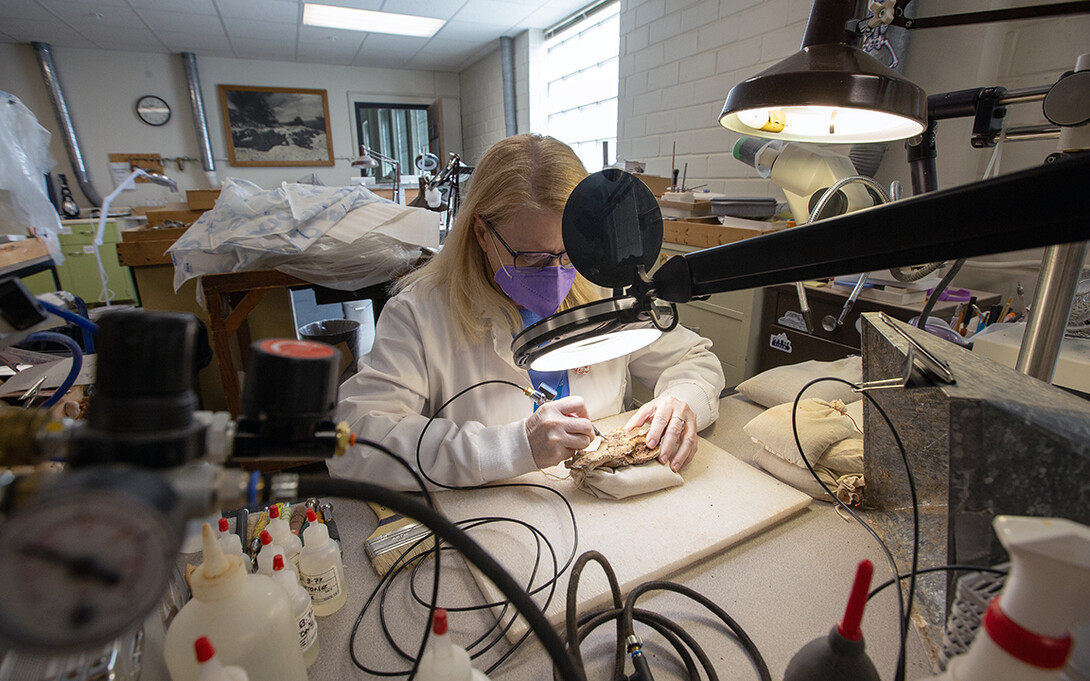

The high-pitched buzz of an air scribe drifts through the hallways at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln, leading to a lab where Carrie Herbel leans over a fossil that predates humanity by millions of years.

She gently flips the specimen, a crushed skull of an early ancestor to modern mammalian carnivores, still bound by sediment to other fragile fossils. Part of a scapula, sharp and protruding. Shattered fragments. All layered atop a row of ancient teeth waiting to be revealed for further study.

With steady hands and sharp focus, Herbel plans her next steps — removing the hardened stone, stabilizing the structure, preserving what time and earth have nearly erased.

“In a way, this work is bringing something back to life,” Herbel said. “Every bone has a story to tell — we just need to find it.”

