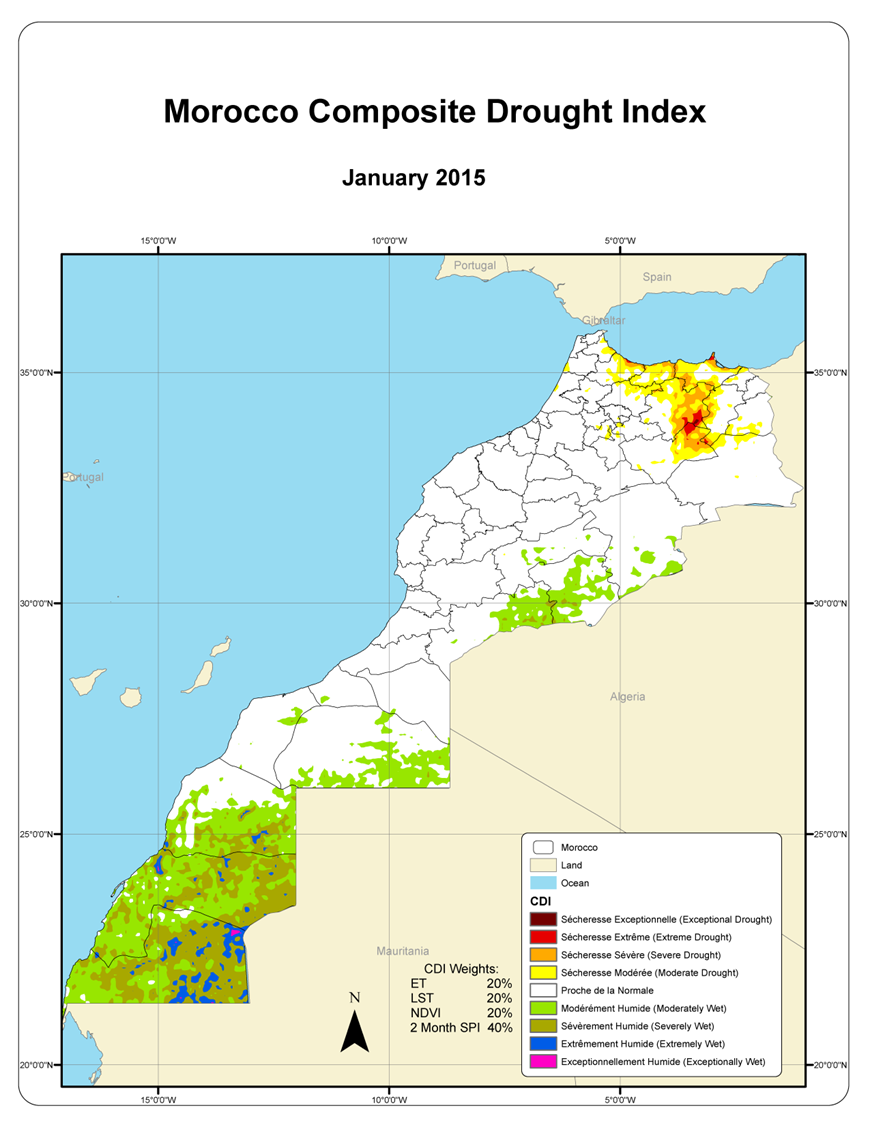

Morocco will have one of the world’s first drought early warning systems that integrate several remotely sensed data sets from NASA and other U.S. agencies into a composite agricultural drought indicator.

The new Moroccan Composite Drought Index was developed with backing from the World Bank and with technical assistance from the National Drought Mitigation Center and Center for Advanced Land Management Information Technologies.

