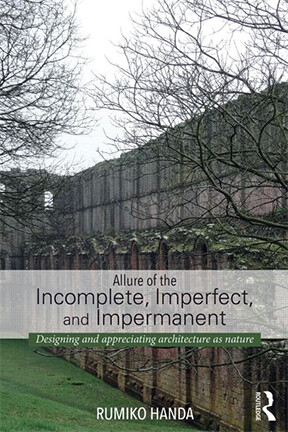

Rumiko Handa, professor of architecture, has released a new book that urges architects to explore the “allure of the incomplete.”

“Allure of the Incomplete, Imperfect and Impermanent: Designing and Appreciating Architecture as Nature” was released Jan. 15 by Routledge.

Handa said architects have long operated based on the assumption that a building is “complete” once construction is finished. But the reality is that changes take place as people move in, requirements change, events happen and building materials are subject to wear and tear.

“I’m finding beauty in the things that are not necessarily perfect,” she said. “Of course, not all imperfect things are beautiful, but I think we need to somehow cultivate our eyes to include these values. A building is not just insufficient or old and irrelevant.”

This project began in 2011 after she co-edited a book with James Potter, professor emeritus, that examined architecture that is portrayed in pieces of literature, arts, theatre and film.

“We wanted to say that architecture contributes to those pieces,” she said. “In thinking about it, it dawned on me that when architecture is playing an important role, that piece of architecture is not necessarily new and pristine and shiny and clean. It’s much more subtle, and maybe dark and dirty. A poet might refer to a ruined cottage and use that as a background in telling a story about this person. There are values of architecture in those pieces that are not necessarily clean, perfect pieces.”

Despite not knowing or being able to control the future of their designs, Handa said architects have some knowledge base for what materials will go through as it decays and about human behavior that they can consider.

“In the past, there were no railroad stations. That was a new building type that came about. The ancient Romans never thought of train stations,” Handa said. “But at the same time, when people congregate, they tend to make a circle. When some figure is revered, that person might stand in a higher position in the room. Those things don’t change. Specific building usage might change, but we should think at the same time that there might be a way of future people adopting what we design for their new purpose.”

Handa wants architects to see their work as nature.

“Architecture is a physical entity, and as a physical entity, it’s part of nature,” she said. “The wood was brought in from a tree. Even if we use plastic, we still make it out of something that is from nature. As such, some aspects of architectural pieces behave like nature—it weathers or it deteriorates.”

At the same time, architecture is used by people.

“But people’s behavior is part of nature,” Handa said. “Birds make nests, and in the same way, people make buildings.”

In the book, she says architects shouldn’t be so decisive in the dichotomy between the natural and the artificial in architecture.

“We might have said that pieces of architecture are artificial because man makes it,” she said. “But maybe we gain something important or useful by blurring that line and considering architecture as nature.”

Her book focuses on three terms: Synecdoche (incomplete), Palimpsest (impermanent) and Wabi (imperfect).

“Synecdoche means a part of something standing for the whole,” she said. “When you look at an old building, maybe the building is not in a complete state so we say it’s in ruins. I use that to describe some of the characteristics as incomplete.”

Palimpsest are the layers of history that might be visible in a building.

“In Medieval times, you’d use the animal hide parchment as writing material,” Handa said. “Because it’s expensive and valuable, you would wash off the old writing and then re-use that for a new writing. But what’s interesting is that when years pass, the old layer shows up, so on one sheet, there are layers of time. In some buildings, there is impermanence. You see the layers of time.”

Finally, “Wabi” is the Japanese concept of imperfection that says there is beauty in the insufficiency of human life.

“Tea masters of the 16th century would make a teacup that is intentionally not perfect,” Handa said. “But because of that imperfection, you actually get to involve yourself much deeper with the teacup. I use that term to discuss imperfection.”

At the same time, Handa said she is not saying that everything imperfect is great and notes that architects cannot control the future of their designs.

“Architects are never fortune tellers,” she said. “It’s not like architects control the future or can foresee everything that will happen to their design. But there has to be some ways that are possible for architects and architecture students to just imagine what this building may become or may be in the future.”