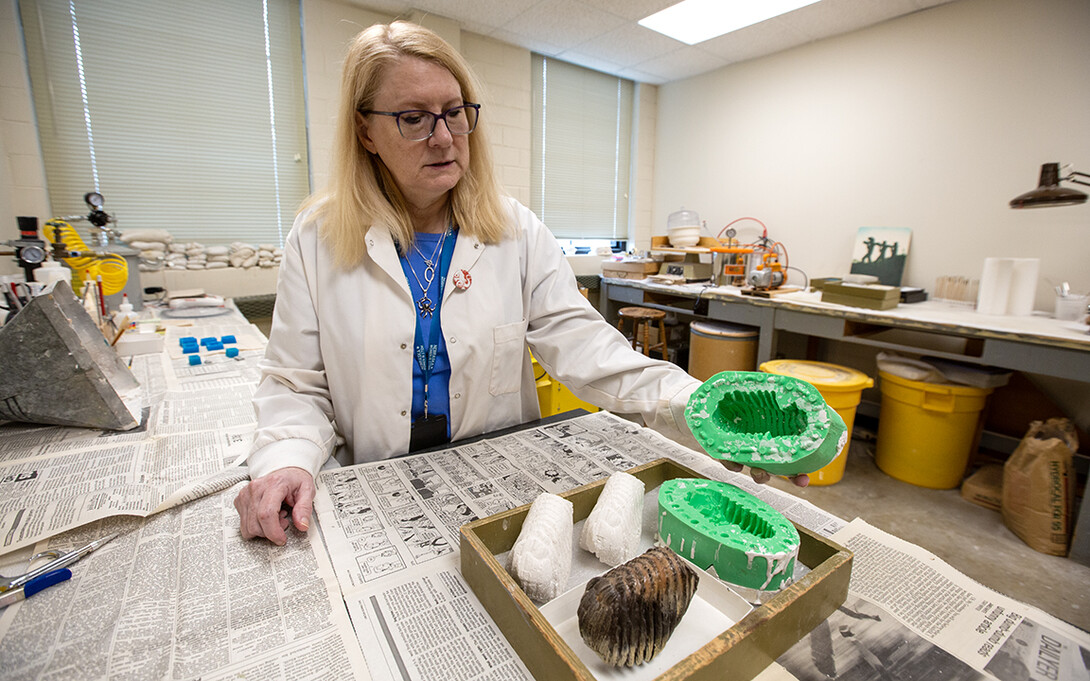

As the chief preparator at the NU State Museum, Herbel has spent the last decade immersed in this work, restoring, conserving and sometimes reassembling bones pulled from deep time. Some are destined for museum exhibitions. Some land in research drawers, waiting for future study. Others become casts or molds used in traveling educational kits for schools and outreach.

Today, she is one of the more than 900 University of Nebraska–Lincoln employees who will be honored for their years of service. The ceremony is 11 a.m. to 1 p.m. at the Coliseum. A free lunch will be served.

It’s not a career path she planned for when she enrolled at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln. Like many Huskers, she arrived with a mix of interests and eventually settled on civil engineering. But a general science requirement — a class on elephants of the Great Plains, taught by Mike Voorhies, the paleontologist who discovered Nebraska’s Ashfall Fossil Beds — changed everything.

“That class sparked my interest and led me into a career in paleontology,” Herbel said. “Mike is the one who got me into all of this.”

After earning her undergraduate degree, Herbel stayed at Nebraska U to pursue graduate work with Voorhies.

A second mentor, longtime museum preparator Greg Brown, gave her hands-on training in fossil conservation techniques. She learned how to safely separate bone from matrix, stabilize delicate specimens and tackle even the most chaotic projects — like removing old adhesives and other interesting items from the tangled neck of a fossilized plesiosaur on display under glass in Morrill Hall's Mesozoic Gallery.

“You would not believe what was shellacked into that plesiosaur neck,” Herbel said. “Toys, old glue — it took months to clean. But it turned out really good.”

Though Brown prepared the skull, Herbel took on the neck vertebrae — work that pushed her skills and grew her confidence.

“I was pretty good at what I was doing because of Greg,” she said.

After Nebraska, Herbel worked as a preparator at the South Dakota School of Mines and the Prehistoric Museum at Utah State University, gaining experience with different fossil types and preparation environments.

Eventually, she stepped away from the field to care for her mother in Arizona. She still felt the pull of fossil work — and her mom noticed it, too.

“Mom urged me to get back into museum work,” Herbel said, glancing at a line of doll faces that adorn her workstation, a gift from her mother. “Because, she said, that was when I was happiest.”

In 2015, a job listing brought her back. Brown had retired from the NU State Museum and his position as a preparator was open — a full-circle moment that allowed her to take a position once held by her mentor.

“I’m a Nebraska girl,” she said. “I was born in Seward, lived in Omaha, Hastings and Lincoln. Other than the humidity, I’ve never regretted coming back to Nebraska.”

She now oversees fossil prep across the museum’s vast collections, including a significant archive of unprepared specimens. Thousands of bones — some still in plaster field jackets — have passed through her hands. Under her leadership, more than 1,400 fossils have been stabilized for future study or display.

That includes one of her biggest challenges: a titanothere (also known as brontothere) skull that sat in a 600-pound block of rock before Herbel carefully freed it from the surrounding matrix. The work took more than a year, and the specimen is featured in Morrill Hall’s "Cherish Nebraska" exhibition.

She continues to train student interns and volunteers in the lab, just as her mentors once did for her. She teaches them how to respect each bone, to work slowly, to do no harm.

Herbel never saw herself in this role when she walked into that random geology course. But, the buzz of her air scribe has become the soundtrack of a career built from patience, curiosity and deep care.

“Time flies,” she said. “It feels like I just started. But I’ve come home — and I haven’t regretted it.”