Welcome to Pocket Science: a glimpse at recent research from Husker scientists and engineers. For those who want to quickly learn the “What,” “So what” and “Now what” of Husker research.

What?

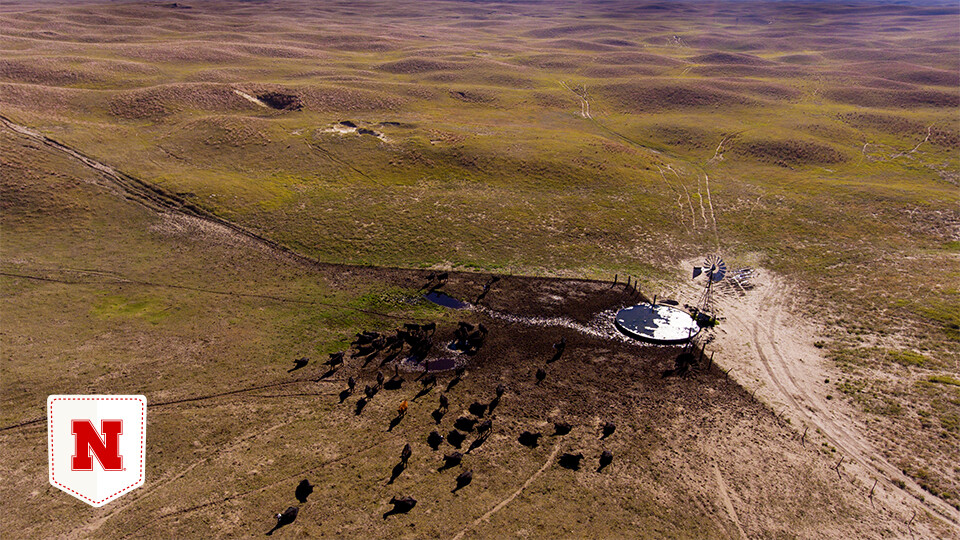

The challenge of converting grassland plants into enough beef and dairy to feed a still-growing population — without degrading soil quality or plant composition — is one ranchers continuously face.

Beginning in the 1980s, some ranchers adopted a practice called mob grazing: increasing the density of livestock in a given space, cycling those dense herds through multiple pastures a day, then giving the pastures extra time to recover. In the process, the thinking went, herds would trample more standing plants, recycling more nutrients and ultimately yielding healthier soils that increased both plant and livestock production. But the science behind mob grazing remains unsettled.

So what?

Nebraska’s Bianca Andrade, Walter Schacht and colleagues recently concluded the longest-ever replicated study of mob grazing. Over an eight-year span, the team compared the practice — 36 steers rotating twice a day through a total of 120 sub-irrigated pastures during the Nebraska Sandhills’ growing season — against approaches in which nine steers rotated through four larger pastures just once every 10 or 15 days.

The team found that mob grazing led to the trampling of roughly half the standing plants, nearly double that of the conventional four-pasture rotations. Even so, the researchers measured no meaningful differences in the subsequent production, composition or root growth of pasture plants.

In fact, the percentage of available grasses consumed by the steers was generally lower in the mob-grazing condition. Probably as a result, those steers actually gained less weight — in some years, just one-fourth as much as their conventionally grazing counterparts.

Now what?

The team concluded that the purported benefits of more trampling are, if anything, limited. Ranchers might consider initiating mob grazing earlier in the growing season — when plants are leafier and more likely to be eaten — and introducing a second grazing cycle in the summer, the researchers suggested.