A pivotal second year of college put Andrew Benson on a cutting-edge research path that has explored bacterial spores, aquatic bacteria, pathogens and gut microbes.

After coasting through high school in Ankeny, Iowa, and finishing his freshman year at Iowa State University, Benson was at a crossroads. Due to the downturn in the farm economy in the 1980s, Benson’s family was leaving Iowa for better opportunities in Texas. Benson opted to stay behind to continue college and be with his high school sweetheart and fiancé (now wife), Renee.

“It became apparent that it was time to become the master of my own destiny,” Benson, a microbiologist at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, said. “All I needed to do was find something that I liked and pour myself into it.”

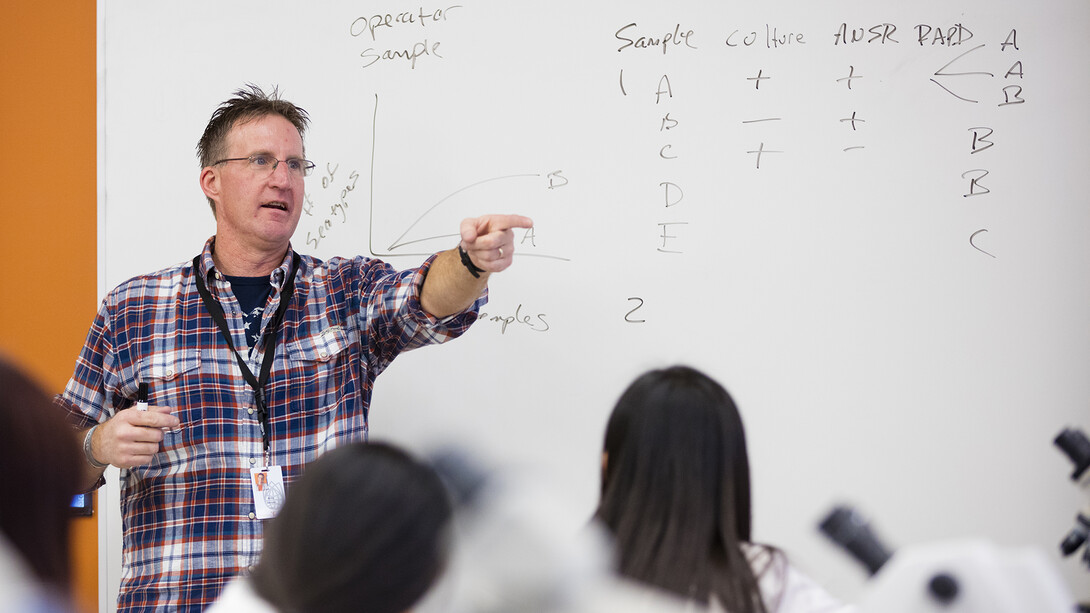

Alongside the normal second year slate of classes, Benson enrolled in a microbiology course normally reserved for juniors and seniors. While the work was challenging, he became enthralled with the diversity and complexity of the organisms discussed.

“I knew almost right away that this was what I wanted to do for a career,” Benson said. “I’m a visual, pattern-oriented guy. I loved studying these organisms and seeing and understanding the patterns within them.”

Benson has been a UNL faculty member since 1996 and is currently the W.W. Marshall Distinguished Professor of Microbiology.

In two decades of research, Benson has become an expert in genomics, applying genome-based technology to microbes that can invade the digestive tract as well as those that are involved in gut health. He is a highly sought expert for litigation of foodborne illnesses across the country. Also during his tenure, Benson helped found the UNL Gut Function Initiative and recently launched a startup company.

Benson will discuss his recent research into the understanding of digestive tract microbes and its future direction during the spring Nebraska Lecture at 3:30 p.m. April 20 at the Nebraska Innovation Campus Conference Center, 2021 Transformation Drive. The lecture is free and open to the public. For more information, click here.

Back when he was an undergraduate, Benson paid for his degree primarily by working as a technician in the laboratory of Paul Hartman in the microbiology department at Iowa State. Hartman and graduate students in his laboratory served as mentors, helping further Benson’s transformation into a researcher.

Graduating with a bachelor’s degree in microbiology, Benson already had his name on two published research papers from the diagnostic microbiology he completed in Hartman’s lab and molecular genetics projects he worked on in the lab of Peter Pattee.

“Undergraduates rarely were included in research back then,” Benson said. “The work at Iowa State really set the stage, giving me a skill set and experience that many undergraduates didn’t have at the time.”

Benson spent graduate school at the University of Texas, earning a doctorate in microbiology while studying bacterial spores in a lab led by William Haldenwang. Benson also served as a postdoctoral fellow at Princeton University, researching Caulobacter crescentus, an aquatic organism that is studied as a model for the bacterial cell cycle. Through those years, Benson was growing his portfolio of techniques in the rapidly moving field of molecular biology.

As he neared the end of the Princeton fellowship, Benson became interested in applying the tools of molecular biology to real-world problems and was intrigued by a very new trend for such tools in food microbiology. He reached out to former Iowa State colleagues Charles Kasper and John Luchansky, who were in the field and working at the University of Wisconsin.

“At that time, molecular biology was just beginning to hit the food science arena,” Benson said. “They thought the position in Food Science and Technology at UNL would be a good match for my skill set and encouraged me to go for it. I sent applications to UNL and a couple of other places and the phone literally ring off the wall.”

For his UNL interview, Benson developed a research seminar describing how one would use the tools of molecular biology to examine a spore-forming bacterium (Bacillus cereus) that can cause two different types of food-borne illnesses. The presentation integrated work Benson completed as a graduate student studying spore biology at the University of Texas.

“My post-doctoral adviser at Princeton was shocked that I wasn’t doing some intense, focused seminar on the beautiful temporal-spatial patterns of gene expression I had discovered in Caulobacter,” Benson said. “But I thought it was far more important to do something that would resonate with food science faculty here at UNL. It was a bold and risky move on my part, but I enjoyed the challenge of thinking about taking on a real-world problem.

“And, I guess it worked because here I am.”