From color photographs by Gordon Parks in the 1950s that document the social and economic impact of racism, to Robert Colescott’s large-scale painting “The Other Washingtons,” to works produced in 2015 by Nathaniel Mary Quinn and Leonardo Drew, Sheldon Museum of Art’s recent acquisitions advance an ongoing commitment to collecting works that reflect cultural diversity and global connectedness.

“The works acquired in 2015 contribute greatly to Sheldon’s mission as an academic art museum,” said Wally Mason, director and chief curator. “They enable us to further build and exhibit a collection that mirrors the time in which we live. The museum is a resource for students, faculty and visitors in the exchange of ideas on contemporary aesthetic and social issues.”

Augmenting its holdings in documentary photography, Sheldon has acquired two photographs by Parks, who is remembered for the commitment to social justice with which he reported American culture from the 1940s until his death in 2006. As part of a series commissioned by Life magazine in 1956 to chronicle the daily activities of families living in the Jim Crow South, the photographs provide a record of the social and economic impact of racism.

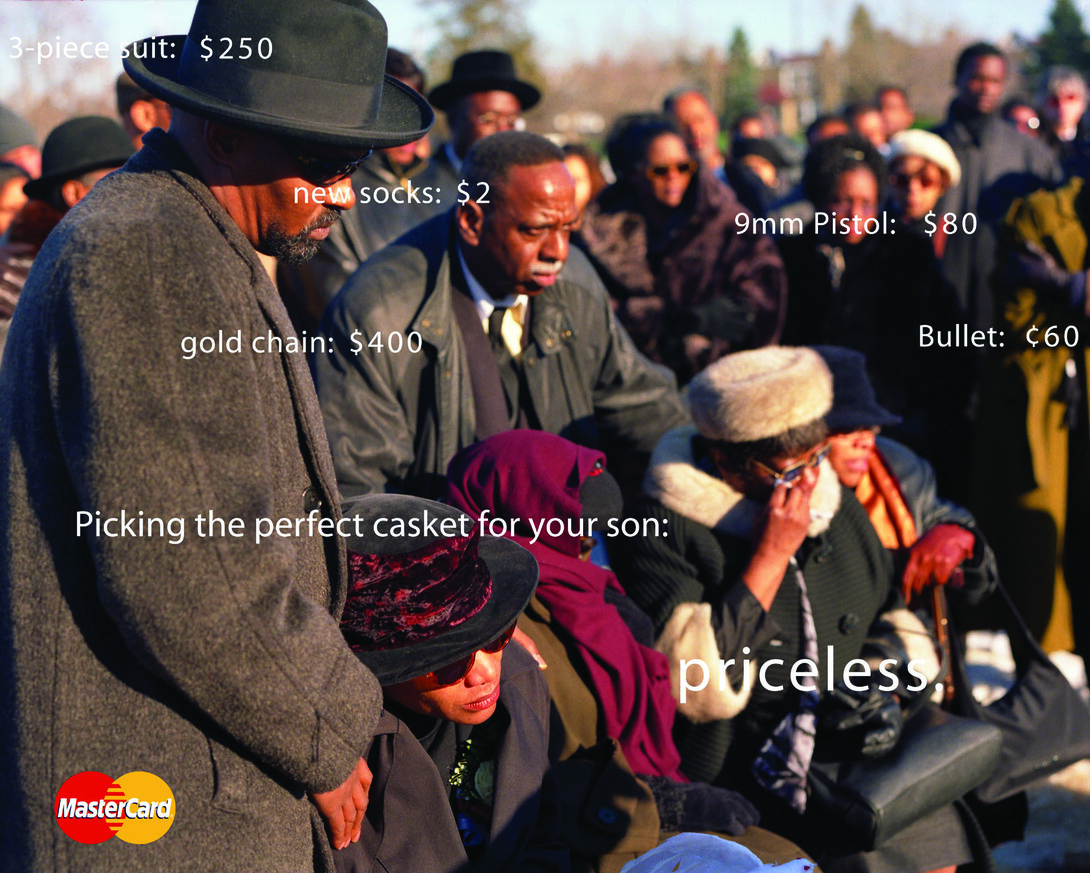

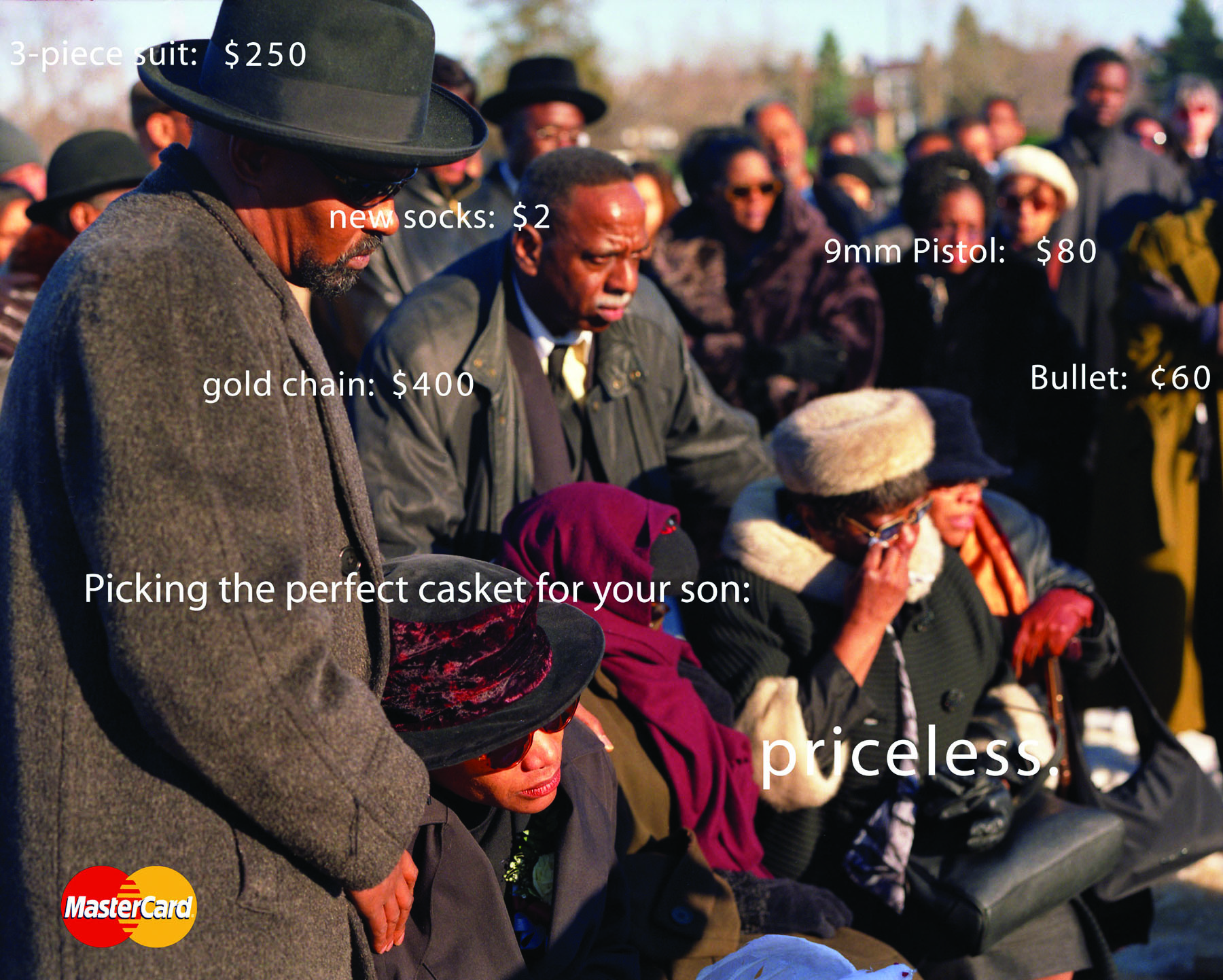

Matthew Sontheimer, assistant professor of art at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, sees the museum’s recent acquisitions as catalysts for dialogue across departments and areas of study at the university. He cites “Priceless #1” by Hank Willis Thomas as a work that inspires discussion of contemporary issues.

Formative to Thomas’ career, “Priceless #1” is a significant acquisition for the museum. The artist began the work, which references MasterCard advertisements, with a photograph he made at the funeral of his cousin who was murdered during a violent robbery in 2000. Sontheimer proposes a question he would ask students about the work: “How do you read this image when I tell you it is not a staged photograph?”