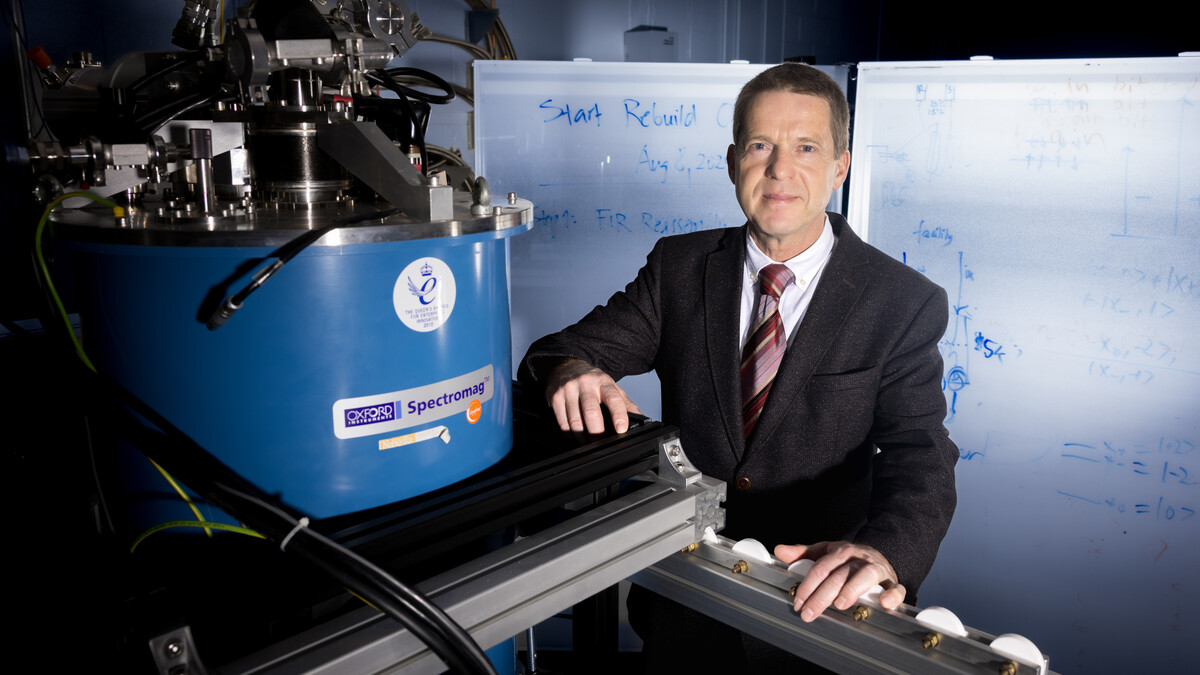

“This is applied earth science research at its best,” said Mark Svoboda, leader of the NDMC’s Monitoring program area. “There are only a handful of systems like this in the world.”

“Over the past decade, a convergence of the satellite-based sensors coupled with improved computing capabilities and modeling approaches has allowed us to make great steps in monitoring agricultural drought,” said Brian Wardlow, director of CALMIT.

“The combined drought index developed in the framework of this project constitutes a new methodology of drought monitoring in Morocco,” said Noureddine Bijaber, with Morocco’s Royal Centre for Remote Sensing. “The added value is that we can monitor vegetation at each 5-kilimeter grid cell every month by combining data on precipitation, soil moisture, evapotranspiration and vegetation condition.”

The new drought index was developed as part of the Land Data Assimilation Systems-Maroc project, designed to improve water resources management in anticipation of a changing climate. Other monitoring systems developed as part of the project focus on irrigated agriculture, water resources and locusts.

“Climate observations during the last 40 years have shown that Morocco is experiencing major impacts from climate change, such as increased temperatures and decreased precipitation,” Bijaber said. “Conditions will get worse based on the projections of the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change.

The main focus of Morocco’s new drought index is to assess conditions in areas used for non-irrigated cereal crops or for grazing. It will mainly be used by government agencies, such as the Moroccan Ministry of Agriculture and the Ministry of Energy, Mines, Water and Environment, but others who may use it include insurance companies, researchers and individual agricultural producers, Bijaber said. One of the next steps will be for the ministries to compare historic values from the computed composite index with data such as actual crop production so that the project team can fine-tune the blends of data if needed.

As in other African countries, in situ data – observations recorded for a given location – are fairly sparse across Morocco, Svoboda said. He and Wardlow worked with Chris Hain, an atmospheric scientist at the University of Maryland, to identify satellite-derived data that would work for these purposes. They came up with four different indicators based on three data streams from NASA and one from a coalition of U.S. agencies.

The team worked with a local validator, Yessef Mohammed, at the Hassan II Institute of Agronomy and Veterinary University, to develop a weighting scheme for blending the four indicators into a composite drought index. The indicators include: the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index Anomaly and Evapotranspiration Anomaly, both generated by the U.S. Geological Survey’s Famine Early Warning Systems Network, and Land Surface Temperature-based soil moisture input produced by NASA, and a two-month Standardized Precipitation Index, based on the multi-agency Climate Hazards Group InfraRed Precipitation with Station data.

NDMC spatial analyst Chris Poulsen crunched the data for each of the four inputs, as well as the MCDI, for each of the 26,000 grid points, and delivered the results, complete with database, code and script, to his Moroccan counterparts. The NDMC led production of the new MCDI for January and February.

Once the validator completes his work and the methodology is completely fine-tuned, the drought composite index will be produced monthly from October to April of each year, Bijaber said.

Over the course of the project, various U.S. team members made three trips to Morocco, and Moroccan counterparts made one trip to the NDMC for training. In late February, Svoboda and two U.S. university colleagues traveled to Rabat and held a workshop for about 40 stakeholders, mostly from various Moroccan ministries, but with representation from other countries in the Middle East-North Africa region and from NASA.

“The technical assistance from the experts with the University of Nebraska and the University of Maryland, led by Mark Svoboda, was very helpful,” Bijaber said. “We appreciate this know-how transfer and we are thankful for the cooperation and help of each expert.”