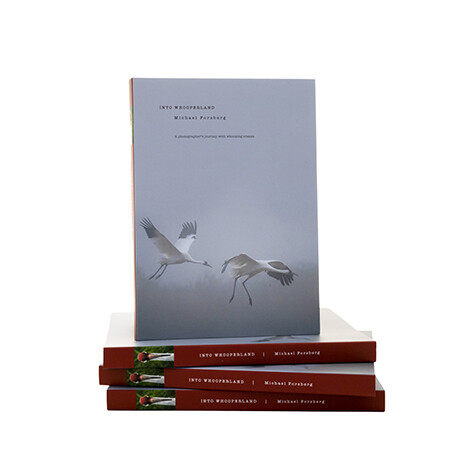

Michael Forsberg, a research assistant professor and conservation photographer-in-residence in the School of Natural Resources at the University of Nebraska-Lincoln, self-published a book on the lives of North America's rarest crane species last month.

Photos and essays show the whooping cranes' nesting, wintering and 2,500-mile annual migration from northern Canada to the Gulf of Mexico. The migration route crosses Nebraska, but images were taken all along the migration route

Whooping cranes are 5-feet tall and bright white with black wingtips spanning 8 feet, and they are the tallest bird in North America.

In the late 1940s, there were just 16 whooping cranes left in the world. Intensive conservation work has brought the species, Grus americana, to a population of about 850, inclusive of wild, experimental and captive populations. The cranes’ comeback is a guarded success, achieved through multistate efforts of hundreds if not thousands of conservationists, biologists, environmental activists, policymakers and bird enthusiasts. They are a symbol of the conservation movement and offer hope for other species of concern.

“Into Whooperland,” is available for purchase on his website. The book is also available in limited numbers at Francie and Finch, 130 S 13th Street. An accompanying website and podcast can be found online.

Forsberg is a nationally known photographer who first established his reputation in Nebraska photographing sandhill cranes and Great Plains wildlife. He’s also co-founder of the Platte Basin Timelapse, a project housed in the School of Natural resources that documents the Platte River and its associated environs in Nebraska, Colorado and Wyoming.

He undertook the project independently from the university, with some private donations and other funding sources.

A cornerstone of Forsberg’s project was to follow the cranes’ migratory flyway, starting along the Texas Gulf Coast where they winter and flying by small plane north to Wood Buffalo National Park in northwestern Canada.

“Typically, stories on whooping cranes primarily focus on either Texas or Wood Buffalo,” Forsberg said. “I wanted to connect the dots of their migration up the middle and emulate their journeys as well as focusing on the landscape below.”

Forsberg estimates he made more than 100,000 still photos, captured 50 hours of video, and spent roughly 200 days in the field in the U.S. and Canada with crane biologists, habitat managers, private landholders, tribal members, and other self-described “craniacs.”