s Hideaki Moriyama, associate professor of biological sciences, along with Qinghai University’s Ri-Li Ge, Ying-Zhong Yang, Quan-Yu Yang and Ga Qin.

The team received support from the National Science Foundation and the National Institutes of Health under grant No. HL087216.