As the enrollment of Husker chemistry students began climbing, Jody Redepenning understood that the number of hoods and sashes would need to increase in kind.

But the professor and department chair of chemistry wasn’t thinking regalia. The hoods and sashes on his mind: the time-honored exhaust systems and accompanying windows that collectively remove hazardous fumes stirred up in the standard organic chemistry lab.

When Redepenning saw the Department of Chemistry outpacing even the marked growth of many peers across the university, he realized it was past time to optimize the lab space and resources available in its longtime home, Hamilton Hall. There was also the not-insignificant fact that the “senior” label applied to more than just students taking classes in the venerable nine-story tower.

“This building is 50 years old, and a 50-year-old undergraduate lab is an old lab,” Redepenning said. “It needed to be done.”

Accordingly, the Department of Chemistry is now two-thirds of the way through a three-phase, $12 million renovation project that is again putting its undergraduate labs on par with those at other top-flight, research-intensive universities.

“This gets us where we need to be in terms of safety and the ability for students to practice modern techniques of doing organic chemistry,” he said.

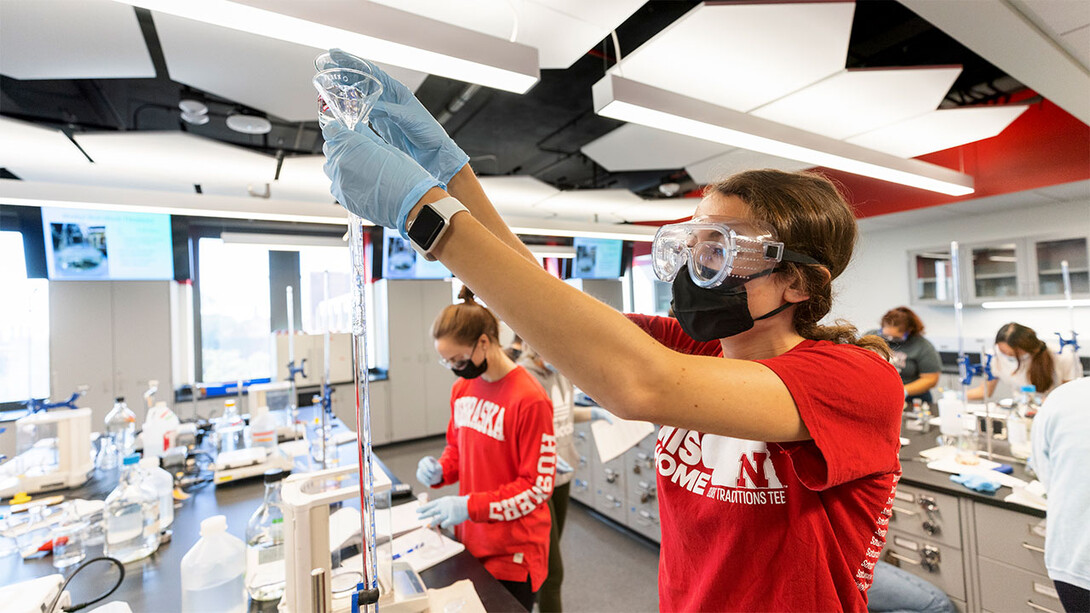

The bright, gleaming, newly renovated labs reside on Hamilton’s third and fourth floors, where they accommodate roughly 500 organic chemistry students, but also substantial numbers taking introductory, inorganic and analytical chemistry courses.

“It used to be a situation where, with organic chemistry, there would be two to three hoods for 15 to 20 students,” Redepenning said. “Now there’s one hood for every two students. Student pairs are able to set up their glassware in the hood and perform complex manipulations while maximizing lab safety. The labs are also much bigger.”

Because the project didn’t call for expanding Hamilton’s architectural footprint, going bigger has often meant tearing down, and leaving down, the barriers between existing lab spaces. (“Removing walls is not just a metaphor here,” Redepenning said.) The largest of the new fourth-floor spaces — which can house groups of organic, inorganic and analytical chemistry students simultaneously — used to comprise three separate labs.

That open floor plan, combined with the three-phase approach to construction, is also part of a strategy that Redepenning and his colleagues have adopted to win what he described as a “shell game.” The prize? Minimizing disruptions by ensuring that all of the chemistry credit-hours normally available to students would continue to be.

About 55% of those credit-hours are offered in the fall, with the remaining 45% in the spring. What initially seemed like a fairly even distribution, though, turned out to be a sizable difference when looking at the numbers from a different perspective. Those numbers showed that the department was offering nearly one-quarter more credit hours in the fall semester than the spring.

“We were so close to the margins in terms of capacity, we knew that we couldn’t do the renovation in the fall without sacrificing credit-hours,” Redepenning said.

So the team commenced the project’s first phase immediately following finals in December 2019, then did the same with the second phase in December 2020. Noisy demolitions were relegated to those times when only faculty and staff were in the building, with the COVID-19 pandemic temporarily extending that quiet period in 2020.

By reconstructing the Hamilton spaces one phase at a time, while transforming those spaces into more open layouts, the department found that it could continually shift students from under-construction labs to larger, newly available ones — à la, the shell game.

“By many measures, it would be easier to just do the whole thing at once, but that would sacrifice student credit-hours. I believe we’ve been able to do it without any of that, which involved many shells and many peas moving around in a certain fashion,” said Redepenning, who credited staff members Peg Bergmeyer, Jessica Periago and Dodie Eveleth with keeping the peas in shells and shells on the table. “Last spring was probably the most challenging time in terms of the bottleneck and how we had to move things around, and I think we’re past that now.”

The equipment and infrastructure now populating those renovated spaces also rate as upgrades, he said. The new fume hoods transport air with less turbulence, reducing both noise and the chances of trace vapors or nanoparticles hanging around the labs. And the staggered configuration of those hoods — designed to maximize real estate for students, even as it allows the department to fit more hoods in equivalent space — also happened to augment their overall airflow.

“There are lots of reasons to feel good about this,” Redepenning said of the renovation, adding that, though first-year Huskers might not grasp the magnitude of the upgrades, “Those students who had organic chemistry in the old space and have now moved to the new space — they get it.”