Four years ago, amid the COVID-19 lockdown and the constraints of social distancing, a collaborative research team sent observers around the country to study the factors that create long wait times at polling places and voting centers.

Data collected in that election helped the Engineering for Democracy Institute team — including Nebraska Engineering’s Jennifer Lather — make recommendations to help election administrators and officials make data-based decisions and put more flexibility in voting processes.

Those decisions might even be in place when another large voter turnout is expected for the 2024 election on Nov. 5.

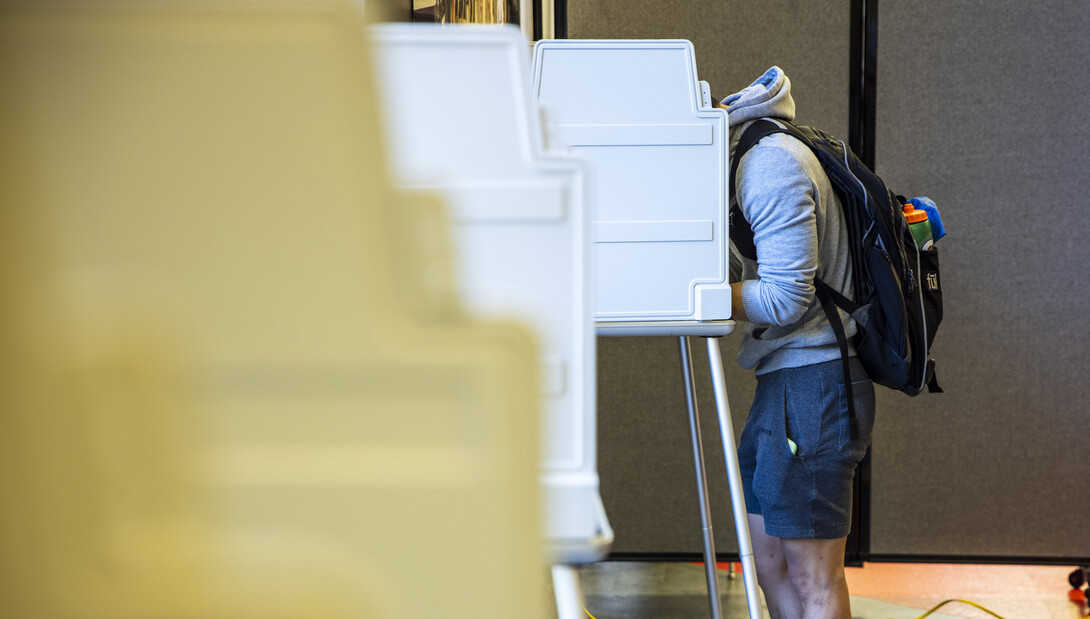

“There’s a lot at stake for voters and election officials in this period," said Lather, assistant professor in the Durham School of Architectural Engineering and Construction. "They want the experience to be one where (voters) feel they are able to … vote and that everyone goes through the process and is satisfied with it."

“We need to plan for problems that might occur — from congestion at check-in to long lines to maintaining confidentiality at balloting stations — so that all registered voters can exercise their rights on Election Day. Our work is helping to understand how to manage (those) times.”

Among the biggest obstacles voters faced in November 2020 was long wait times at voting sites due to about two-thirds of eligible voters participating, the largest turnout for a presidential election since 1900.

In 2020, about 37% of voters across the nation said they waited 10 or more minutes before filling out their ballot, according to research by the Pew Research Center, with 17% waiting more than 30 minutes, and 6% more than an hour. Of those who experienced the longest wait times, more than half said long lines from the high turnout were mostly the reason.

Both Engineering for Democracy Institute researchers and election officials are concerned about the effects long wait times might have on current and future turnouts and that they can erode voters’ confidence in the election process, Lather said.

“We do know that if it takes too long to vote, if there are long lines, people will leave, and it’s important that we make sure people don’t have to experience as much of that as possible,” Lather said. “This can, possibly, lead to them not even voting in the next (election) cycle.”

Learning which times are most likely to have more people vote and what causes “bottlenecks” can help administrators make decisions about managing election processes.

A paper co-authored by Lather and published by the Journal of Simulation in 2022 examined multiple approaches to polling site layouts. The results indicated that layout methods can have a direct impact on the throughput time — how long it takes to get an individual voter through the voting process. The study showed that, under certain conditions, sites with voting stations aligned around the perimeter of the polling location provided lower averages for times voters spent there.

Lather said elements in play in 2020 — including additional precautions in space requirements during COVID-19 changing the physical layouts of polling places — also helped researchers understand important factors in the choice of polling places.

Certain buildings and building types — such as nursing facilities, churches, community centers and schools — have been typical voting locations for decades. However, many polling locations were changed in 2020 to allow more people in those spaces while maintaining the integrity of the voting process.

“We can look at past numbers and then work backward when we think about what it will be like when voters come to the polls, how many more ballot stations do we need, what to do when there’s more people than we expect, and then run through all the possible scenarios before we choose the locations,” Lather said.

By inserting flexibility — such as preparing for various turnout rates — into systems at work on Election Day, Lather said, both election officials and researchers are hopeful the 2024 election will see a decrease in both the size of and number of long lines of voters waiting to cast their ballots.

“We're trying to create a consistent process that's safe, secure, and allows for everyone to feel like their privacy around how they vote is maintained," Lather said. "What our work has helped us do is go from traditional rules of thumb used when we’re planning and add a little more data and nuance so we’re ready for changes on Election Day.”

Share

News Release Contact(s)

Related Links

Tags

High Resolution Photos

HIGH RESOLUTION PHOTOS