Plastics have revolutionized modern life, from containers that store food and water to medical devices that save lives.

But their tiniest byproducts — micro- and nanoscale particles released into the environment — are raising concerns about long-term health and ecological impacts.

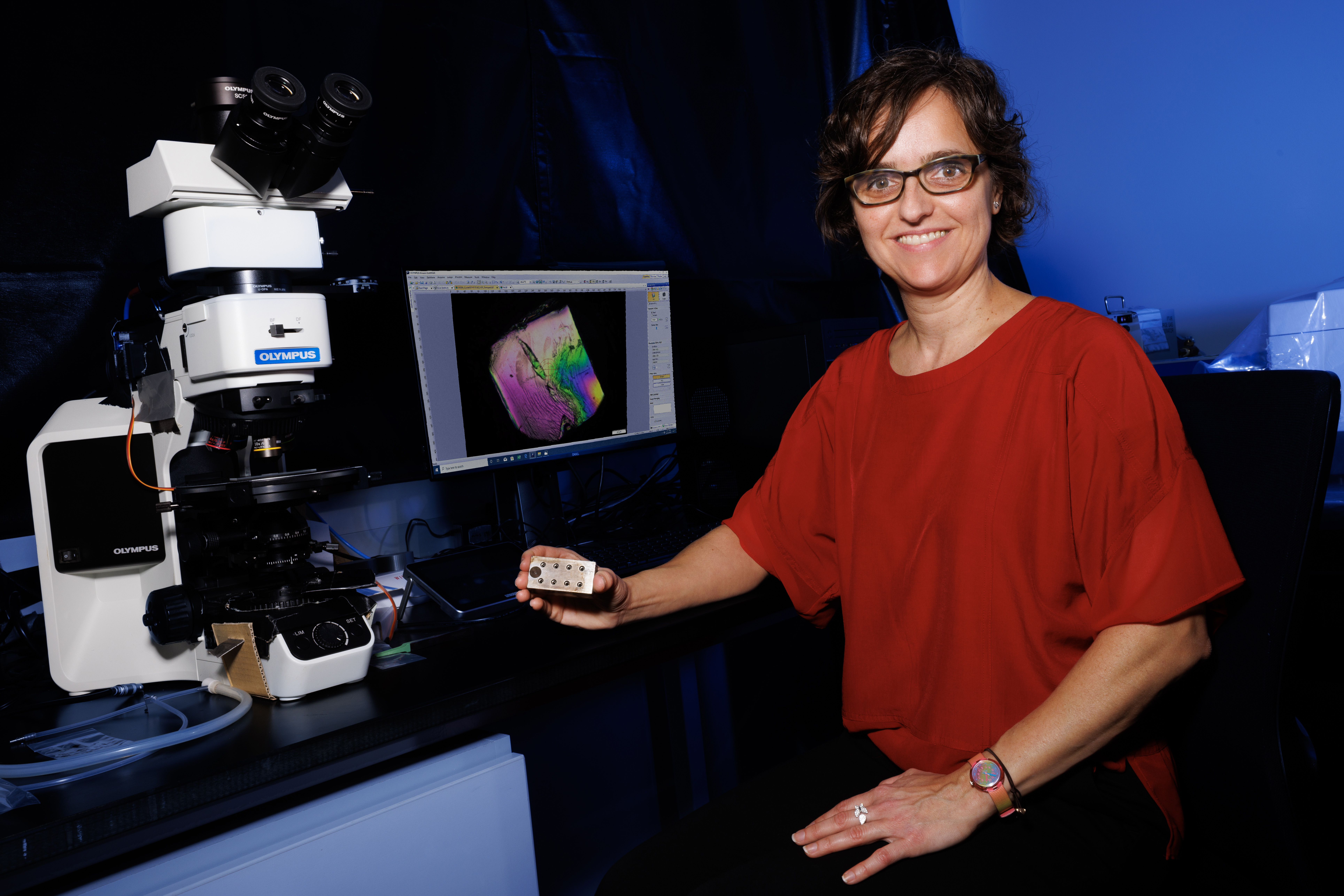

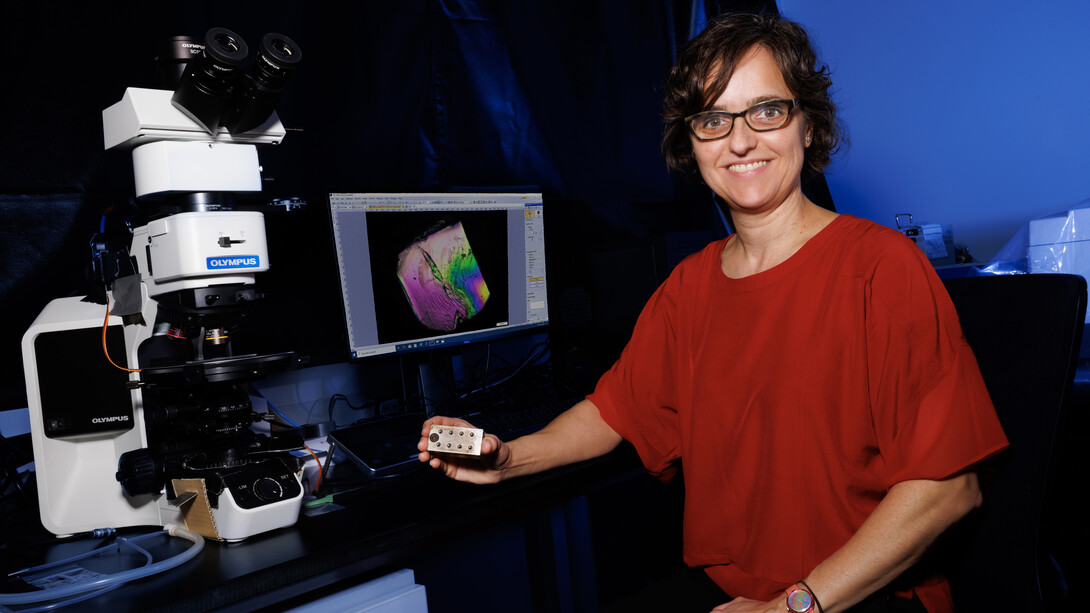

With a $739,205 Faculty Early Career Development Program grant from the National Science Foundation, University of Nebraska–Lincoln engineer Lucia Fernandez-Ballester is working to uncover how these particles are released and, ultimately, design safer plastic materials.

The five-year study aims to break down polymer manufacturing processes to better understand how micro- and nanoplastics enter the environment. It is a pioneering approach to a burgeoning problem.

“This field is in its infancy,” said Fernandez-Ballester, assistant professor of mechanical and materials engineering. “The problem is that there’s not much information about the health and environmental impacts and about what factors determine the release of those plastics.

“Because very subtle changes in a polymer can have a big impact, and there are many factors that can change, it can become convoluted. That is the research side of my CAREER project — allowing for rational design of polymers and processing to get the desired mechanical properties or performance and to minimize, or control, the release of micro- and nanoplastics.”

Polymers are large molecules made by chemically bonding a series of building blocks. These small, repeating units — known as monomers — are linked together in chains that combine to make materials. The substances can be produced by both natural processes (like those that create proteins, DNA and cellulose) and artificial processes (like those that produce rubbers and plastics).

In the past decade, concern has risen over the release of plastic particles and the link to health issues in humans and animals. Three years ago, a World Health Organization report recommended limiting exposure to micro- and nanoplastics.

