How can you snap a picture of a burst of electrons traveling at nearly the speed of light?

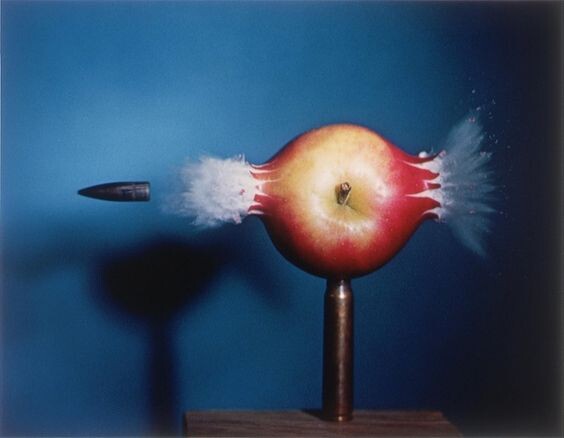

Time-lapse strobe photography – a technique that shines a short flash of light onto an object – was famously used to freeze a speeding bullet in time as it punctured an apple. This same technique can, in principle, be used to capture electrons in mid-flight. Because electrons travel a trillion times faster than bullets, however, the duration and timing of the corresponding light flash must also be a trillion times shorter.

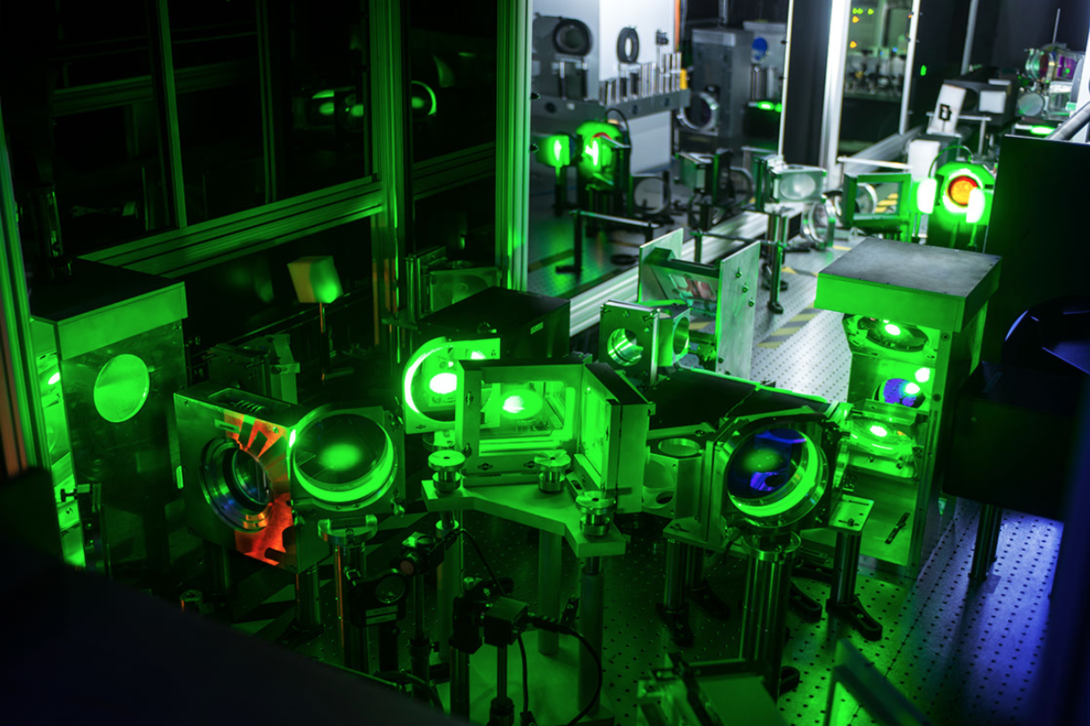

As recently reported in the journal Scientific Reports, an international team led by UNL physicists has achieved this feat by using two light pulses from a laser system developed at UNL’s Extreme Light Laboratory. One pulse generated the electrons, with the other acting as the strobe flash. This two-pulse laser method guaranteed perfect synchronization between the arrival of an electron burst and light flash that each lasted just a few femtoseconds, the study reported. A femtosecond compares to a second as a second compares to about 31.7 million years.

The technique also showed that an electron-accelerating technology developed by UNL physicist Donald Umstadter and colleagues in 2013 – a technology crucial to the design of portable X-ray sources – compares favorably with conventional electron accelerators.

“This new technique will allow us to follow the dynamics of other ultra-fast processes and reactions,” said Umstadter, the Leland J. and Dorothy H. Olson Chair in Atomic, Molecular and Optical Physics. “The improved physics understanding gained in this way will advance research and development in energy, biomedicine, security and defense.”

Umstadter co-authored the study with Grigory Golovin, senior research associate of physics and astronomy; Sudeep Banerjee, research associate professor of physics and astronomy; Cheng Liu, senior research associate of physics and astronomy; Shouyuan Chen, research assistant professor of physics and astronomy; postdoctoral researchers Jun Zhang, Baozhen Zhao and Ping Zhang; and researchers from the Rutherford Appleton Laboratory in the United Kingdom.

The researchers received support from the National Science Foundation, U.S. Department of Energy, Air Force Office for Scientific Research and Department of Homeland Security.