Nebraska’s Margaret Huettl is helping erase stereotypes and expand historical accuracy through an update to the classic Oregon Trail video game.

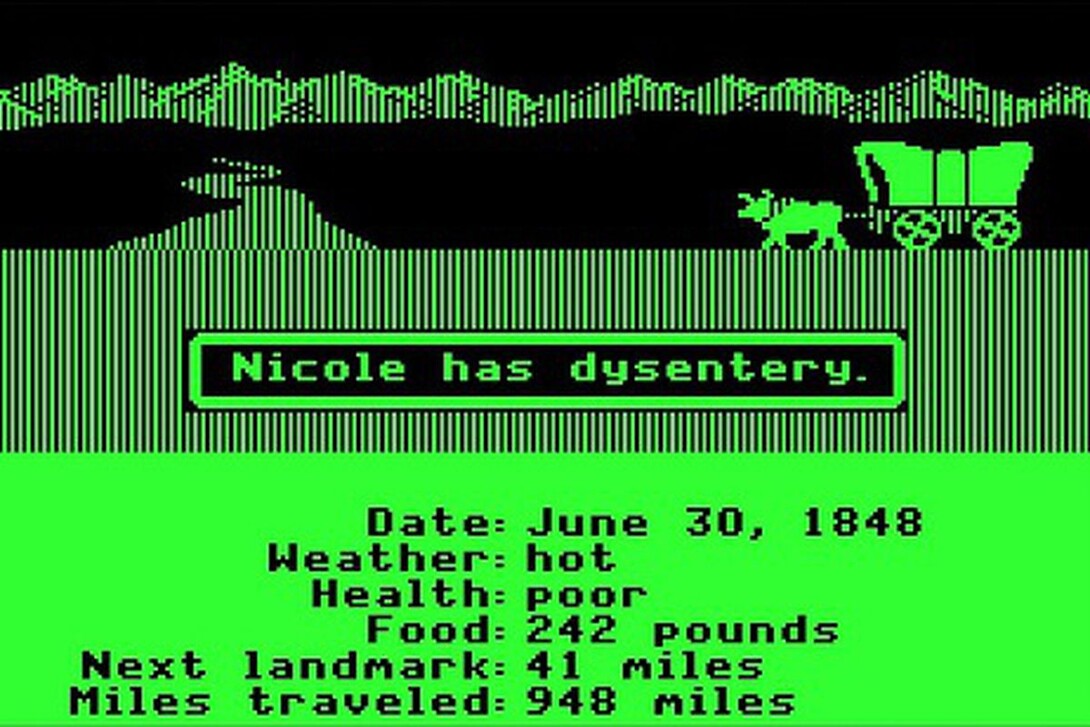

Enjoyed by millions since its release in 1971, the text-based strategy game allows players to lead a wagon train across the 2,170-mile Oregon Trail route from Independence, Missouri, to Oregon City, Oregon. Much like a real wagon captain in the 1850s, players encounter a litany of perilous challenges — river crossing and critter encounters to supply shortages and disease outbreaks. Make the wrong decision and a hardship leads to a delay, damage or death (including the infamous dread of dysentery).

“I grew up playing the original green and black version on school computers,” Huettl said. “It’s nostalgic for me. It’s also problematic in the way it depicts Native people as threatening, encountered in the distance or saying things like, ‘You are not welcome here,’ in broken English.

“Natives were this scary force that lurked at the edges of the game — counted alongside dangers like rattlesnakes and dysentery.”

Lessons in history

For many Indigenous people like Huettl (who is from Wisconsin and is a Lac Courte Oreilles Ojibwe descendant), encountering negative depictions of Natives is nothing unusual.

“Particularly in popular culture there are very few positive or accurate representations of Natives,” Huettl said. “You don’t really think about it as a kid, but growing up Natives are constantly hit with negative connotations of our families. Too often, these depictions leave a lasting impact on self-worth and the value of our heritage.”

The anti-Native messaging is also reinforced within society itself. From her youth, Huettl experienced the Wisconsin Walleye War, a late 20th-century protest of Ojibwe hunting and fishing rights. The conflict sparked strong protests by sports fishermen and resort owners who objected to tribal members being allowed to spearfish walleye during spawning season.

“It was an ugly conflict that eventually ended with the courts siding with tribal governments and existing treaties,” Huettl said. “But, it forever connected some of my earliest memories of being Indigenous to anti-Native sentiments.”

And while she made a stand in fourth grade, crafting (with help from her grandfather) a wigwam rather than a settler’s log cabin as part of a state history lesson, Huettl didn’t enter college planning to pursue a Native-centered career.

“I went into college thinking I was going to study Chaucer and old English literature,” Huettl said. “But, that changed. The more I learned, the more frustrated I became about Native history, literature and science being erased in dominant culture.”

Turning point

To help pay for college, Huettl started working at Old World Wisconsin, an open-air museum that depicts the daily life of 19th-century settlers. As the primary focus was on immigration, Huettl grew increasingly uneasy that the stories being told failed to provide a Native representation.