The museum purchased another provocative photograph, “Cotton Bowl,” made by Thomas in 2011. The image depicts a football player in a three-point stance at a goal line facing a man in a similar stance picking cotton in the end zone. Acquired in a year in which a major university football team threatened to forfeit a game in solidarity with students protesting systemic racism on their campus, “Cotton Bowl” demonstrates the power of an artwork to serve as a catalyst or resource in public discourse.

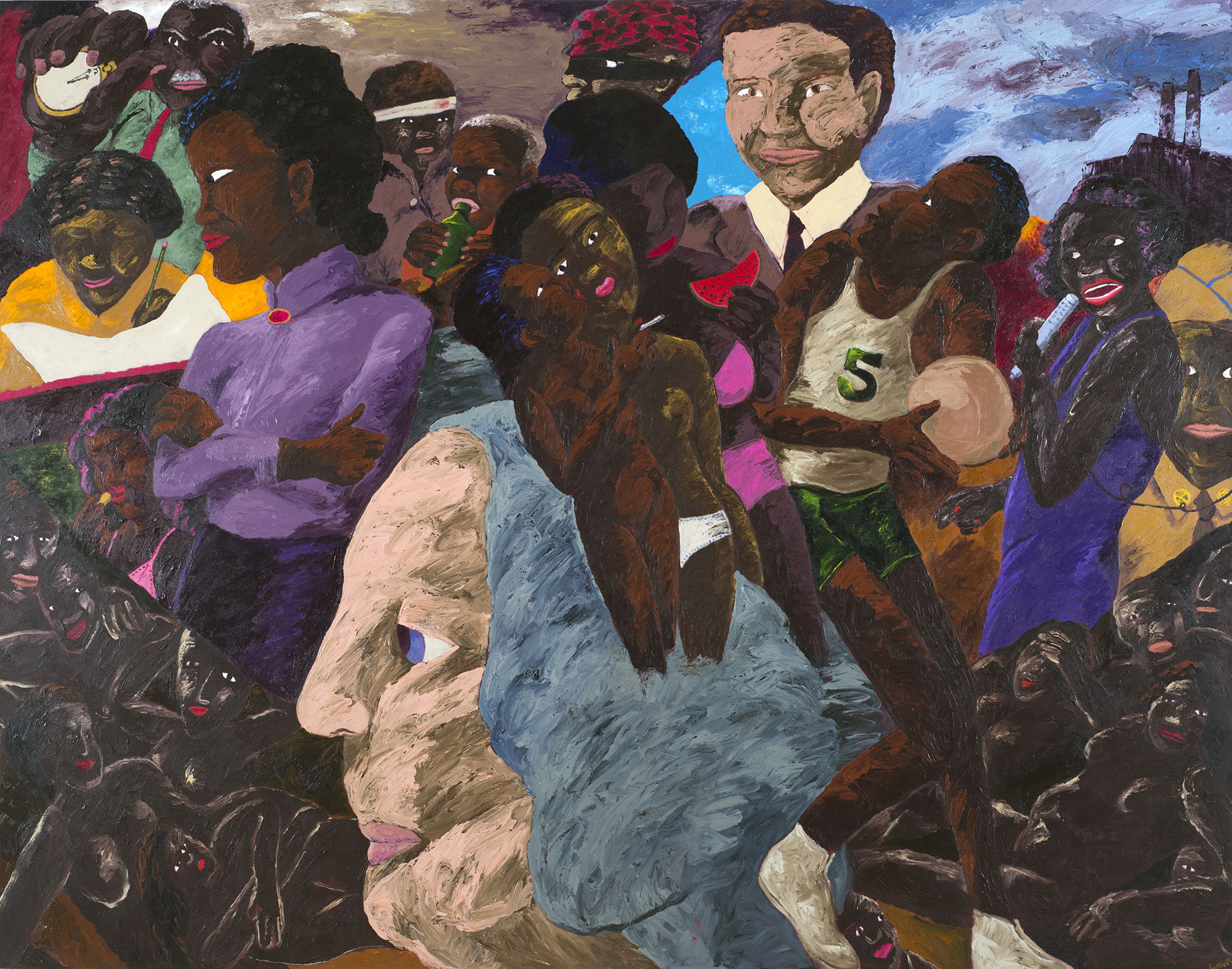

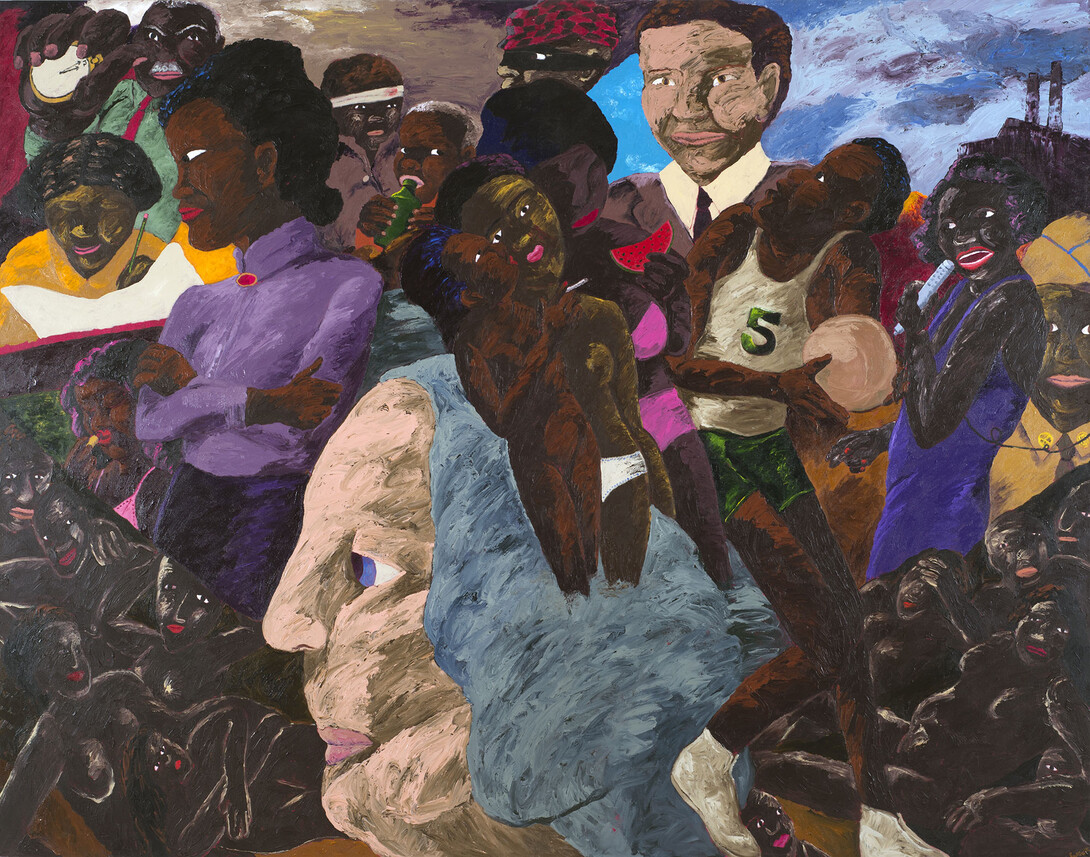

Colescott, whose work employed satire, observation and painterly technique in equal parts, produced canvases that address historic and social issues including racial and sexual stereotypes. Sheldon has acquired Colescott’s “The Other Washingtons,” created in response to U.S. Census data that showed 90 percent of people with the surname Washington shared African-American heritage.

Other works created recently by artists Willie Birch, Drew and Quinn impart references to the hope and renewal that exist in the aftermath of destruction.

“Number 175T,” a muscular work by Drew, emerges from the museum wall as a dense thicket that simultaneously implies deterioration and resurrection. Although the elements in Drew’s work are often mistaken for found objects, they are new materials subjected to multiple, often destructive, processes. Diagrammatic and suggestive of rebirth within decay, the work carries metaphorical and historical weight.

In his large-scale charcoal drawings, Birch conveys the energy, cultural diversity and everyday rhythm of his native New Orleans. Birch, a founder of The Porch, a neighborhood organization to build cohesiveness in the aftermath of Hurricane Katrina, seeks to express the dignity and perseverance of his subjects. His narrative drawing suite “Sweeping, Scrubbing, Washing, Healing” communicates these characteristics in a depiction of a community’s reaction to a violent death.

