Unpredictable cold spells can spell disaster for farmers, especially when it comes to sensitive crops like sorghum. But researchers at the Center for Plant Science Innovation at the University of Nebraska–Lincoln are on a mission to give this grain a winter coat, and it all boils down to understanding its daily rhythm.

“Sorghum is a fantastic crop — sustainable, low-input and perfect for biofuel production,” said Rebecca Roston, Ralph and Alice Raikes Chair of Plant Sciences and associate professor of biochemistry. “But it dies when the temperature drops, limiting where it can thrive.”

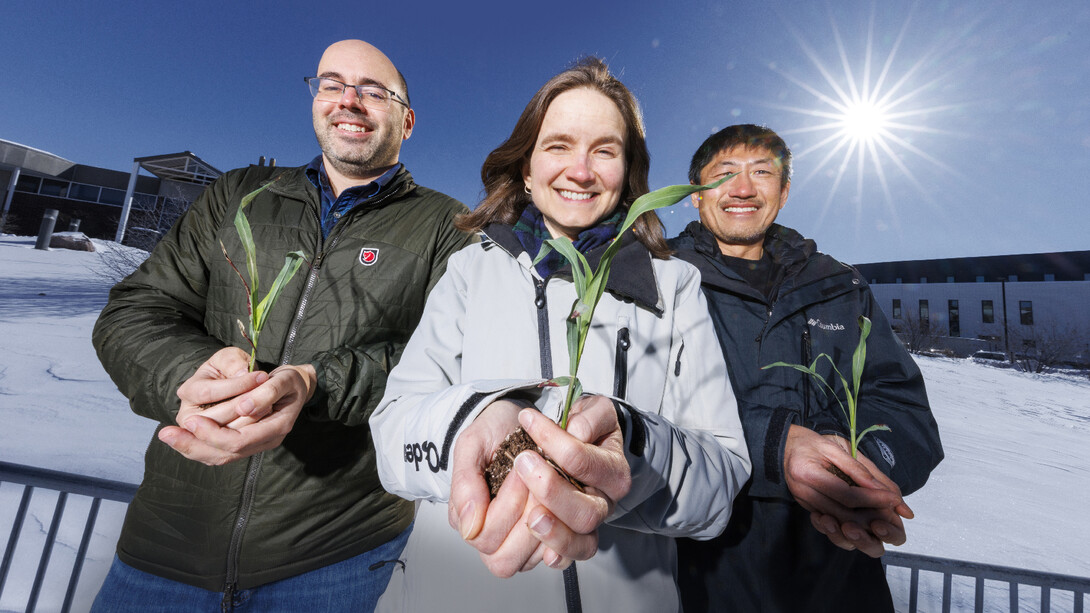

Roston is leading a team that recently received a $1.8 million grant from the National Science Foundation to pursue an innovative strategy for enhancing the cold tolerance of sorghum — and eventually, its close relative, corn. By comparing the internal clock of sorghum to that of cold-tolerant foxtail millet — which is, like sorghum, a member of the Panicoid grass subfamily — the team aims to learn how to harness sorghum’s circadian rhythm to increase its resilience to low temperatures.

This approach could be a game-changer for farmers, paving the way for a future where food security is not threatened by a surprise frost and growth occurs earlier, allowing crops to capture more of the total sunlight that falls on a field throughout the year. The key is tapping into the power of timing: Roston’s team has observed that the levels of sorghum’s key defenses against cold — certain fats and chemicals — fluctuate throughout the day. The goal is to use these fluctuations advantageously to boost sorghum’s tolerance when Mother Nature throws a cold fit.

“Think of it like taking your vitamins at the right time for maximum effect,” Roston said. “By understanding sorghum’s natural rhythm and comparing it to its more cold-tolerant relative foxtail millet, we can design strategies to enhance sorghum’s cold-fighting machinery at precisely the moment it needs it most.”

The team also includes James Schnable, Nebraska Corn Checkoff Presidential Chair and Professor of Agronomy and Horticulture; Toshihiro Obata, associate professor of biochemistry; and Frank Harmon, adjunct associate professor of plant and microbial biology at the University of California, Berkeley.

To this point, a major hurdle to engineering cold-tolerant sorghum has been the reduced general fitness that comes with it: The changes that fortify the crop against cold also impair its performance under normal conditions. To overcome this, the team will investigate the rhythmic differences that enable foxtail millet to strike an effective balance between cold hardiness and general productivity.

“The powerful thing we have in looking at foxtail millet, which has been growing across the latitudes of the Earth for thousands of years, is that it’s had to handle this balancing act: How do I be prepared for the cold, but also be a very productive plant when it’s not cold so I can survive and propagate?” Schnable said.

“Rather than trying to figure this out from scratch, we can look at the solutions that natural and artificial selection have arrived upon for this very close relative of corn.”

The study is innovative for its exploration of cold tolerance in the context of plants’ daily rhythms. Scientists have long known that a large proportion of plant genes, and how those genes are regulated, change throughout the day. But there have not been large-scale efforts to learn how those fluctuations impact plant characteristics, a gap Schnable and Roston first noticed as they collaborated on a U.S. Department of Agriculture-funded study in 2017.

Their data set indicated that time of day was closely linked to how plants responded to cold stress. They also noticed that other research groups were reporting inconsistent findings, likely due to applying stresses to plants at different points in the day.

Those observations laid the groundwork for the current NSF project. Obata joined the team in 2021 to lend expertise in the daily cycle of soluble metabolism; Harmon contributes expertise in the diurnal cycles of plants.

To help students and the public better understand plant movement and cold tolerance, the team is partnering with experts at the University of Nebraska State Museum-Morrill Hall to develop an interactive exhibit showcasing the hidden world of plant rhythms. They will also collaboratively develop a traveling exhibit that takes plant science to rural schools in Nebraska.

The project is funded through NSF’s Plant Genome Research Program, which supports genome-scale research that addresses challenging questions of biological, societal and economic importance.