In 2023, a Nebraska research team that included Fernandez-Ballester found that microwaving plastic baby food containers can release huge numbers of plastic particles — more than 2 billion nanoplastics and 4 million microplastics — for every square centimeter of the container. The study, reported in the journal Environmental Science and Technology, showed that only 23% of kidney cells exposed to the highest concentrations survived after two days of exposure. That mortality rate was much higher than in previous studies.

Fernandez-Ballester is using that research as a foundation for the work on her NSF project.

“We saw that there were micro- and nanoplastics being released from the products our children were using in daycare settings — toys, bottles, food containers,” she said. “Our research was very broad, but not in depth (in that area), so I decided to take a closer look into the well-defined materials and processes for making those materials, which is really my area of expertise.”

The tweaking of the smallest details of a polymer, Fernandez-Ballester said, can sometimes have a dramatic impact on the performance of the final product.

Understanding those little changes isn’t easily accomplished but can be important to better control how the polymers perform and degrade.

“Plastics have had a real big role in improving our quality of life. We need to use them, but we have to be very mindful of their impact,” Fernandez-Ballester said. “My project takes into account the entire life cycle of the polymers and to figure out the fundamentals of the polymer itself — ‘What is it about how we process them that affects how those plastics are released?’ — so that we can then make informed decisions about manufacturing and make safer materials.”

Educational outreach is part of every CAREER award, and Fernandez-Ballester is looking at working with elementary school teachers, helping them become more familiar with research and science and more confident in bringing STEM activities into their classrooms.

“The polymers, sustainability, recycling — those are good topics for those classrooms, and they are an offshoot of the work I’m doing,” Fernandez-Ballester said.

“This whole (CAREER) project, from the research to the outreach, is about making our world a safer, better place for ourselves and the coming generations.”