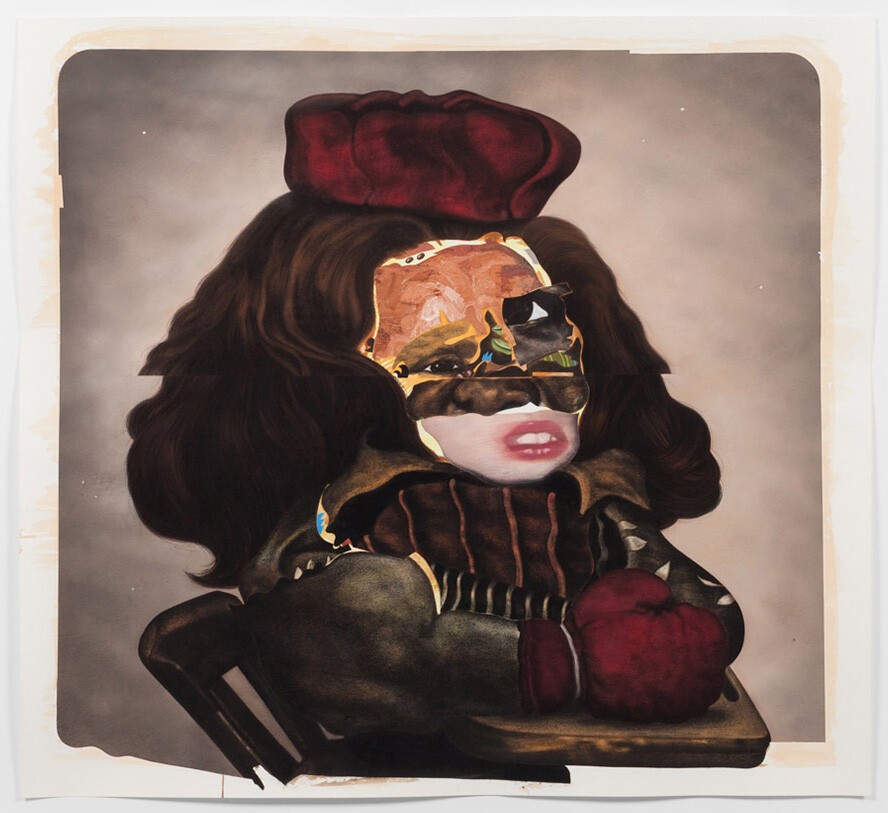

Sheldon has also purchased a portrait by Quinn that exemplifies the artist’s technique of combining media – including charcoal, soft pastel, oil pastel, oil paint, paint stick, acrylic silver leaf and gouache – to convey the complex identities of his subjects. Compelling in their grotesque exaggerations, Quinn’s portraits recall childhood experiences, both good and bad, that have formed his humanity and current disposition.

Sheldon acquisitions extend the museum’s collection beyond the walls of its landmark Philip Johnson building. More than 30 monumental-scale artworks are installed throughout the 624-acre UNL campus. In July 2015, a hand-painted fiberglass sculpture by Yinka Shonibare, which captures the movement of thin cotton fabric billowing from a bolt, was installed at UNL. The form of the 20-foot-tall sculpture references the sails of the ships that once transported mass-produced fabrics from Southeast Asia to Dutch colonies in Africa, expressing the complexity of cultural and national identity within contexts of globalization.

Other notable acquisitions from the past year include five drawings by Mary Henry; photographs by Ansel Adams, Jim Dow, Mark Ruwedel and John Divola; a major painting by Dan Christiansen; and several works by alumnus Bruce Conner. A selection of images of works acquired in 2015 is available at http://go.unl.edu/new-art-2015.

Sheldon Museum of Art, which houses a permanent collection of more than 12,000 objects, is located at 12th and R streets on the UNL City Campus. The museum is open free to the public during regular hours: Tuesday, 10 a.m. to 8 p.m.; Wednesday through Saturday, 10 a.m. to 5 p.m.; Sunday, noon to 5 p.m. The museum is closed on Mondays. For more information, click here.