She found a growing desire to tell the stories of tribes in the state. The Oneida, who were forced to relocate from New York to Wisconsin in the early 1800s. The Dakota who once called Wisconsin home, but now are based in South Dakota. The Ojibwe, Menominee, Potawatomi and Ho-Chunk (Winnebago) who all saw their resource-rich land diminished to a handful of reservations through broken treaties and non-Native encroachment.

“The lack of representation of Indigenous people is what made me change my career path from Chaucer to Ojibwe,” Huettl said. “My grandpa in particular was very supportive of this change. He wanted me to find a way to tell Ojibwe history and rethink how it mixes with traditional American history.”

When she discussed a desire to study from Native American perspectives, a faculty adviser cautioned against the idea, citing a lack of Indigenous sources. Huettl forged on with the transition presenting itself official in her honors thesis, a literature review on Kiowa writer N. Scott Momaday.

With her first real “adventure” into Native history under her belt, Huettl expanded the study at the University of Oklahoma and University of Nevada, Las Vegas, earning masters and doctoral degrees, respectively. She joined faculty at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln in 2016 and is now an assistant professor of history and ethnic studies.

Along the way, Huettl discovered that the faculty adviser was not entirely incorrect regarding Native voices in historical sources.

“There’s not a lot of data out there because — and this is not a surprise — Native people don’t just want to give out their information to anyone,” Huettl said. “But, if you are patient and ask the right questions to the right people, the source material exists.

“You just have to learn how to read colonial archives through Indigenous perspectives.”

Redirecting the Oregon Trail

Gameloft, a France-based video game publisher, has partnered with Apple Arcade to update and deliver Oregon Trail to the past, present and future generations of players. A large part of that work included a push to eliminate historical inaccuracies and stereotypes regarding Native American people.

Realizing the need for expertise, Jarrad Trudgen, a creative director at Gameloft Brisbane, brought in three Indigenous historians to assist with the project. That group included Huettl, William Bauer from UNLV and Katrina Philips of Macalester College.

“The design team was well aware that the game, as it existed in the past, had problematic representations of Indigenous peoples,” Huettl said. “They wanted to do better with this update and they asked us to help eliminate the clichés and expand the historical accuracies.”

The team’s work included gathering historical data to create more appropriate names for game characters, expand roles for Native Americans and people of color, and more accurate depictions of Indigenous clothing, culture and adoption of modern technology (including their use of rifles rather than bows and arrows).

Each of the revisions is reflected in the game as it was released in the Apple Arcade earlier this year. It also includes a mini-game that includes a Pawnee family impacted by disease and moving to a winter camp and an acknowledgement of the many impacts westward expansion had on Indigenous peoples. The acknowledgement, which appears at the start of the game, was written by Huettl.

“The game no longer shies away from those difficult aspects of history,” Huettl said. “It’s not perfect, but this version of Oregon Trail is a game that is deliberately designed to depict Native people fully as human beings.

“There’s more to do, but I’m very proud of the work.”

In a statement about the work, the university’s Anti-Racism Journey co-leaders said Huettl’s work on the app project is amazing and necessary.

“Indigenous historians, as well as indigenist historians, must be the storytellers of any video-gamed representations and depictions of the Original Peoples of the land now known as the United States of America,” the co-leaders wrote. “In that way, the stories told about the Oregon Trail will be rich with complexity and authentic representations instead of the stereotypes and caricatures that typically misrepresent Native Americans.”

Looking ahead

Through the Gameloft project, Huettl has continued to move forward with her own scholarship and teaching. Her first book project, “Our Lands and Our People: Ojibwe Peoplehood on the North American West, 1854-1954,” is nearing completion and being considered for publication.

The book focuses on what is widely considered to be a period of decline in Native American history. It is an era that follows impacts of the Oregon Trail and at the height of American expansion. During these years, tribes continue to be removed from their lands, Native children are being sent to boarding schools, and laws are in place to halt Natives from practicing their religion.

“It looks at all of this from the Ojibwe/Anishinaabe perspective and how they saw a way to maintain sovereignty and their relationship to the land during this low point in Native history,” Huettl said. “Ultimately, my hope is that this book reaches Anishinaabe audiences and can be a meaningful resource on the history of this period.”

Huettl also continues to work with Gameloft on updates and expansions to the Oregon Trail game. A pending addition features a mini-game about the 1851 Horse Creek Treaty, a document that confirmed Indigenous nations’ rights to the northern Great Plains. Provisions also included an agreement that guaranteed safe passage for settlers along the Oregon Trail.

“It’s amazing that I’ve had this opportunity to improve the historical elements of a game that I spent hundreds of hours playing as a kid,” Huettl said. “It’s the most fun I’ve had with my research. And, it’s exciting professionally because it will reach thousands more than any book I can write, helping further understanding of Native American cultures and histories.”

Editor’s Note — If readers are interested in exploring more Native American-focused games, Huettl recommends “When Rivers Were Trails,” an Anishinaabe-related, point-and-click adventure about the impact of colonization on Indigenous communities in the 1890s. It was developed via a collaboration with the Indian Land Tenure Foundation and Michigan State University’s Games for Entertainment and Learning Lab. Learn more about the game here.